To make peace with China, Abe should visit Nanjing for the 80th anniversary of the massacre

Jean-Pierre Lehmann says Japan must move beyond the indefensible amnesia of its aggression against its neighbours during the second world war. A visit by the Japanese prime minister to Nanjing would be a good start

Japan protests as China’s PLA Navy sails near disputed Diaoyu Islands in East China Sea

France and Germany were at war three times in the modern era: 1870-1871 (the Franco-Prussian war), 1914-1918, and in May 1940, when Nazi Germany invaded and occupied France until the liberation of Paris on August 25, 1944. Since then, the political leaders of France and Germany have made a solid and lasting peace. Germans accept their guilt and responsibility; no responsible German would deny that Germany was the aggressor and France the victim, there are no disputes whether over territory (for example, Alsace) or history.

China and Japan were also at war three times in the modern era: 1894-1895, 1931 (the invasion of Manchuria) and 1937-1945. In all three, Japan was the aggressor. While Japanese invaders murdered, massacred and enslaved Chinese civilians and raped tens of thousands of women, no Chinese military boot ever set foot on Japanese soil; there was no Chinese enslavement of Japanese labour, nor any Chinese mass rape of Japanese women.

Enough of all this second world war apology talk, young Japanese say

Yet, as highlighted in the excellent book by Ian Buruma, Wages of Guilt, memories of war in Germany and Japan differ radically. Whereas negationism of the Holocaust is a criminal offence in Germany, contemporary denial of atrocities committed by Japanese is widespread. No less a figure than Shintaro Ishihara, governor of Tokyo from 1999 to 2012, has repeatedly denied that the 1937 Nanking massacre – which witnessed the widespread slaughter and torture of Chinese civilians and the rape of Chinese women – occurred. Imagine the mayor of Berlin denying the existence of Auschwitz! Not only would he have been condemned by other German politicians, but the citizens of Berlin would have demonstrated in outrage. Not only were there no condemnations or demonstrations in Tokyo, but Ishihara was repeatedly re-elected.

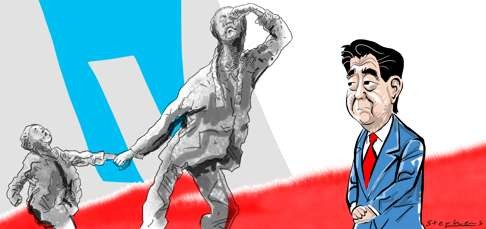

The visits by senior politicians to the Yasukuni Shrine, where “the souls” of a number of Japanese war criminals “repose”, including in 2013 by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe himself, demonstrate a combination of offensiveness and Japanese amnesia.

The real value of a Japanese apology

No German youth today would be ignorant of the crimes committed by her forebears during the Nazi period. This would not be true of Japanese youth or indeed members of Japanese generations born after the war. Often, Japanese acknowledge that they first learned of these atrocities while studying abroad. This is in good part because Japanese school history textbooks have been repeatedly revised and whitewashed. Pages dealing with the more barbaric sides of the war are deleted or downplayed.

Some claim that making peace with the Communist People’s Republic of China is different from the European situation. Communism, however, did not prevent then German chancellor Willy Brandt from visiting Communist Poland in 1970 and spontaneously falling on his knees at the Warsaw Ghetto Monument. Nor does it in any way absolve Japanese leaders, authorities and citizens from whitewashing history, engaging in negationism, or visiting Yasukuni.

It took decades and a lot of American pressure for Tokyo to own up, albeit ever so tepidly, to the Japanese enforced sexual enslavement of Korean women during the war

Furthermore, Japan’s tense/hostile relations are not only with “Communist” China, but characterise the relationship with all its major neighbours. Japan is engaged in territorial and historical disputes with South Korea, its former colony and a democracy. It took decades and a lot of American pressure for Tokyo to own up, albeit ever so tepidly, to the Japanese enforced sexual enslavement of Korean women during the war. At the ceremony attended by Abe and US President Barack Obama in Hiroshima, Abe did not mention, let alone atone for, the fact that some 50,000 Korean indentured labourers count prominently among the nuclear cataclysm’s innocent victims. As with China over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands, Japan has a vitriolic territorial dispute with Korea over the Dokdo/Takeshima islands.

Japan is also engaged in territorial disputes with its other former colony, Taiwan, and with Russia. Thus, while at the recent G7 summit at Ise-Shima, Abe managed to corral his co-summiteers into expressing criticism of China’s incursions in the South China Sea, no mention was made of Japan’s lingering post-war irredentism.

Why sorry is still the hardest word to say for Japan, 70 years after the second world war

Obama’s visit to Hiroshima must be followed up by action to reduce stockpile of nuclear weapons

Hirohito was emperor from 1926 to 1989, covering the years Japan invaded and carried out its atrocities in China. Though he was absolved by the American occupation command, historians have generally held that he should have assumed responsibility. In any case, whereas he paid official visits to the capitals of Japan’s erstwhile wartime enemies – the US, Britain and the Netherlands – he never paid a visit, official or unofficial, to any Asian country that Japanese troops had invaded; these include not only China and Korea, but also Mongolia, the then USSR, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Burma, Vietnam, Cambodia, Brunei, Laos, and Hong Kong. It is a bit as if, after the second world war, Germany had made peace with China, but not France, Poland, Britain and so on.

Thus, while Obama’s visit to Hiroshima was indeed historic, it was not a dramatic game changer. Since Japan’s surrender in 1945 and the end of the American occupation in 1952, Japan and the US have been allies; while in the 1980s there was some “trade friction”, there was never any risk that the relationship would deteriorate into conflict. Furthermore, though it would be a good idea, as some have suggested, for Abe to visit Pearl Harbour; that is not where the priority lies. The US and Japan are at peace.

Once friends, now foes? Unearthing the uneasy relationship between China and Japan

For the sake of peace between Japan and China, for the sake of peace in the Pacific and indeed for the world, the most urgent priority is for Tokyo to at last make proper amends. Next year will mark the 80th anniversary of the Nanking massacre. To that end, a visit by Abe to Nanjing (南京) would be an important step in the direction of rectifying the wrongs of the past and for building what has to be a durable peace between the two major Asian powers.

This would be far more important than an eventual visit by Abe to Pearl Harbour. This symbolic measure will help to sustain a peace between the US and Japan that already exists. Abe’s visit to Nanjing would actually help to make peace between two unreconciled former belligerents. In and of itself, it would not right all the wrongs of the past, but it would be a critical step in the right direction. It would also help raise Japan from the moral pits it has occupied in respect to Nanking and China since 1937 to higher and more respectable ground.

Jean-Pierre Lehmann is emeritus professor of international political economy at IMD, founder of The Evian Group, and visiting professor at the University of Hong Kong. An earlier version of this article was published by The Straits Times