How US fears over the Russian threat led to the rise of China

Robert Boxwell wonders whether US interests may have been better served if the ‘normalisation’ team had had a less sanguine view of ties and trade with China

China’s growth into an economic and technical power rivalling US supremacy in the Pacific was an unintended consequence of what Nixon and Kissinger began in efforts to bring the Vietnam war to an end and counterbalance the Soviet nuclear threat, which they saw as the critical issues of their time. But by the time Brzezinski and Carter finally completed normalisation in December 1978, Vietnam was in America’s rear-view mirror and the Soviet nuclear threat was being brought under control.

The danger that China would grow strong from trade with the US – and other advanced countries – was debated widely before normalisation. The debate was a broad one, addressing, as a technology assessment report commissioned by Congress noted in 1979, the “costs and benefits of the United States’ selling technology to and expanding its commercial relations with the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and the People’s Republic of China”.

One side argued that such technology transfer was necessary and would contribute to “a lasting structure of peace”. In any event, the argument continued, “corporate interest should be more than adequate to protect the US from suffering substantial economic losses through trade in technology; it is, after all, in the interest of every corporation to protect its position of technical leadership”.

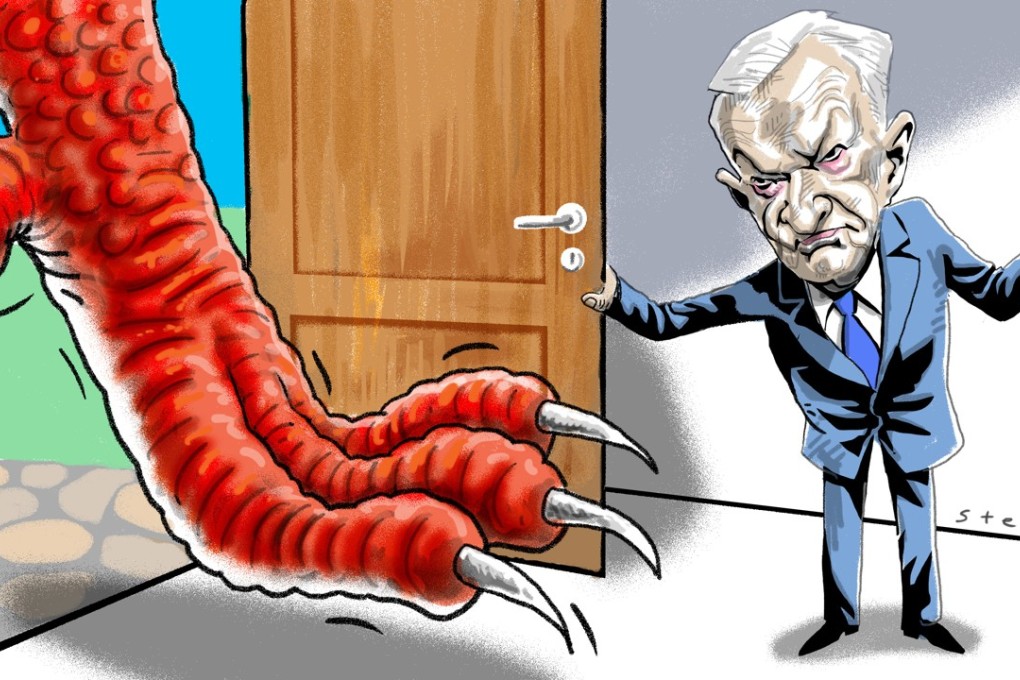

China benefitted tremendously from a belief by [Brzezinski and Kissinger] that Beijing was less of a danger than Moscow

The other side’s argument was not so optimistic: through trade, “the West is being slowly bled of its most important assets by nations it has every reason to distrust ... The only safe course is to deny assistance to our adversaries wherever possible, using trade only as necessary to extract political concessions.” The irony of the mention of an economically strong country “using trade to extract political concessions” is hard to miss in the current environment around the Asia-Pacific.