China has too many hands steering its maritime policy

Linda Jakobson says volatility is inevitable with each pushing their own agenda

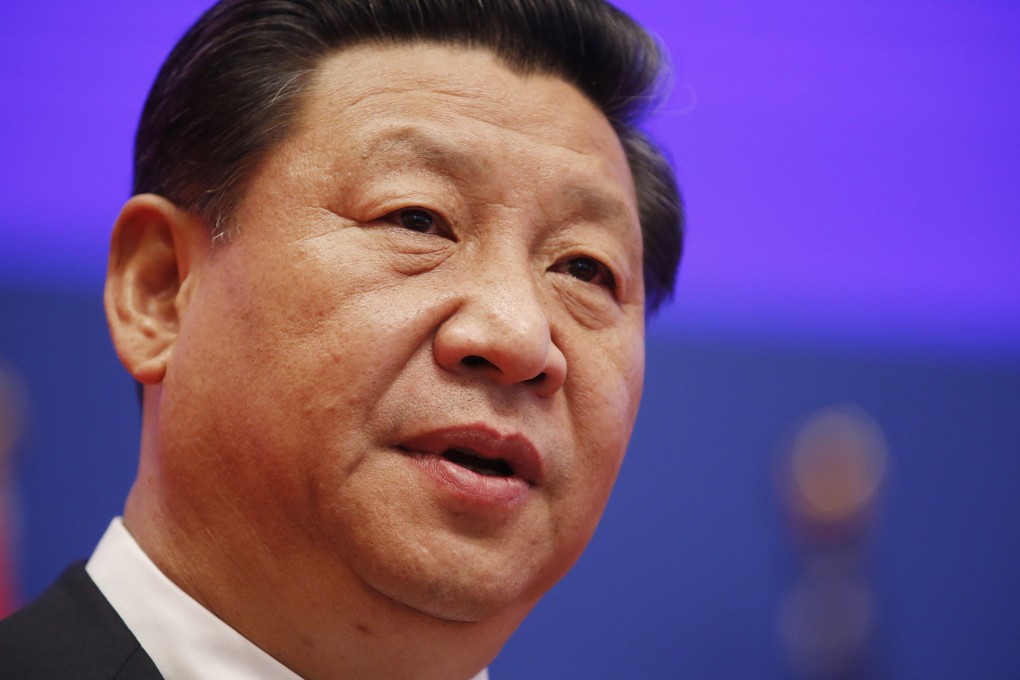

President Xi Jinping's recent speech on China's foreign policy offered a bit of something to everyone. He lent credence to those who, of late, have started to view Beijing's approach to its neighbourhood as more conciliatory.

Between the lines, one could sense a tacit acknowledgement by Xi that China's assertive maritime actions have been detrimental to its international standing. At the same time, those who remain sceptical of any change in Beijing's approach can point to Xi's message that China will resolutely defend sovereignty and its maritime rights.

The speech was similar in tone and substance to the one Xi gave a year ago about China's peripheral diplomacy. Xi said neighbours are to be treated "as friends and partners, to make them feel safe and to help them develop". No doubt Japan, the Philippines and Vietnam, the three neighbouring countries that have borne the brunt of China's provocative maritime behaviour, wonder how China would treat non-friends.

Xi's statements are intentionally ambiguous. He wants to assure neighbours, others in the region and the US in particular, that the "big guy" - as he called China in Australia last month - is not a bad guy. Why? Because to continue to grow more powerful, China needs the outside world. But at the same time, Xi wants outsiders to realise - and accept as inevitable - that big guys do things their own way.

Chinese leaders rely on vaguely formulated guidelines - so vague that a guideline can be used to justify an array of sometimes competing policy objectives.

Take, for example, the way Xi has outlined the direction in which China should pursue its maritime interests: China should "plan as a whole the two overall situations of maintaining stability and safeguarding rights". Previously, during the Hu Jintao era, preserving stability was paramount. Xi has elevated safeguarding rights to an equally important position, giving rise to a feverish "rights consciousness" that fits well with the prevailing nationalist undercurrents in China.