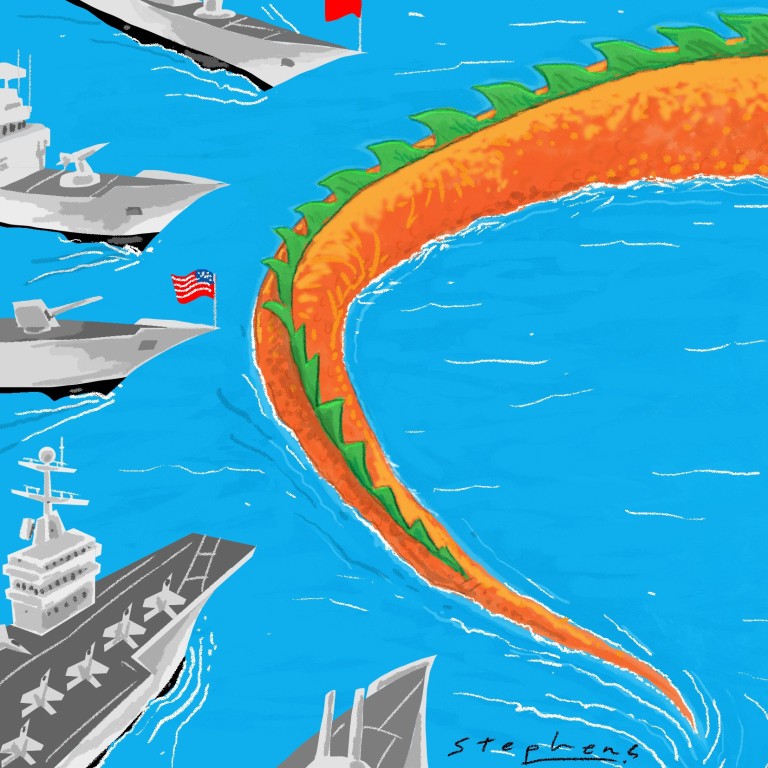

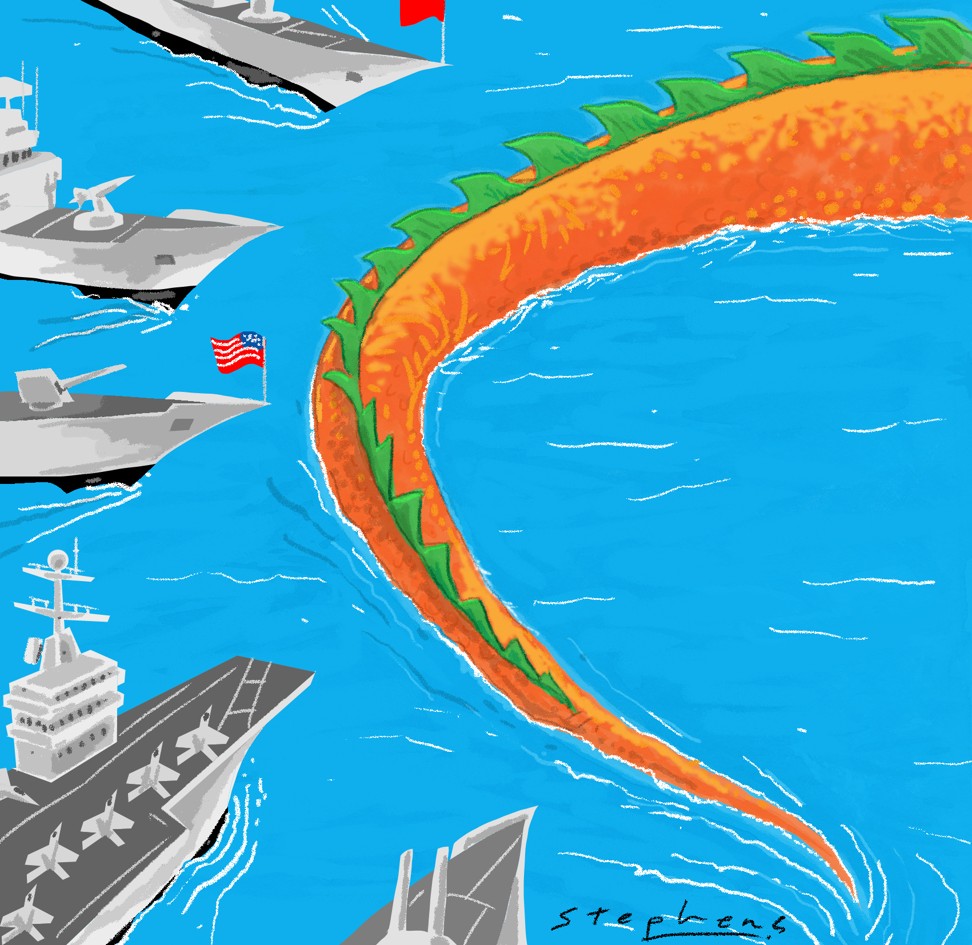

Beijing now calls the shots in the South China Sea, and the US and Asean must accept this for lasting peace

Mark J. Valencia says China’s perceptual domination of the sea lanes is complete and, military grandstanding aside, the US and others in the region will need to focus on realistic goals, rather than desirable ones

What’s China’s ‘nine-dash line’ and why has it created so much tension in the South China Sea?

Watch: China dismisses South China Sea ruling

The irony is that the contest has been, and still is, primarily perceptual in nature. No commercial shipping has been affected, despite the constant US concern with “freedom of navigation”, nor is it likely to be in peacetime, given China’s heavy dependence on ship-borne trade.

In a real war, China’s military installations would be highly vulnerable to attack and destruction

Indeed, China is just as, or even more, concerned that the US might try to block its shipping traffic in the event of hostilities. Most importantly, a point often lost in the diplomatic hand-wringing is that, in a real shooting war, China’s military installations would be highly vulnerable to attack and destruction; they give China little, if any, strategic advantage in a clash with the US.

Watch: Duterte pledges to avoid South China Sea issue in Beijing

So what are the options for the United States in the near term?

One possibility, advocated by US hardliners, is for it to physically confront China over its actions and claims in the South China Sea. This could include forcing China’s forces off the features it occupies or even blockading them. Another suggestion is for the US to gain military access to the other claimants’ bases there and thus compete in a mini arms race with China.

But this is highly unlikely. The current US strategy to prevent China’s build-up there – if there was or is one – has not worked so far. Moreover, as prominent Australian analyst Hugh White observes, Washington has shown little appetite for engaging in a confrontation with China in its own backyard, where it might take heavy losses and not win quickly or outright. The US also reckons that support for its “friends and allies” or for nebulous concepts, like the international order or the freedom of navigation, are not sufficient reasons to do so.

