Just how far can the new friendship between China and the Philippines go?

Donald Kirk says while Filipinos have good reason to strike a deal with the Chinese, a key question remains: can Beijing provide the military aid the US has been giving Manila, and at what price?

If his declarations are puzzling, however, they should not be all that hard to understand. Beneath the show of nationalist pride that Duterte is expressing lies a certain common sense. After all, is the US, despite its much publicised “pivot” to Asia, willing to risk an armed clash with China in the South China Sea?

US likely to increase patrols off disputed South China Sea islands after ‘pivot to Asia’ hits choppy waters

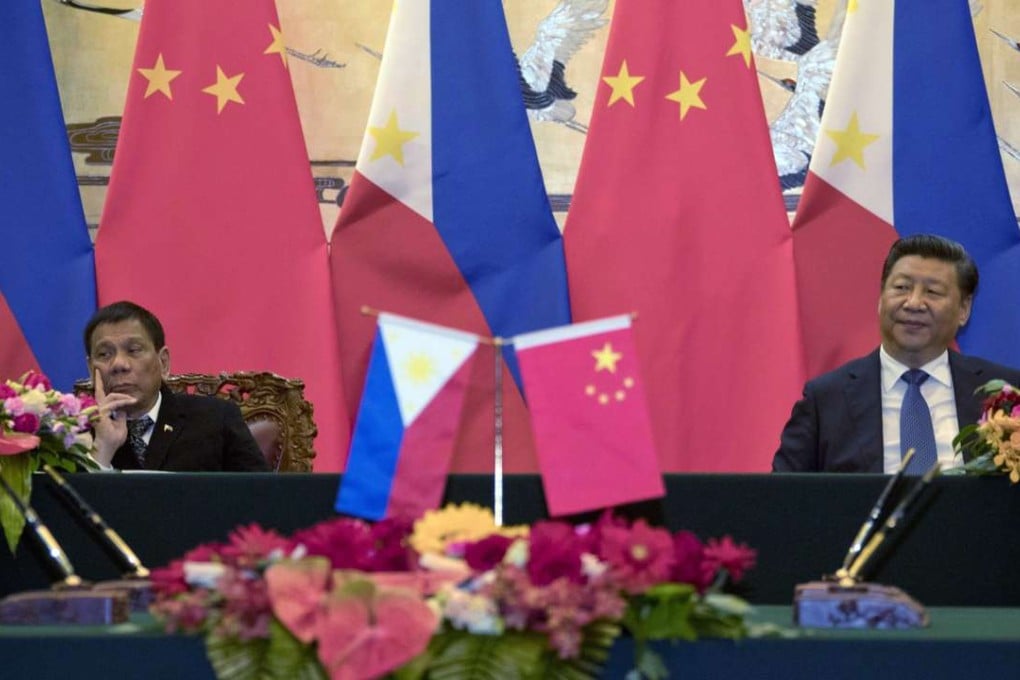

That ruling, however, was not so much a defeat for China, which had said the court had no jurisdiction, as a challenge to the Philippines and the US to enforce it. Nobody imagined that Duterte’s predecessor as president, Benigno Aquino, could do anything militarily, but what about the US, which vigorously supported the decision? Duterte, by siding with China during his recent visit to Beijing, including a summit with President Xi Jinping (習近平), left no doubt that the ruling had little meaning.

US Navy exercise in South China Sea is dangerous and provocative

The reality is simple. The US might periodically show its colours, but there’s no way it is going to go to war in the Spratlys on behalf of the Philippines or any of the other claimants, including Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei. Nor, for that matter, is the US remotely interested in battling the Chinese with regard to Scarborough shoal, the rocky outcrop within Philippine territorial waters.

The US might periodically show its colours, but there’s no way it is going to go to war in the Spratlys on behalf of the Philippines