Inexcusable delays are undermining trust in Hong Kong’s legal system

Grenville Cross calls for deadlines to be set and improved manpower allocation to speed things up, as public confidence in our institutions’ ability to deliver justice, once lost, may be hard to regain

“Delay in justice is injustice”, said William Savage Landor. And a legal system bedevilled by delay, such as ours, inevitably suffers in various ways.

Sex crime victims shouldn’t have to suffer in silence ... Hong Kong’s laws are outdated, say activists

Secretary for Justice Rimsky Yuen Kwok-keung chairs the commission and, if people are to have faith in it, he must eradicate these delays. He might, for example, consider setting a two-year deadline for a subcommittee to report, with preliminary proposals required within a year.

Why Hong Kong child custody reform faces more delay despite lawyers’ support

Although the commission relies heavily on volunteers giving freely of their time, when a subcommittee is formed, its members must be instilled with a sense of urgency. For his part, Yuen must ensure that reports, once published, are expeditiously processed, without undue delay.

The Independent Commission Against Corruption has also become notorious for its delays, which greatly exceed those of other law enforcement agencies.

Glory days of the past do not absolve Hong Kong’s ICAC from its present problems

Total transparency is best for Hong Kong’s chief executive to clear up UGL payment controversy

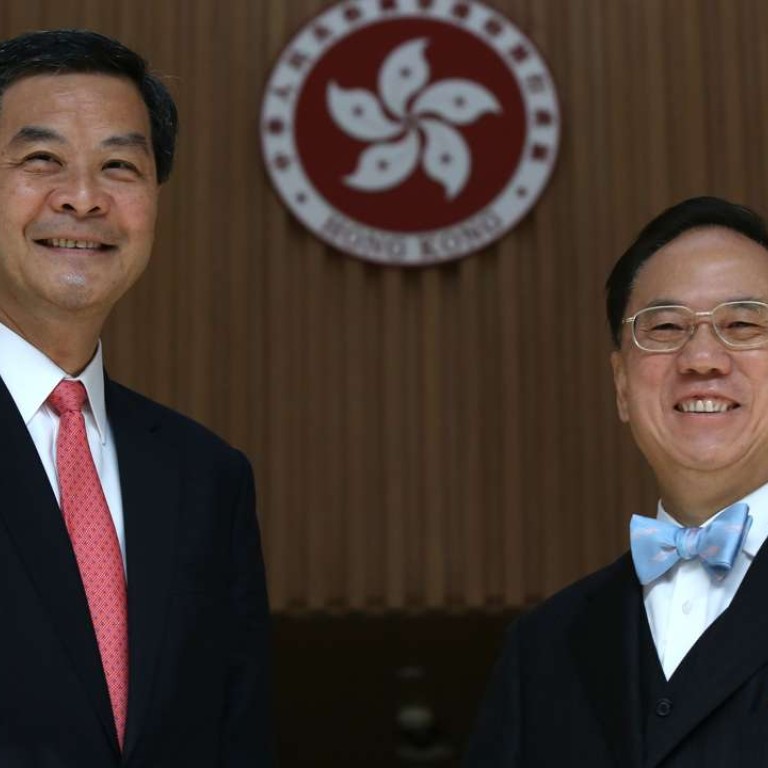

The ICAC’s Operations Review Committee, which oversees investigations, is chaired by Maria Tam Wai-chu, and she must now read the riot act to the commissioner, Simon Peh Yun-lu. Inordinate delays undermine efficiency and fairness, and also damage public confidence in the ICAC, and Tam simply cannot afford to look the other way. Peh must be under no illusions over his duty to ensure that cases are expedited, that internal expertise is nurtured and that, if necessary, more investigators of the right quality are recruited.

Hong Kong police accused of assault have case to answer

Once cases eventually reach the department of justice, delays have also arisen, partly because of the heavy workload. Although many senior prosecutors have departed of late, the people now at the top must show they can step up to the plate, and not leave difficult decisions to their subordinates, or outsiders. Tricky decisions must not, as a matter of course, be passed over to private lawyers, as happened, for example, with activist Ken Tsang Kin-chiu, whose assault case took a year to process after the papers were sent off to London for consideration.

Activist Ken Tsang gets five weeks in jail for assaulting police and resisting arrest during Occupy protest

If Yuen needs to strengthen his office by recruiting senior prosecutors from the Bar or elsewhere, perhaps as consultants, there is ample precedent for this.

Once the judiciary is finally seized of the more serious cases in the High Court, yet further problems are emerging, partly related to the shortage of substantive judges. On November 2, for example, although 25 courts were operating in the Court of First Instance, only 11 were presided over by permanent High Court judges. The other 14 courts all relied on temporary High Court judges – some of them retirees, pressed back into service from abroad, but also including two senior counsel – helping out for several weeks. By November 4, there were 13 substantive judges sitting in the Court of First Instance, and 13 acting High Court judges. While this expedient certainly buys time, it leaves much to be desired.

To be credible, a legal system must be efficient, and rampant delays have to be ruthlessly rooted out

To be credible, a legal system must be efficient, and rampant delays have to be ruthlessly rooted out. Once public confidence in the ability of our institutions to deliver justice within a reasonable time is lost, it may be very hard to restore.

Grenville Cross SC is a criminal justice analyst