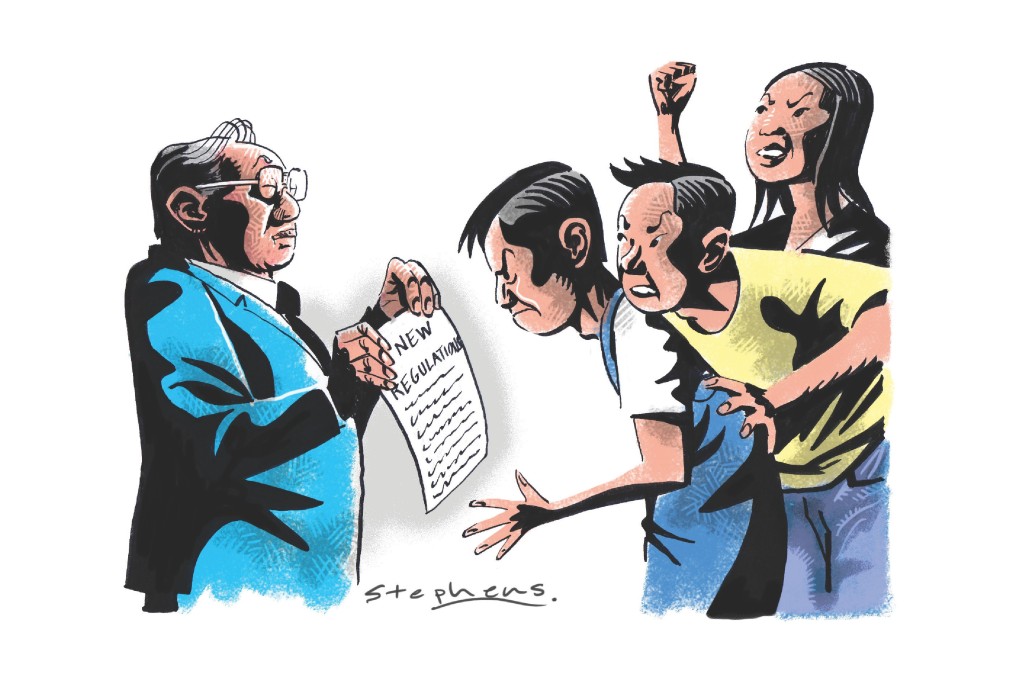

China's new collective bargaining rule is too weak to ease labour conflicts

Aaron Halegua says Guangdong's failure to enact a strict regulation requiring employers to negotiate with disgruntled workers is a missed opportunity to stem the rising number of strikes

Strikes in China are on the rise: 2014 witnessed over 1,378, double the number in 2013. This surge intensified in the run-up to the Lunar New Year. Guangdong is the hub of both export manufacturing and labour unrest. The strikes there have been increasingly well coordinated and growing in size - nearly 40,000 workers at a Nike footwear supplier last year, another 3,000 workers at a Hewlett-Packard subsidiary last month.

China's strikes are unique not only because of their frequency, but also their form. In the West, strikes tend to occur after a period of collective bargaining, usually as a last resort. In China, workers' opening volley is often a strike. This is because employers are rarely motivated to negotiate until there is an immediate economic reason to do so. Further, without a functioning trade union, no practical mechanism exists to notify employers when workers are discontented and contemplating action.

But why does this difference matter? Although we read that many of these worker actions have resulted in higher wages or other benefits for employees, these strikes with "Chinese characteristics" also have very real costs to employers, the government and, most importantly, the strike leaders who are routinely fired and sometimes jailed.

Guangdong authorities recently adopted a regulation to foster collective bargaining and reduce strikes. Unfortunately, this effort is unlikely to succeed, and the pattern of strikes and repression can be expected to continue.

In practice, Chinese law affords striking workers little protection. In the Hewlett-Packard case, the worker who collected 4,400 employee signatures opposing a restructuring decision was fired shortly after the strike began. Fired strikers may turn to the courts to contest their termination, but they virtually never win.

Strike leaders face even worse consequences than loss of their jobs. They are often "blacklisted" and unable to find work elsewhere. Moreover, workers and advocates involved in organising a strike have been interrogated, beaten or detained by police, and sometimes charged with the nebulous crime of "disturbing public order". Some workers have even been convicted and served prison terms.

Workers are not the only ones burdened by China's unique labour relations system. The Nike supplier in Guangdong said the direct cost of the 40,000-worker strike last spring was US$27 million. Constantly calling out the riot police is also not cheap for local governments. Plus, strikes are problematic for officials obsessed with maintaining social stability.