How the West got China wrong

Stein Ringen says rather than see the superpower through the distorting lens of liberal standards, Western leaders should understand the dictatorship on its own terms and realise that their models cannot be applied to the nation’s unique system

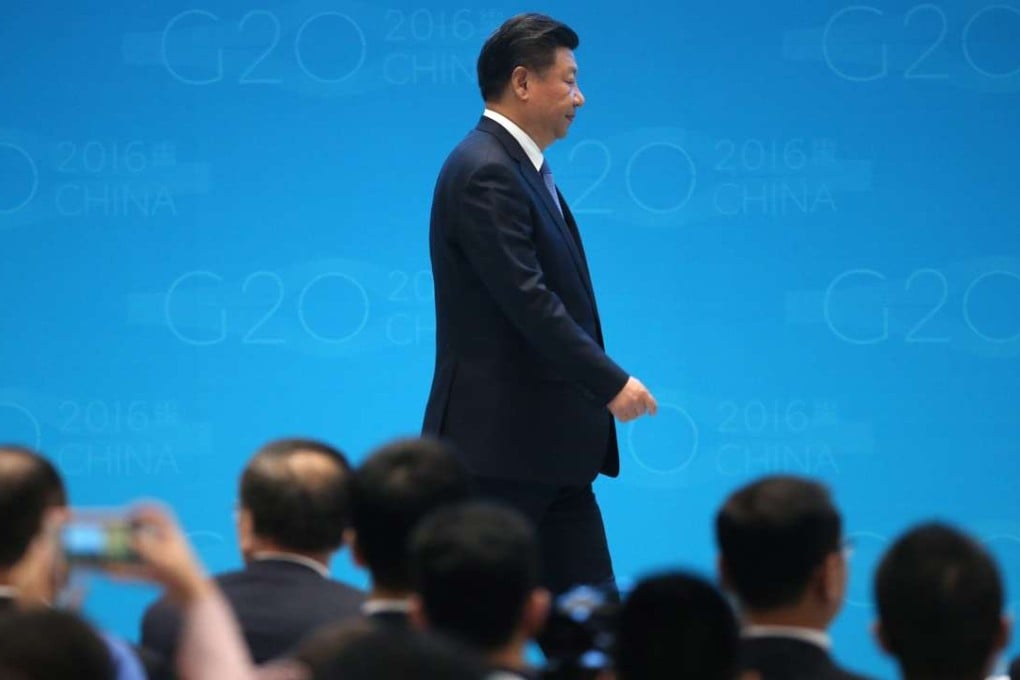

The Western misunderstanding of Communist China has been called “the liberal myth”. With our mindset and experience, it is almost impossible to grasp that a country can fail to open up politically when it opens up economically. “The more we bring China into the world,” said then president Bill Clinton, “the more the world will bring freedom to China.” We thought the new middle class would make itself a force for liberalisation. But, in the socialist market economy, it has instead aligned itself with the Communist Party. We thought the internet would forge opening up from below. But, behind the Great Firewall, it has instead become another instrument of control from above. Liberalisation has not happened, but we cling to the belief it will. When Xi Jinping (習近平) came to power in 2012, it was thought, with no evidence whatsoever, that the time had come for a new leadership of reform. What has followed is ever tighter dictatorship.

Xi Jinping faces his biggest political test

The Chinese model is unique. We get it wrong if we try to squeeze it into our own models. It needs to be understood on its own terms.

China has all but ended the charade of a peaceful rise

For those who deal with China from outside, there is a huge temptation to see it in a good light. It is a big power and economy with which we must get along. It is an ancient oriental culture which attracts fascination. The West is bedazzled by China’s mysticism and bigness. Henry Kissinger, for example, pays Beijing tribute with his romantic notion of the “civilisation state”. The academic literature on China is generally critical, but much of that criticism conforms in its way with the liberal myth. We observe the absence of the rule of law, but take that to be a pathology in a regime that could do better. We observe the censorship, the propaganda, the “thought-work” and the thuggish “stability maintenance”, and criticise the regime for its excesses. The abuse of the law and the courts and the brutal clampdown on any form of opposition are, however, not “mistakes” on the part of a confused regime. These practices are logical and necessary, given the regime as it is.

In the Chinese party-state, there is a supreme determination that trumps all others: stability, meaning the regime’s perpetuation of itself. The post-Mao rulers have had two strategies of self-preservation: the purchase of legitimacy and the exercise of control. During the past decades of rapid economic growth, they could rely on being rewarded for economic betterment. But mega growth is now over and people’s expectations are outrunning government delivery. The leaders are therefore shifting to relying more on controls. Behind Xi’s tightening of dictatorship lies a steely analysis of what is needed to avoid the disintegration that has befallen previous Leninist systems, primarily the Soviet Union.

A dispassionate analysis of today’s Chinese system is despondent. Not much, if anything, can be expected of reform for the better from within. However, the model is still, to some degree, in the balance, if only between harder and softer dictatorship. That difference matters enormously for the Chinese people and for the world.