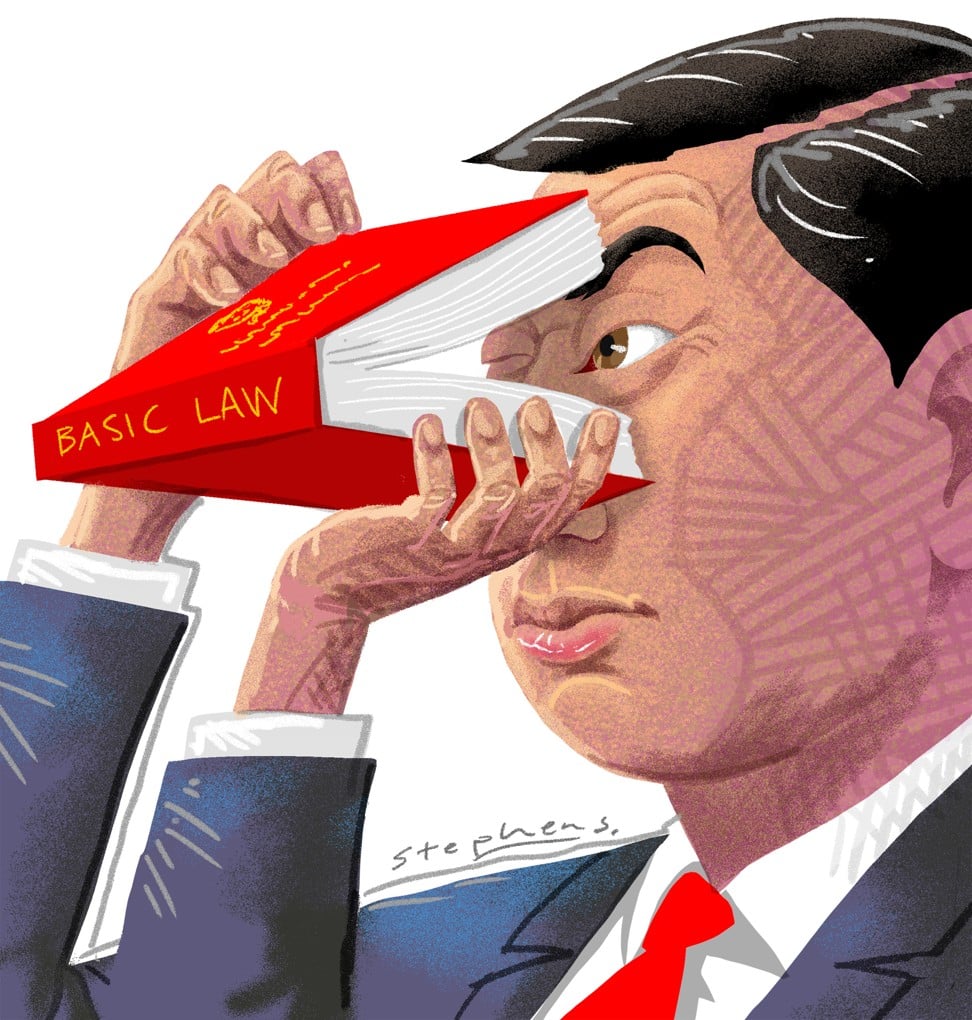

How Hong Kong’s Basic Law can serve the interests of all China

Simon Young says a narrow view of the Basic Law is partly to blame for the ‘one country’ versus ‘two systems’ deadlock in Hong Kong. It’s time to widen the perspective to see what the SAR can offer the country

However, the internal perspective has proven to be divisive, one that sees continuous tension and conflict between the “one country” and the “two systems”. The conflict is well known, if not tiresome. One sees it in recent speeches on the success or failure of the Basic Law.