The US has no history of, or predilection for, sharing power with anyone

More importantly, it perceives that its “friends and allies” do not want to see a US-China confrontation, at least one that will involve or negatively affect them, and it is difficult to imagine one that would not.

Worst of all, this would be a bad idea because, as White suggests, China believes the US does not have the will and wherewithal to meaningfully confront it and would thus press on. If the US was not bluffing, as China would think, the result could well be war.

Another option, also unlikely, is for the US and China to proactively agree to a modus operandi that accommodates Chinese concerns and shares management of the regions’ security situation. But the US has no history of, or predilection for, sharing power with anyone – and this is likely to continue in the Trump era.

Trump’s honeymoon with China seems to be ending

US accused of sabotaging peace and stability in South China Sea

More US-China military incidents are likely, but hopefully none will cross the threshold to open conflict – although they will likely come increasingly closer to it.

In any of these scenarios, the Southeast Asian claimants – and the rest of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, are increasingly sidelined. As China rises in power, the Western-built and US-led international order, particularly the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, continues to haemorrhage, and there is really little that Asean or the US can do about it.

Asean’s centrality in security affairs for the region becomes an ever more unobtainable goal in the face of big power rivalries.

The point is that the sooner the other claimants, Asean as a whole and the US face reality and embrace the art of the possible, rather than the desirable, the more likely it is that they can find and accept a modus operandi that will maintain peace in the South China Sea.

Mark J. Valencia is an adjunct senior scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou, China