Zhu Rongji's light touch is sorely missing in today's China

Tom Plate says China today could do with the foresight and calm self-confidence of a Zhu Rongji

Because we're human, we sometimes imagine nations as human beings - and babble on about their personality failures as if indulging in serious psycho-political analysis. We envision them as human-like, and declaim their boldness or weakness, or whatever, as if they were a singular personality.

Take the United States, for example - it's an ongoing, semi-functional jumble of competing forces, interests and partisanships that roil above and below constitutionally entrenched layers of competing government authorities. And yet we will depict the America of today as no more complex than - say - Barack Obama without the Harry Truman.

Even though China has four times America's population, it draws comparable anthropomorphic caricature as well. And yet it is such an endlessly sprawling kaleidoscope of the rural and the urban, Confucian/capitalist, central-party/deeply engrained native culture that it's folly to try to sum it up in fewer than a few billion words and a thousand metaphors.

But that doesn't stop us, because when thinking of Beijing, the anthropomorphic feeling is especially pressing: you feel in your heart that some important dimension in its current political personality is missing.

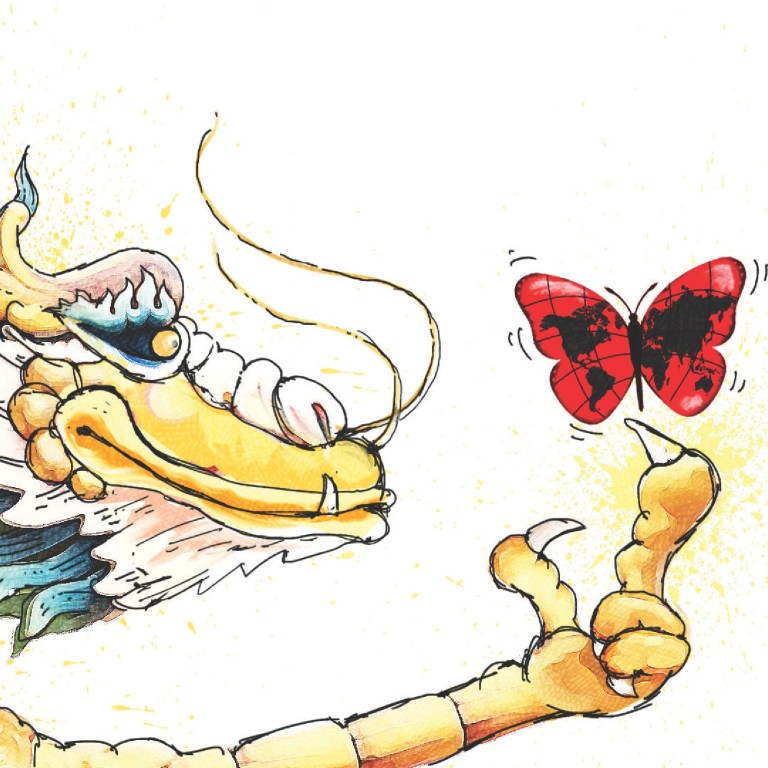

It is just a feeling, not a Princeton PhD thesis. Yes, China is not just emerging, it is emergent; it is no longer weak, and its diplomacy is starting to flex as muscularly as the well-photographed exercises of the People's Liberation Army. And, no question, even with the economy cooling, it is already a powerhouse. We all get this.

But, at the same time, we have the sense of an absent dimension and we glance back in time for something, or someone, to fill in the blank. No, it's not Mao Zedong ; the last thing we'd long for is a neo-Maoist figure; Deng Xiaoping was fine, but that's not it. And the current president, Xi Jinping , has been providing strong direction and making tough decisions - generally getting good marks from many international as well as domestic observers.

Still, something is missing - a top-level political personality who listens carefully, with a sense of subtlety and nuance, with placid self-confidence; even the ability to take a blow or two and not get instantly psyched up for war; some supreme serenity, with a brain born for geopolitics.

Here's a hint: Who on the mainland recently has said anything like this - and obviously meant it? "What we want to do is to work for the people's welfare and build China into a strong and prosperous country with democracy and the rule of law. We absolutely won't engage in hegemony or power politics as some other countries do, as we've suffered enough from these. What good can come from bullying and oppressing others? We can become rich and strong through our own efforts, and we won't bully others."

Yes, this was said in June 2001 by the same man who in 1989 refused to unleash troops onto Shanghai's streets to smash demonstrations, as had been done in that other metropolis up north; who wasn't afraid to meet students; who guided China into the great globalised unknown of the World Trade Organisation, despite a million honest doubts back home; and who managed to settle down his fellow Politburo colleagues after the "accidental" US bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999 - just one month after his White House humiliation by Bill Clinton, who cravenly back-pedalled and reneged over his promises on the WTO.

Through all this, Zhu Rongji , then the fifth premier of China, now in retirement, kept China cool simply by keeping his own; by averting his eyes from the inevitable setback, no matter how bitter, and affixing them to where China needed to be 10, 20, 30 years down the road. He was then - and now - exactly what was - and is - needed: a visionary with foresight.

It is no doubt an extreme case of anthropomorphic romanticising to want to believe that a Zhu-type figure would handle "bratty" Hong Kong with the same tactical deftness and insight as Zhu himself did with those 1989 demonstrators in Shanghai. The strength of the light touch reflects the core of self-confidence that breeds flexibility.

So when, as many expect, Hong Kong's legislature later this week fails to pass the electoral overhaul package for the chief executive election of 2017, many also expect Beijing to turn predictably cold - and sullen - and somewhat forbidding. Or will it shock the world and offer an unexpected but utterly self-confident turn of warm understanding?

Some countries are grand but not great, others are great but not grand; the rare ones are both great and grand.

The late Noel Annan, a Cambridge don, was famously insistent that the legendary thinker Isaiah Berlin's relentless emphasis on the impact of leaders on history was tragically underappreciated, particularly by academics.

He once lampooned them this way: "Social scientists have depersonalised acres of human experience so that history resembles a ranch on which herds move, driven they know not why by impersonal forces, munching their way across the prairie."

Real life takes place on no such barren ranch but on vast windy steppes of difficult historical realities. The exceptional leader can prove a huge value-added force. As authors Orville Schell and John Delury put it in their deeply illuminating book , "Zhu ensured that China would enter the 21st century poised to advance ever more rapidly …"

China faces great historic challenges and decision-crossroads now. If only its complex political personality contained a visible dimension of the Zhu Rongji touch.