It’s time to resolve conflicts over ‘one country, two systems’

The side trumpeting the “one country” hails the Basic Law’s first 20 years, pointing to Beijing’s restraint and the many ways in which Hong Kong has been allowed to prosper. To this group, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress has made “only” five interpretations of the Basic Law, each measured and made for good reasons. Those calling for independence or self-determination are regarded as ungrateful, spoiled, and soon to be, if not already are, enemies of the state unless stronger measures are taken.

Hong Kong’s handover anniversary is an opportunity to restore faith in ‘two systems’

Those trumpeting the “two systems” highlight the “high degree” of autonomy promised to Hong Kong in the Basic Law and the Sino-British Joint Declaration. To them, one Standing Committee interpretation is one too many, and the five we have had have seriously damaged common law judicial independence. What is there to celebrate when press freedom has been deteriorating, Chinese mainland authorities have increasingly encroached on Hong Kong’s autonomy, and the local government has been unable to defend Hong Kong’s interests. The government’s “hardline approach” is to blame for the failure of “one country, two systems”, and independence talk is but a natural consequence of the political reform void.

In the internal perspective, Hong Kong remains a ‘borrowed place on borrowed time’, with 2047 standing in the place of 1997

As the internal perspective looks mainly to the interests and continuity of Hong Kong, there is little room to consider Hong Kong-mainland relations. The two sides are single entities unable to have a constructive dialogue on constitutional development. During the 2014 universal suffrage debacle, the central government’s Standing Committee decision was a top-down monologue, while local protesters’ provocative means drowned out their message and those of others.

In this internal perspective, Hong Kong remains a “borrowed place on borrowed time”, with 2047 standing in the place of 1997.

The two sides have divergent ideas on how to resolve the conflict. The “one country” camp would invest in a kind of brainwashing, and recommend for the incorrigible, first, elimination from the political system, then incarceration. For the autonomy camp, there are different responses: protest, obstruct, disobey, veto and exit. While those in the autonomy camp await a new president, those in the other camp await 2047.

What more does China want from Hong Kong 20 years on from handover?

Balancing ‘one country’ with ‘two systems’: a look back at 20 years of an often uneasy relationship between Hong Kong and Beijing

In contrast to the dismal internal perspective, there is another perspective of the Basic Law rarely mentioned. The external perspective sees the Basic Law as serving national interests and the nation’s interests in the global community.

The autonomy camp does not see the external perspective, or they see it as irrelevant, as they continue to fight micro battles with the “one country” camp and the Hong Kong or mainland governments. Some do not see the nation at all, whether because they are legally barred from entering the mainland or figuratively because of pro-independence thinking.

Why not grant Hong Kong officials the power to conduct boundary checks on behalf of the mainland? A select group of Hong Kong officers could be specially trained by mainland officers and sworn to secrecy on the intelligence obtained from the mainland security network. Hong Kong would maintain its autonomy while contributing to a matter of national importance.

While the precise arrangements have yet to be announced, it seems highly unlikely the mainland government would entrust Hong Kong with such powers.

In State Council white papers and the speeches of the foreign minister, Wang Yi (王毅), even on topics of rule of law and human rights, Hong Kong is not cited as an exemplar. When mentioned in a recent speech by Wang, it was only to say that China had opposed “foreign interference in Hong Kong and Macau affairs”. Recently in London, Hong Kong’s secretary for justice lauded the city’s system of overseas judges in the Court of Final Appeal as an “innovative formula” that “proved to be a success”. I cannot recall ever hearing a mainland official giving similar praise. Rather, one hears voices in the “one country” camp calling for the system to be dismantled. The judiciary, which enjoys both public confidence and international repute, should instead be a matter of national pride. One wonders whether such calls do a disservice to the national interest.

It is in Beijing’s interests to ensure Hong Kong doesn’t wilt and fade

As we mark the first 20 years and reflect on the next 20, it is time for all to take a fresh look at the Basic Law to get beyond the conflict of the internal dimension. The very survival of the Basic Law beyond 2047 may well depend on finding common ground in a new perspective.

Simon Young Ngai-man is professor and associate dean in the Faculty of Law, the University of Hong Kong