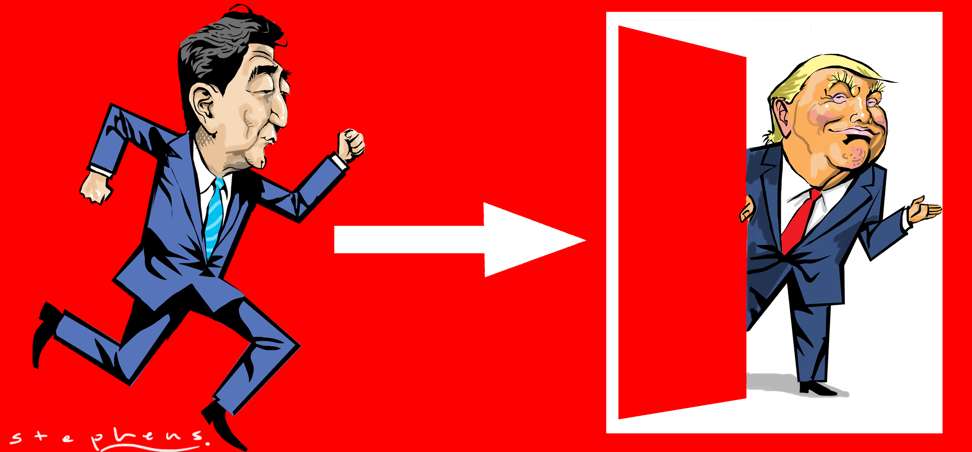

Shinzo Abe, friend of Trump and lacking Asian allies, is a true son of modern Japan

Jean-Pierre Lehmann says the prime minister’s cosying up to the US is consistent with the ideological arc of modern Japan, which more than a century ago decided to cast its lot with the West, turning its back on Asia

The secretive cult shaping Japan’s future

The rest, as the saying goes, is history. Japan learned and assimilated a lot from the West, primarily Britain, Germany, France and the US: constitutional law, jurisprudence, banking and finance, education, capitalism, modern military and naval strategy, railway building, industry, music, painting, sports (baseball from the US in 1873), lighthouses, textile manufacturing, watch making ... the list runs on. Until the undertaking of these reforms, ever since the fifth century, Japan had been a student of China and, to a lesser extent, Korea. Thus, “evil customs of the past” referred to Chinese learning.

A post shared by Donald J. Trump (@realdonaldtrump) on Feb 11, 2017 at 10:27am PST

How Japan and China can put past behind them and move on

Kishi in many ways embodied the Datsu-A, Nyu-O syndrome. During the war as the senior official in charge of the industrial policy of Manchukuo, he was responsible for the abduction of hundreds of thousands of Chinese slave labour, for which he earned the sobriquet Showa no yokai – “Showa-era monster”. For his war crimes, Kishi spent three years in Sugamo prison, but was released by the US as the Chinese liberation, the Korean war and the cold war changed the picture of the Asia-Pacific theatre. He was judged a good candidate to help lead Japan in a pro-US direction.

While sucking up to its American ally, Tokyo insults its former Asian colonies and enemies

Washington was not to be disappointed. In 1960, in spite of massive demonstrations by Japanese pacifists, Kishi, then prime minister, managed to ram through the Diet (Japan’s parliament) the ratification of the US-Japan security treaty that had been signed at the end of the US’ military occupation of Japan and that has served Japan so overwhelmingly well for the ensuing decades. Japan was transformed from America’s hated enemy to its pampered protégé, a status for which Kishi, who was dubbed “America’s Favourite War Criminal”, was an important architect.

Abe’s main obsession in kowtowing so obsequiously to Washington was to preserve the treaty and the alliance with the US. As far as one can judge from the fraternising last weekend, it would seem to be “mission successful”, though with Trump’s renowned volatility on the Japanese front, cautious optimism would be more in order than euphoria. Since the news of Trump’s election in November created a degree of panic in Tokyo, Abe has sought many means to brown-nose America. In December, he paid a “historic” visit to Pearl Harbour.

The lesson from Pearl Harbour that Donald Trump needs to learn

Watch: Japanese defence minister Tomomi Inada visits Yasukuni Shrine

Nothing short of a proper apology will bring full acceptance of Japan

Were Japan to re-enter Asia, contritely for the crimes committed in the past and constructively to bring about greater peace and prosperity in the turbulent continent, the world would be on a positive-sum game trajectory and the impact on Asia would be tremendous. As it is, by persisting in the Datsu-A, Nyu-O syndrome, tensions are exacerbated and the risks of war enhanced.

China was the US’ ally against Japan (and Nazi Germany) in the second world war, it would be a terribly tragic paradox if Japan and the US were to ally against China in a third world war.

Jean-Pierre Lehmann is emeritus professor at IMD, founder of The Evian Group, and visiting professor at the University of Hong Kong