Are Beijing loyalists really ready for modern Chinese history to be taught to all Hong Kong students?

Gary Cheung says a new curriculum will give local secondary pupils the chance to study a number of ‘inconvenient truths’ about the nation’s post-1949 history

The lawmakers believe that the rise of separatist thought among young people in Hong Kong has to do with their shallow understanding of Chinese history. Priscilla Leung Mei-fun, for one, attributed the behaviour of two localists at the centre of the Legco oath fracas to the rise of a “rootless” generation – all because Chinese history was not properly taught.

Perspective key to teaching our children Chinese history

Revised history curriculum focuses more on Hong Kong but omits important elements of the past

Even so, Beijing-friendly politicians and mainland officials who spare no effort in pushing young people to learn more about Chinese history should be careful what they wish for.

All junior secondary students are in fact required to study Chinese history, with 89 per cent of secondary schools already teaching it as an independent subject for their junior secondary pupils. However, ancient history accounts for more than 70 per cent of the current syllabus of Chinese history at junior secondary level.

Should history lessons in schools include details about Hong Kong’s 1967 riots?

If Beijing loyalists want Hong Kong youth to better understand the Chinese people’s humiliation by foreign powers and appreciate the rise of the country’s international status in the second half of the last century, students will need to learn more about modern Chinese history. Currently, more than 40 per cent of secondary schools do not study events after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 because of insufficient teaching time.

Under the revised curriculum, which can be implemented as early as 2019, contemporary history would account for half of the curriculum. This will surely give students more time to learn about the “inconvenient truths” of China’s post-1949 history.

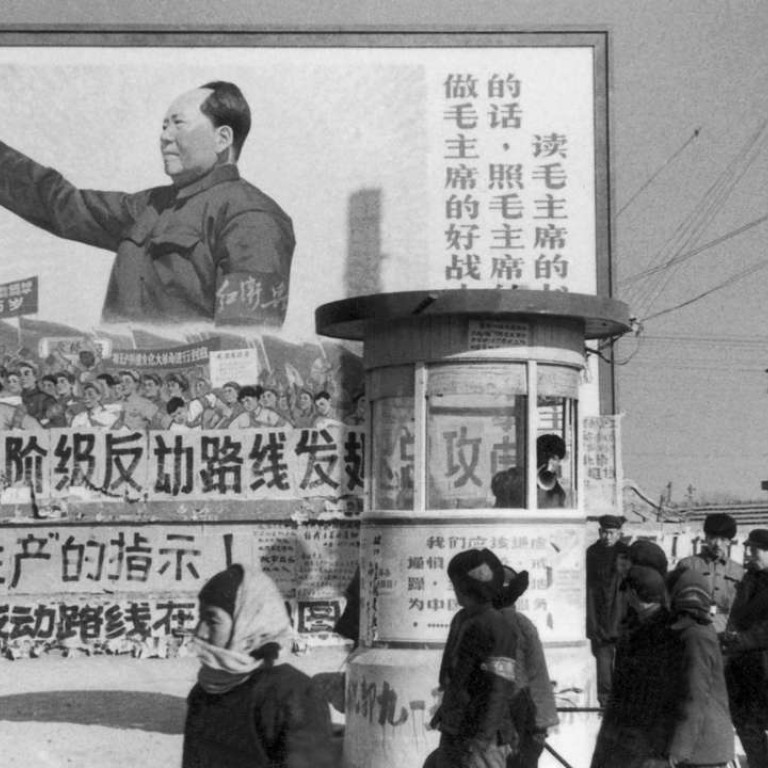

For starters, students will learn about how, in 1957, Mao Zedong (毛澤東) launched the anti-rightist campaign to “rectify the party”. Mao called his tactics “an overt conspiracy” to lure “the snakes out of their holes”. Hundreds of thousands of intellectuals who were accused of “launching a ferocious offensive” on the Communist Party were subsequently sent to labour camps to be re-educated. Following that, the 10-year Cultural Revolution, which started in 1966, saw countless politicians and intellectuals driven to their deaths, civilians killed in armed conflicts, and cultural relics destroyed.

I wonder if Beijing loyalists will kick themselves a few years down the road, when students are really learning more about what happened in China after 1949.

Gary Cheung is the Post’s political editor