Is China prepared for a new mantle in Central Asia amid the roll-out of its belt and road?

Raffaello Pantucci says China is slowly displacing Moscow as the regional guarantor, but Beijing does not appear to have fully considered the demands of its new role, especially in the context of its ambitious ‘One Belt, One Road’ strategy

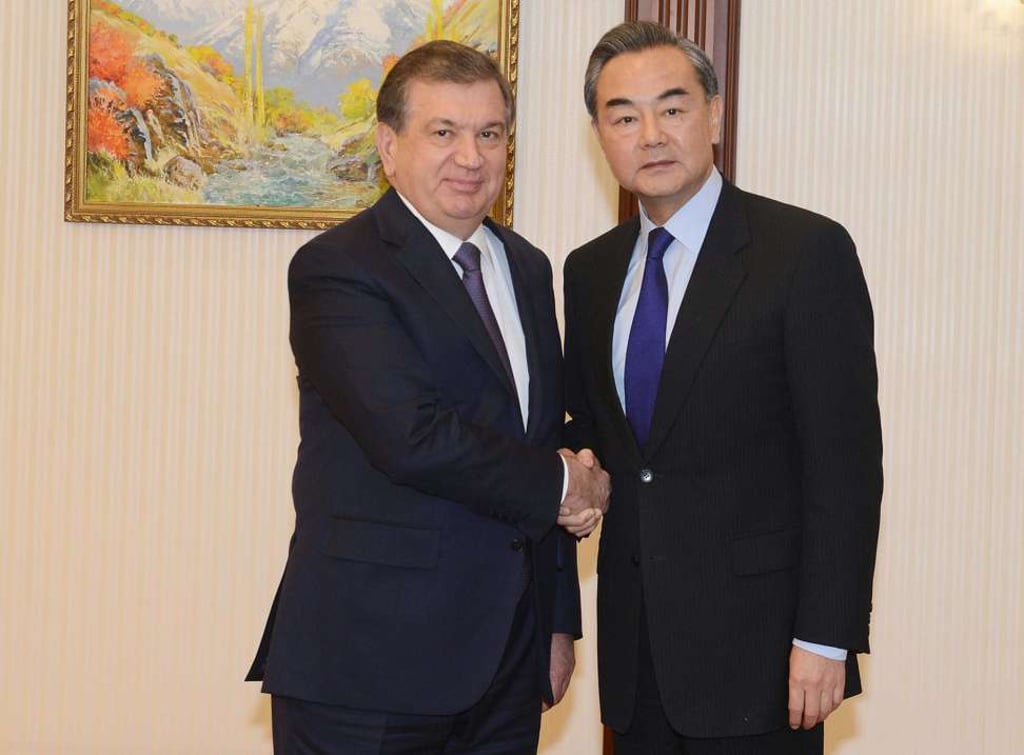

As the new president of Uzbekistan, Shavkat Mirziyayev, embarks on foreign visits, Beijing is likely to be fourth on the list, illustrating a broader set of tensions for China in its quest for a Silk Road economic belt through Central Asia.

Since independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Uzbekistan has maintained a strategic distance from Moscow and been unwilling to open its doors wide to Chinese investment. It also employs tight currency controls, making it hard for companies to withdraw profits.

All of this produces problems for China’s vision of open trade and economic corridors under the “One Belt, One Road” initiative.

Crucial to success of China’s belt and road plan? A little reciprocity, say experts

But the train line is part of a bigger vision to connect China through Kyrgyzstan to Uzbekistan, on to the Caspian Sea and European markets. This makes Tashkent fearful of just becoming a conduit for Chinese products, with little local capture. For Beijing, Tashkent’s hesitation means Chinese firms will have trouble investing in the economically attractive country. Also, tense regional relations mean crossing Central Asian borders remains one of the slowest ways of transit.