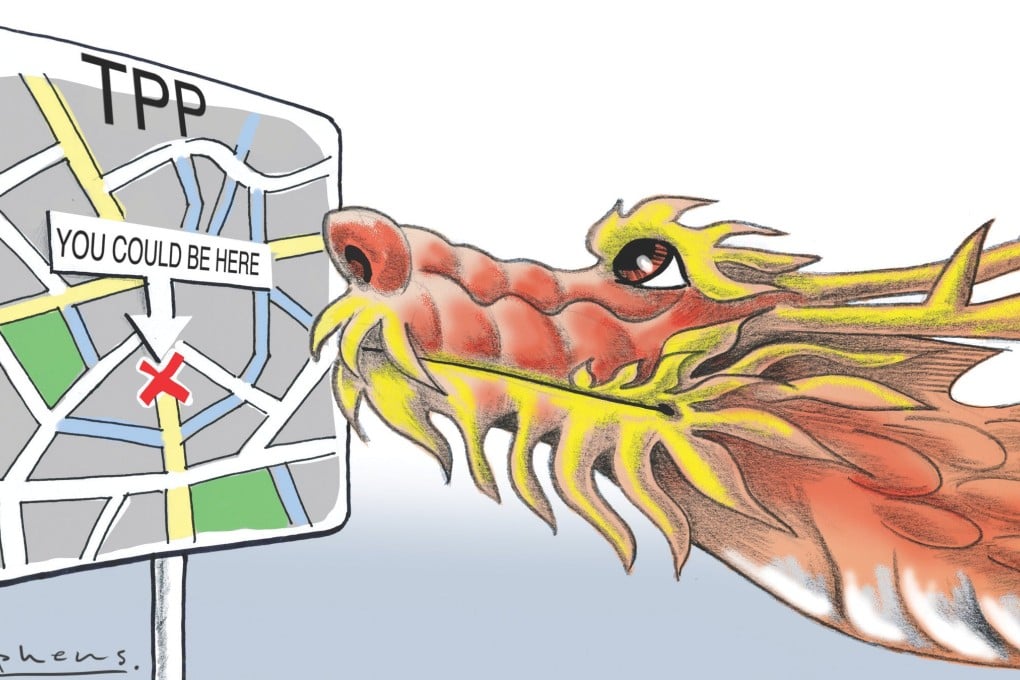

Why the Trans-Pacific Partnership deal is no threat to China

Stephen Nagy and Bryan Mercurio say the Trans-Pacific Partnership could hasten rules-based trade ties

Critics argue that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is a geopolitical tool and an ABC (anybody but China) trade agreement designed to contain a rising China. Others suggest it is not only the core pillar of the US "rebalance" to Asia but also the agreement that will set the rules for 21st-century trade. China itself has wavered in its views of the pact, from initial deep suspicion to a more nuanced view that acknowledges the benefits of the standards upheld in the agreement.

Seen from both a geopolitical and a trade law perspective, the TPP could set the stage for China's eventual inclusion through a socialisation process that avoids many of the pitfalls associated with its accession to the World Trade Organisation in 2001.

China could benefit by viewing the set of shared rules in the TPP as a way to push through long-overdue domestic changes

At the moment, the agreement's significant cuts to tariff rates on agricultural products, deep liberalisation of services and strong commitments on intellectual property rights, environment, labour and state-owned enterprises place serious barriers to China's immediate accession. Its economic slowdown and continued reliance on state-led economic solutions further dampen the prospects of entry.

Geopolitically, the TPP in the short-to-medium term weds the biggest and wealthiest consumer markets to the burgeoning manufacturing hubs in Southeast Asia. Countries such as Malaysia and especially Vietnam will be benefactors of large injections of foreign investment and preferential access for their goods to the large and wealthy middle-class populations in Japan, North America, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico and Chile. The mix of increased investment and exports should lead to greater levels of employment, increased exports and a healthier balance of trade terms.

If all goes to plan, these gains will outweigh the economic sacrifices made to join the trade pact by a significant margin. In due course, these gains will be powerful drivers for other regional countries - such as the Philippines and Indonesia - to make similar sacrifices, further linking economies in Southeast Asia to a trans-Pacific and American/Japanese-led grouping.

In a similar vein, the more advanced members of the TPP will receive greater and preferred access to the most dynamic region of the global economy, the Asia-Pacific. With young class-conscious consumers and rapidly growing middle classes, the region offers established brands an opportunity to entrench their names and win over the influential consumers of the future. Perhaps more importantly, the advanced economies can co-opt the emerging countries into their view of trade relations in the 21st century and lock in standards which could now only be negotiated on multilateral platforms.