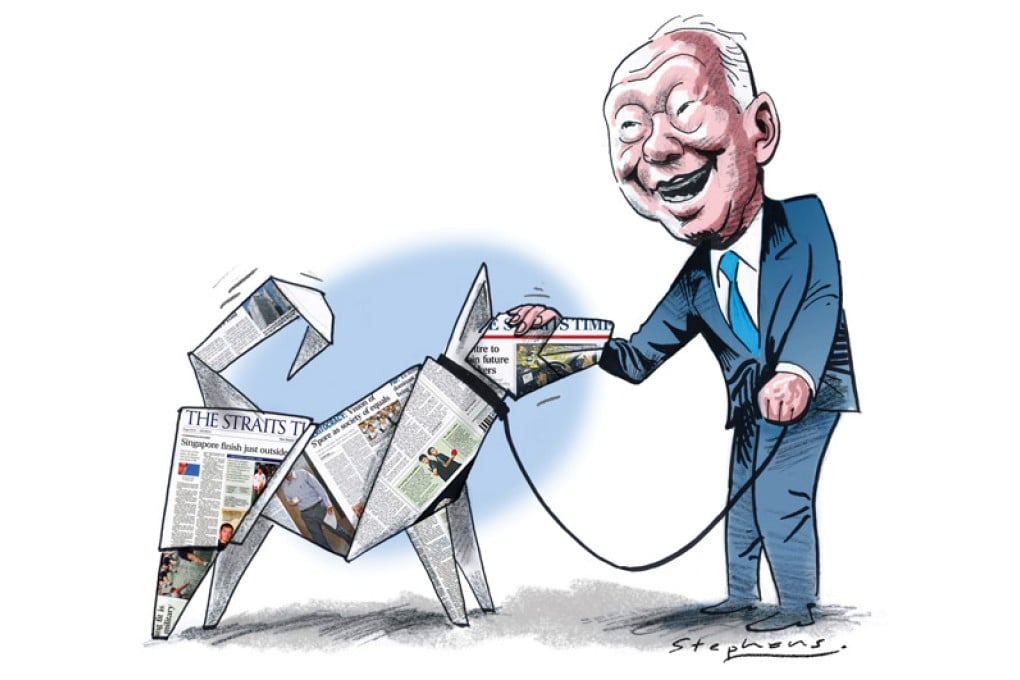

Under Lee Kuan Yew, the press was only as free as it needed to be to serve Singapore

Cheong Yip Seng tells how Lee Kuan Yew, who saw the press as subordinate to the nation's needs, made sure that only he and his government could set the agenda for Singapore

One November evening in 1999, Lee Kuan Yew telephoned: He was troubled by a new information phenomenon, which was threatening to overwhelm the traditional media industry. In America, the markets were rapidly coming to the conclusion that there was no future in print newspapers, whose eyeballs were migrating to cyberspace.

How would this information revolution impact the Singapore media? He was anxious to find a response that would enable the mainstream media to keep its eyeballs. He wanted us at Singapore Press Holdings to think about the way forward.

For him, the media was one of three institutions in Singapore he told an aide he needed to control in order to govern effectively. The other two were the Treasury and the armed forces.

His relations with the media had been rocky at the start of his political career. While he was in the opposition, not everyone in the press had sympathy for his political goals. The Malaysian Malay media, which could then circulate in Singapore, was hostile.

My first editor-in-chief, Leslie Hoffman, had a furious row with him over press freedom that blazed across the front pages of The Straits Times, and went all the way to the International Press Institute (IPI) annual assembly in 1959 in Berlin.

Once in office, Lee set out to change the rules of the game: he and his government, not the press, would set the agenda for the country. They wanted command of the national narrative.