How a little-known chapter in Sino-US cooperation may have helped save the planet

Tom Plate says talks between Li Zhaoxing and Condoleezza Rice 10 years ago, over who should be the next UN secretary general, paved the way for the Paris climate change agreement

But for this week, at least, we shelve apocalypse instincts and mull over a couple-reconciliation scenario. Our story will go back 10 years – and then intimately connect with the present – thanks to China-US get-togetherness. And to push the believability of the loving metaphor even further, the linkage involves the two most powerful members of the UN Security Council working with the UN secretary general in New York.

China to ratify Paris climate deal by September

The denouement came last week with the sweeping and promising Paris climate control protocol – a necessary first step in meeting the fearsome global-overheating challenge. Not only did 175-plus nations put pen to the protocol’s papyrus, but also – and more to the point – the Beijing-Washington odd couple led the political parade for the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, put together in Paris in December.

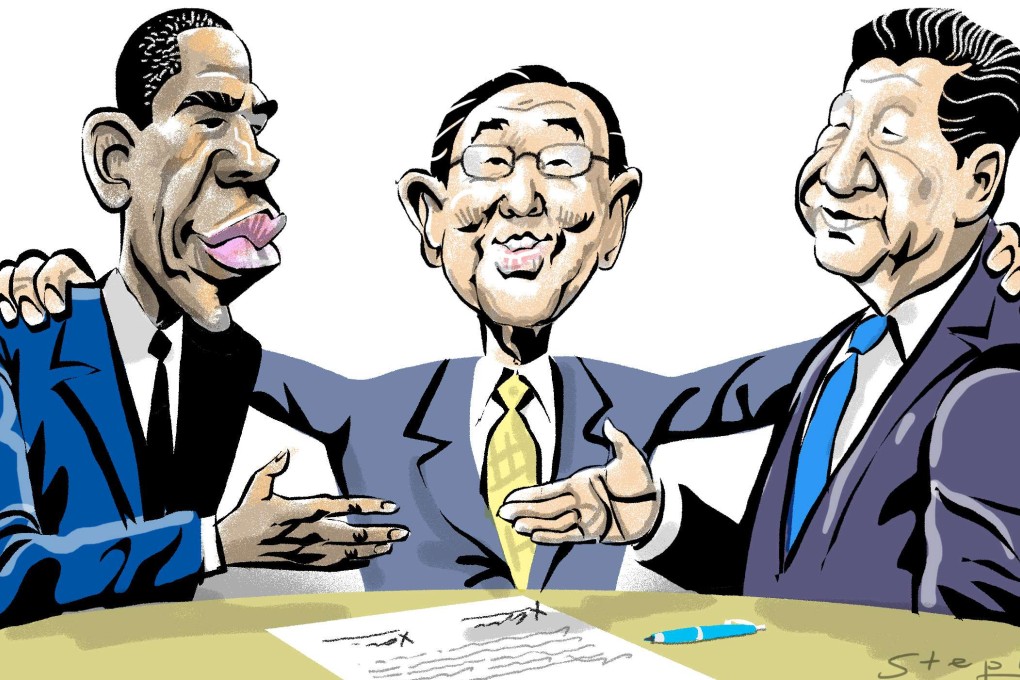

These titanic economies dump down on us 40 per cent of all global greenhouse gas emissions, for which both presidents Xi Jinping (習近平) and Barack Obama should be ashamed. In a sense, thankfully, they are, and last month signalled their intent to sign the Paris Accord, thus raising the UN-driven effort from the dead after the deeply unsettling climate-control negotiation collapse in Copenhagen in 2009.

This week, I vote for the former and ask you to offer a rare standing ovation for Xi and Obama.

The irrefutable fact of current geopolitics is that Chinese-US concordance offers the greatest potential transnational force for good (or evil) on this planet. When Beijing and Washington can get together, and then can get it together, the effect can be stunning. To add to the background of this much-headlined Paris accord, we recount a quiet event 10 years ago in New York about which much less is known. It was a meeting between Condoleezza Rice and Li Zhaoxing in the US ambassador’s suite at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, there to exchange views on the tricky selection of a successor to Kofi Annan.