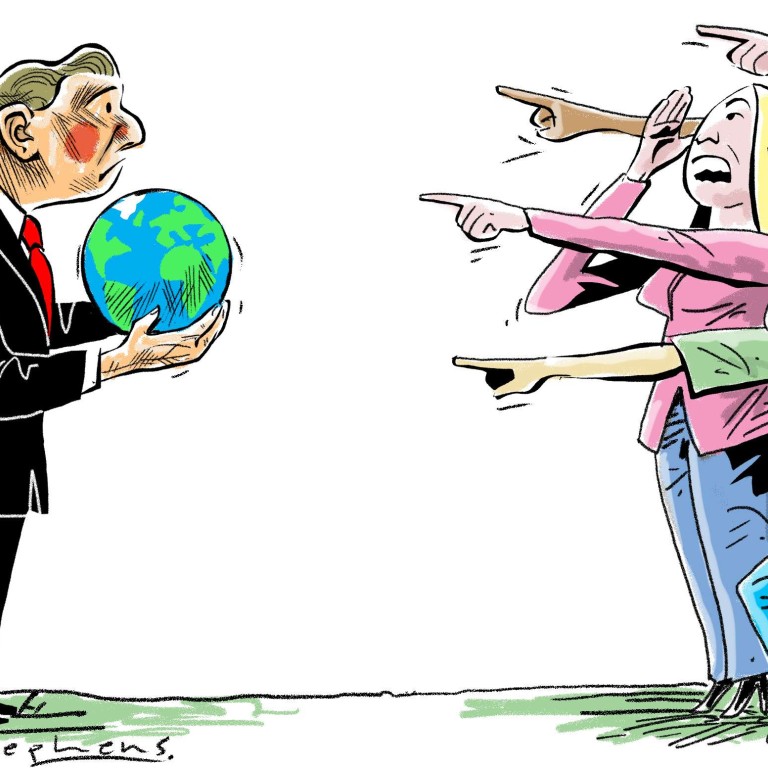

How the rise of populism brings many risks, but also potential benefits

Kingsley Chiedu Moghalu says some unwinding of globalisation may ultimately benefit the developing world, but the process, if chaotic, will undermine democratic institutions and good policymaking

Mitigating the risk requires avoiding arrogance towards those embracing populism. A dismissive response leaves us unable to manage implications for democracy and all issues of economic development in poor countries. Those who oppose populism must engage with it rationally in the political space with the force of their own ideas.

Political populism, characterised by a desire to assert domestic sovereignty and rejection of the “cult of the expert”, owes its rise to increasing rejection of the conventional wisdom by citizens who feel left behind by globalisation trends favouring the elite.

Globalisation’s not dead, it just has a new powerhouse – Asia

The rise of populism and its many implications flow from concerns about international forces supplanting the sovereignty of nations. It seeks to reverse the power of the international community by utilising the democratic legitimacy of the majority to reassert primacy of the national interest – seen by liberals as isolationism or “nativism” – in public policy.

Home-country multinationals that ship production – and jobs – abroad can anticipate a backlash. Multinationals will no longer receive benign preferences and protections in populist countries if they cannot prove their value to local economies.

Designing corporate initiatives to curry political favour erodes the free enterprise ethic. Business decisions may no longer be taken on the basis of market efficiency, injecting a heavy dose of partisan political considerations into corporate organisations.

Globalisation, whatever its virtues, was neither a benign phenomenon nor an agnostic one. It’s an agenda with global winners and losers

But, if a tariff war breaks out and US companies become the losers – a real risk – numbers will impose discipline on populism. Moreover, as US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross asserted, several European and Asian nations are also guilty of protectionist policies even as they proclaim the gospel of free trade.

Likewise, the European Union, which challenged domestic sovereignty, will be hardest hit as populism rises in France, Italy and the Netherlands. The EU is the most radical embodiment of the cosmopolitan world society world view, a political project masquerading as an economic one.

For developing nations, especially those in Africa, populism’s rise in the Western world may ultimately be beneficial, despite negative short-term impact. These countries will be forced to confront mistaken assumptions about development that relies on the “benevolence” of foreign aid. They must reconsider unquestioning acceptance of the inevitability of globalisation and their status as markets, not factory.

Industrialised countries, aided by technological superiority which produced value-added goods at competitive prices and the WTO treaty regime, flooded the markets of developing countries, leaving them import-dependent. Considering that more than 50 per cent of world trade is based on manufactured goods and the rude awakening offered by populism’s rise in the West, these nations should pursue the idea of “smart protectionism” – by deploying the “special and differentiated” provisions of the WTO treaty that can apply to less developed nations to prevent the dumping of Chinese goods in their markets and create enabling environments for modest industrial growth.

The process of global unwinding must be managed carefully. If chaotic, it raises the risk of other knock-on effects, and the risks of populism must be clear: first, attempts to substitute facts and empirical foundations with conviction as a basis for public policy create suboptimal outcomes.

Second, populism threatens the independence of impartial institutions that safeguard the integrity of democracy. Electoral victories should not become mob rule or a tyranny of the majority.

Third, populism, based on its binary convictions about bad and good guys and nations, as well as possible weakening of institutional frameworks, runs the risk of promoting instability in a nuclear world.

In an age of Brexit and Trump, is our post-truth world heading for a system reboot?

Populism, a product of democratic choice, can create mixed outcomes. Some, like the uprooting of corrupt and dictatorial regimes, are good. But in some cases, autocratic corruption can be replaced with a similar weakening of institutions and the conflation of populist sentiment with competent public policy, not to speak of new forms of corruption. Populism is likely to coexist uncomfortably with globalisation, colliding with realities of the world and public policy. One of these is that experts matter, even if they are not always right.

Kingsley Chiedu Moghalu is a professor of international business and public policy at The Fletcher School at Tufts University. Reprinted with permission from YaleGlobal Online. http://yaleglobal.yale.edu