Trump’s threats at UN to ‘totally destroy’ North Korea demonstrate little relationship with reality

Donald Kirk writes that Trump’s over-the-top declaration can’t hide the fact that military action against the North would be deeply unpopular at home, costly and opposed by North Korea’s neighbours

If nothing else, Trump’s speech at the UN General Assembly will be remembered as one of those classic moments at which a head of state spoke for shock effect to a more or less captive audience. His words were reminiscent of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in 1960 banging a shoe in protest against a speech, or Palestine Liberation Organisation leader Yasser Arafat in 1974 wearing a pistol belt, saying he carried “an olive branch in one hand and a freedom fighter’s gun in the other”.

Watch: The most dramatic speeches in UN history

For Trump, the gulf between rhetoric and reality is often quite wide

Let’s imagine, hypothetically, the consequences of a pre-emptive strike on a missile facility. Would North Korean artillery really open up on Seoul and Incheon, as forecast? Might Kim Jong-un order missile shots aimed at the US military base at Pyongtaek? Would the North Koreans launch mid-range missiles in the general direction of the US air and naval bases on Guam?

The cold, calculated logic behind North Korea’s missile tests

15 perspectives on the North Korea nuclear crisis

They also had to have ignored the proposal of retired Yonsei professor Moon Chung-in for a freeze on North Korean nuclear and missile tests in exchange for a freeze on US and South Korean war games. Professor Moon, an “adviser” to President Moon, has been spouting the same line for years. Obviously North Korea would not be cutting out its own war games while going on about fabricating missiles and nukes.

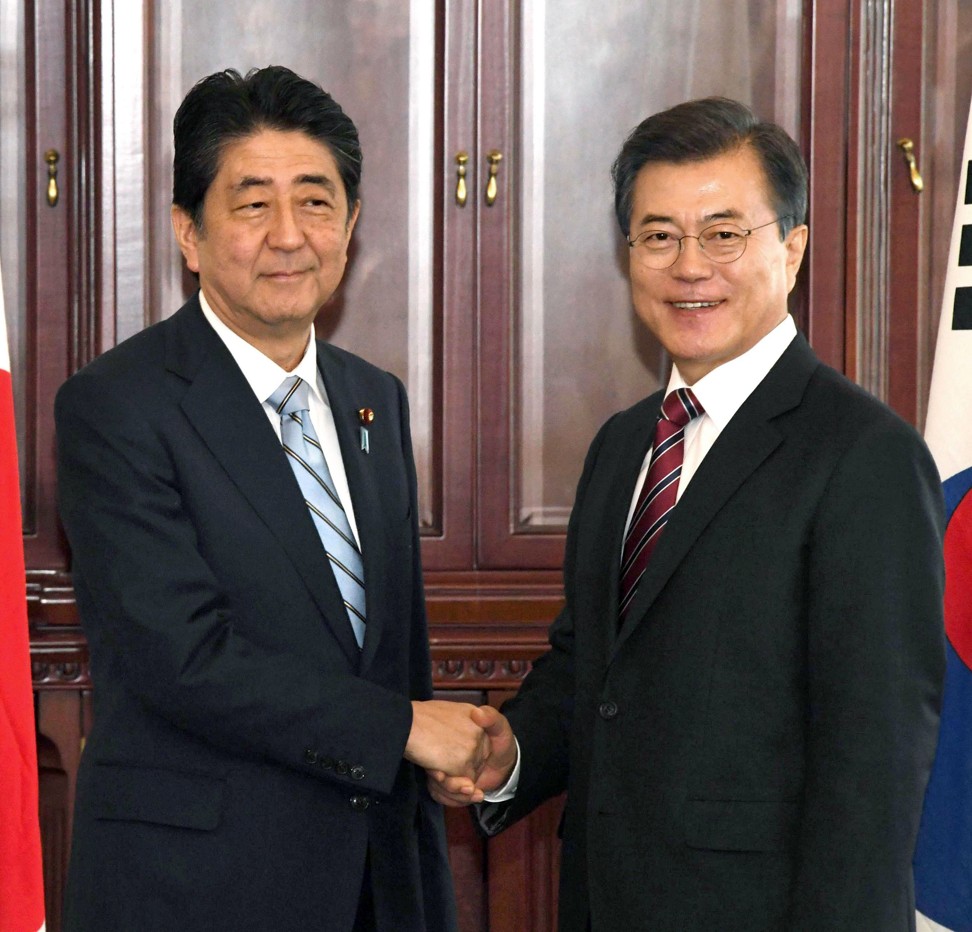

Can Moon Jae-in find a path to reconciliation with North Korea?

For President Moon, the answer still lies in persuading the North of dialogue on some level. He may not be fulfilling the demands of leftists anxious to disavow the US alliance, but he’s not going along with all of Trump’s notions either.

After the storm over Trump’s words dies down, where do we go from here? Trump did say the US would destroy North Korea in “defence”. Kim Jong-un has often said he needs nukes for “defence”. At least that’s one word on which they both agree.

Donald Kirk is the author of three books and numerous articles on Korea