On the belt and road, the Chinese civilisation is on the march

Peter T. C. Chang says Beijing’s ambition to build a pan-Asian sphere of common prosperity will affect far more than the region’s economy, and it would be wise to watch out for the civilisational fault lines

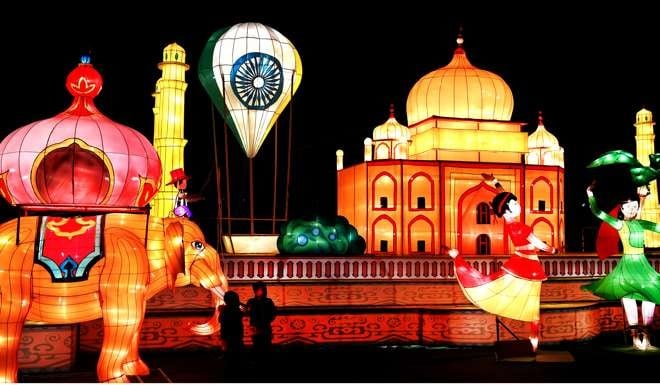

Retracing the ancient silk and spice trade routes, the belt and road seeks to reopen the economic corridors and re-energise the commercialism that once drew principalities near and far to the Middle Kingdom. Beijing’s endgame is to build a pan-Asian sphere of common prosperity, evoking both the celebrated adventures of Marco Polo and Zheng He’s expeditions, across the land and seas, all at once, this time deploying bullet trains and supertankers.

If actualised, the belt and road initiative will become an integrated economic zone unprecedented in scale, with the potential to positively affect a third of the world’s population, dwarfing America’s Marshall Plan, with which it has often been compared.

China’s belt and road can take its cues from the world’s first model of globalisation

This grand vision may be seen as the magnification and internationalisation of Xi’s “Chinese Dream”, into an “Asian Dream”. To be sure, this is as much a dispensation of Chinese soft power as it is a projection of geopolitical sway, to restore China’s regional, if not global, pre-eminence. For some, the markings of a modern metamorphosis of ancient China’s tributary system are unmistakable, as Beijing reclaims the suzerain role, commanding deference and allegiance from the peripheral vassal states.

This grand vision may be seen as the internationalisation of Xi’s ‘Chinese Dream’, into an ‘Asian Dream’