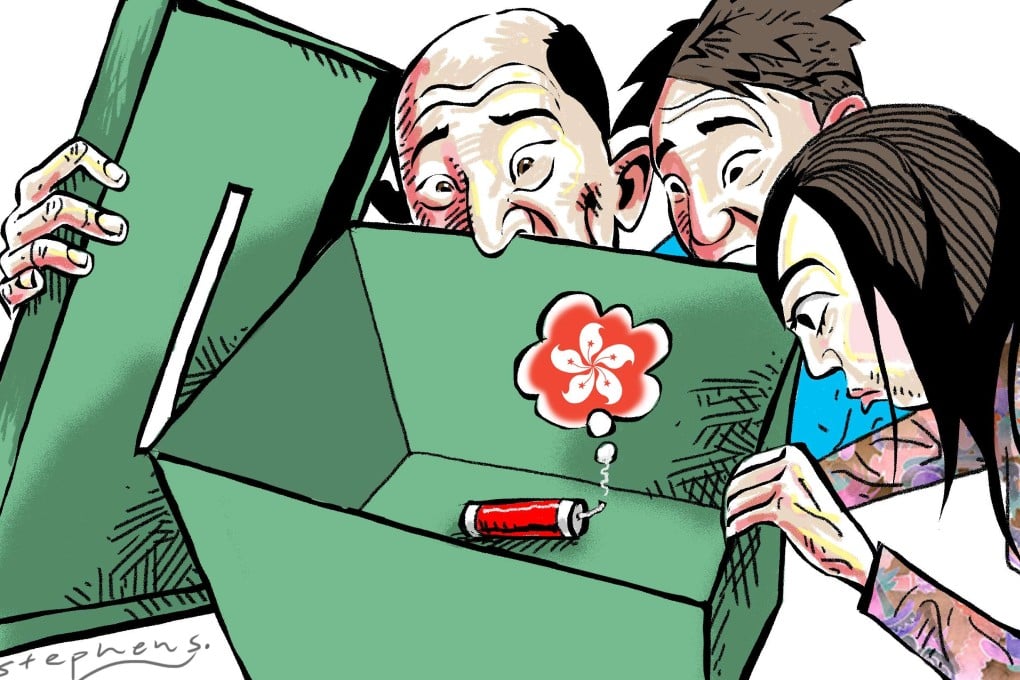

The chief executive election Hong Kong could have had

David Zweig considers what might have been under a rejected electoral reform plan, on the eve of the vote for Hong Kong’s next leader

Beijing did not offer us true democracy, as a nomination committee with a 50 per cent threshold would have prevented any pan-democrat from joining the territory-wide chief executive election. Under what at best could be called “Iranian-style democracy”, a coterie of appointed “mullahs” would have determined the candidates before allowing all the people to vote. But in Iran, the people have elected moderate clerics, greatly influencing Iran’s politics.

In Iran, the people have elected moderate clerics, greatly influencing Iran’s politics

To envision what Sunday’s election could have looked like, imagine two tents. One tent holds Hongkongers who favour greater democracy. They comprise 60 per cent of Hong Kong people who have consistently voted for pan-democratic candidates in the geographical constituencies. A smaller tent holds 30 per cent of the population who regularly back pro-government and pro-Beijing candidates. Another 10 per cent remain undecided which tent they prefer. Interestingly, mainland observers of Hong Kong society with whom I have talked recognise this 60-40 split within the Hong Kong electorate.

What pro-democracy forces in Hong Kong opposed is that under the August 31 mechanism, the two or three candidates running for chief executive on Sunday would have been drawn only from among politicians within the smaller, pro-government, pro-Beijing tent, while the 60 per cent of the citizenry within the democratic tent would have had no one representing their interests in the race.

Mainland sources say Beijing will keep political reform off the agenda over the next five years and, should it re-emerge after 2022, it will be less ‘generous’ than the August 31 proposal

Under the August 31 scenario, candidates would have to play to two constituencies: the 30 per cent who favour the government and Beijing, and the 60 per cent who favour further democratisation. Candidates would have to be careful to maintain support from people in the pro-government, pro-Beijing tent, as no one would want to surrender 30 per cent of the vote to their opponent.