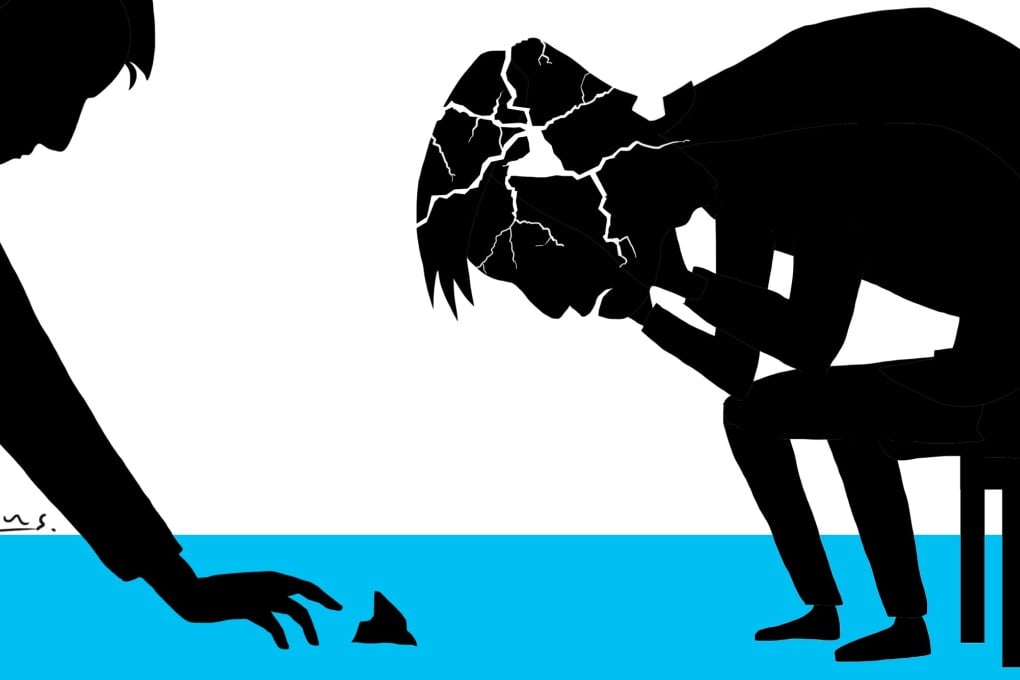

Mental health care in Hong Kong falls woefully short amid social stigma and lack of policy direction

Alfred C.M. Chan calls for a long-term government strategy on mental health care reform and tackling the shortage of psychiatric staff, along with greater social empathy for the mentally ill

Then there was Hong Kong’s much-discussed film Mad World , with its young protagonist struggling with bipolar disorder.

As his family disintegrates, he crumbles under the strain of having to care for his ailing, hysterical mother all by himself and allegedly causes her death, leading to his arrest and admission to a psychiatric hospital. His estranged father, a happy-go-lucky man, takes him back home and tries to help him along the rocky road to recovery.

Watch: Mad World director and screenwriter discuss the film

My attention is naturally drawn to issues related to discrimination and the rights of vulnerable groups, including the stigmatisation and ostracism of those with mental disorders, the burden on their carers, and a health care system that fails to help many of these people.

Mentally ill in Hong Kong need more government support

Mental illnesses, according to the WHO, are “generally characterised by some combination of abnormal thoughts, emotions, behaviour and relationships with others”. This definition encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions, from bipolar disorder to depression, anxiety, schizophrenia and intellectual disabilities and developmental disorders, such as dementia and autism.

While the government keeps no record of the overall number of residents with mental illness, the Hospital Authority Mental Health Service Plan for Adults 2010-2015 extrapolated from worldwide data that the prevalent rate would be 15 to 25 per cent. This means somewhere between one and nearly two million people – almost the population of Hong Kong Island – are struggling with some form of mental illness, diagnosed or otherwise.

MTR firebomb attack throws spotlight on mental health care

People with mental illness used to be confined in “madhouses” and be subjected to undignified treatment. In response to global trends and the rising demand for human rights for all, Hong Kong today relies heavily on community care to rehabilitate this group subsequent to their deinstitutionalisation.

What has gone away is the indiscriminate locking up of people with mental health problems, but prejudice lingers