Why Beijing saw fit to interpret Hong Kong’s Basic Law

Henry Ho says the NPC Standing Committee was forced to exercise its power to avert a dangerous precedent in Hong Kong, in a decision it did not take lightly

NPC interpretation adds nothing new to Hong Kong law, and is wholly unnecessary

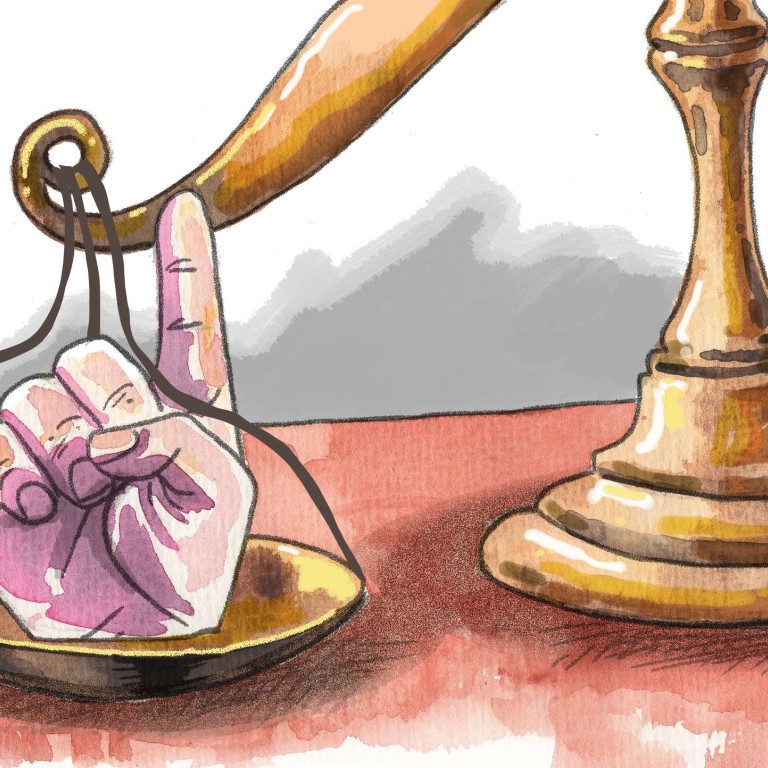

Does interpreting the Basic Law go against the rule of law? Hong Kong’s legal system, inherited from the British, is based on common law. While Article 8 of the Basic Law expressly provides that common law shall be maintained, its status is lower than that of the Basic Law. If any conflicts arise between the two, the Basic Law shall prevail.

That is probably the source of tension in recent years between Hong Kong and the mainland over the Basic Law. For many Hong Kong people, common law is the cornerstone of the city’s rule of law. Not only is it diametrically different from civil law, it also comes with its own set of reasoning, practices and methods of interpretation. Further, it is supported by a set of cultural norms and a value system. The key feature of the common law system is that only judges have the right to interpret the law; this makes it vastly different from both civil law and the mainland’s legal system.

This is what happens when you breach the Basic Law

The Basic Law is the constitutional document that guides the implementation of the “one country, two systems” policy. So, naturally, it is designed to accommodate both systems. Legal professionals in Hong Kong who have been trained under the common law system may find it difficult to accept the provision giving the legislature power to interpret the law. Still, most of the power of interpretation remains with Hong Kong courts. Thus, from Beijing’s point of view, a rejection of a National People’s Congress Standing Committee interpretation of the Basic Law by Hong Kong amounts to a denial of the nation’s sovereignty over the city.

The completely different ways of thinking of the two sides explains why Basic Law interpretations by the NPC are seen in Hong Kong as a major threat or, at the very least, a necessary evil. This is true even of Hong Kong officials and pro-establishment politicians, a sizeable number of whom accept such interpretations but believe they compromise the independence of the city’s judiciary, and even undermine the rule of law.

Hundreds of Hong Kong lawyers in silent march against Beijing oath ruling

However, the Standing Committee’s ability to interpret the Basic Law is part of the city’s legal system. It cannot be described as destroying the rule of law. As for judicial independence, it is secure as long as judges can make rulings of their own free will. Whether or not that ruling is later overturned by a higher court or by the NPC is another matter altogether, and cannot be said to affect judicial independence.

The question of whether the Standing Committee should interpret the Basic Law is best answered by the Court of Final Appeal. According to a number of judgments by the top court, the power of Hong Kong courts to interpret the Basic Law comes from the NPC Standing Committee, and its interpretations are binding for Hong Kong courts. The Standing Committee’s power of interpretation is right and proper. Even if a Hong Kong court does not petition the Standing Committee for an interpretation, the latter can still do so under any circumstances it deems appropriate.

It would set a dangerous precedent if independence advocates were allowed to enter the legislature

Therefore, the NPC is entitled to interpret the Basic Law, both in accordance with legal provisions and based on common law precedents. Concerning the view that it should exercise “restraint” from interpreting the law, it is a political issue, rather than a legal one.

In fact, the Standing Committee has been very respectful of the Court of Final Appeal. For example, after the Standing Committee’s ruling on the right of abode issue, in the hearing of the Chong Fung-yuen (2001) case, the top court split the interpretation of the Basic Law over the right of abode into two parts: ratio decidendi (the binding reason for the decision) and obiter dicta (the non-binding judgment on a case), according to common law practice. The Standing Committee’s interpretation applicable to the case was classified under the latter. Subsequently, it was ruled that all those born in Hong Kong to mainland parents enjoyed the right of abode here. In the following decade, more than 200,000 babies of mainland parents were born here.

After the ruling, a Standing Committee spokesman expressed concern over the verdict, but only said gently that the ruling was not consistent with the interpretation. But there was no further criticism or further interpretations.

A necessary intervention to keep separatists out of public office

Should the Standing Committee have interpreted the Basic Law while a court hearing is ongoing? To be fair, the Standing Committee was forced to act. The conduct of Sixtus Baggio Leung Chung-hang and Yau Wai-ching of Youngspiration has clearly touched the bottom line of “one country, two systems”. It would set a dangerous precedent if independence advocates were allowed to enter the legislature and use the privileges granted under the Basic Law (which they strongly oppose) to push for independence; this goes beyond the limits of freedom of speech.

An interpretation of the Basic Law is a serious matter and is treated as such. It has to be passed by the NPC Standing Committee, which meets once every two months. Does this latest interpretation signal that we would see more such interpretations while a court case is in progress? I don’t believe so. However, it is likely that the Standing Committee is showing that, on serious issues relating to “one country, two systems”, it won’t shy away from initiating an interpretation in order to nip in the bud a problem it feels could get out of hand. So, similar interpretations are possible in the future.

Henry Ho is a former political assistant to the secretary for development and a council member of the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies. This was translated from the Chinese