Advertisement

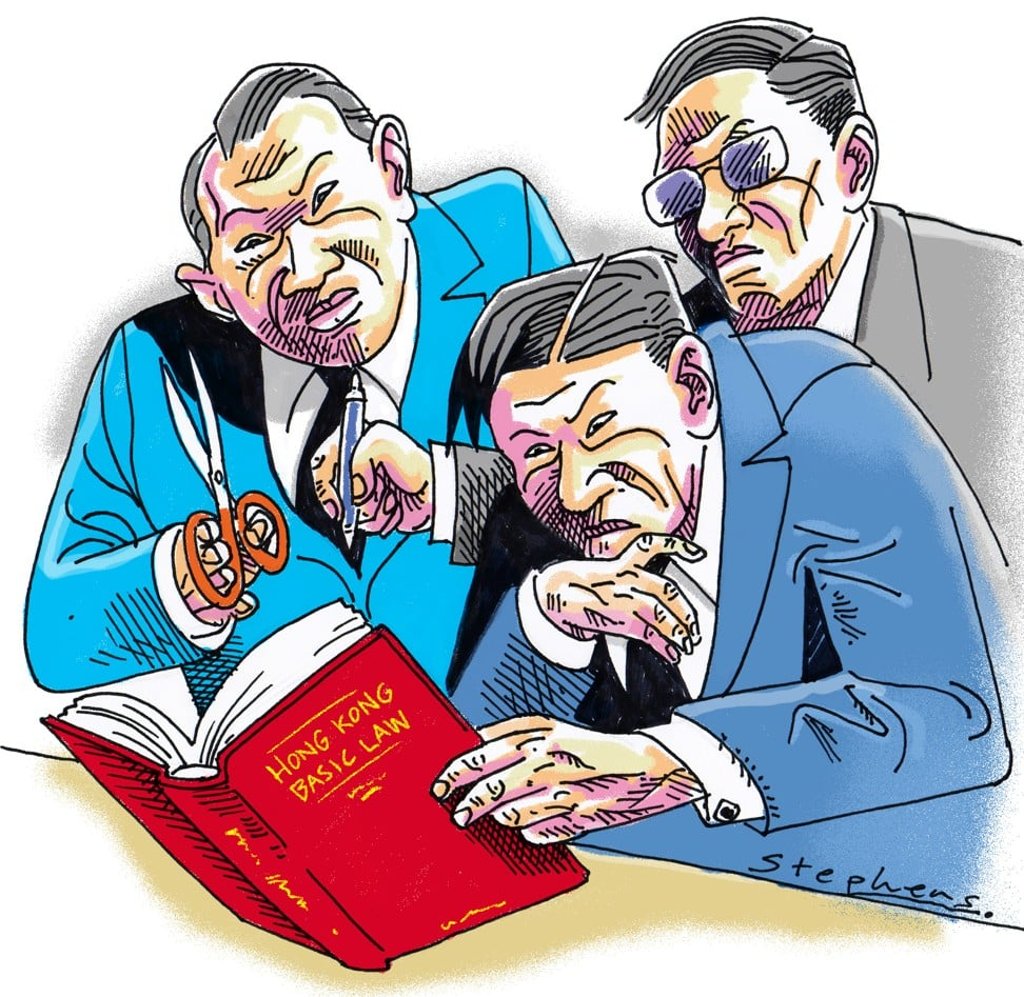

Opinion | Can Beijing’s power to interpret Hong Kong’s Basic Law ever be questioned?

Cliff Buddle says in light of the Court of Final Appeal’s recent refusal to allow two lawmakers disqualified for improper oath-taking to even make their case before the top court, it is worth revisiting its stirring first judgment involving interpretation of the Basic Law, in 1999

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

The booing of the national anthem at football matches, the posting of pro-independence banners at universities and the provocative remarks made by some lawmakers when taking their oaths are all symptoms of the same problem. There are, no doubt, complex reasons for these various expressions of opposition to the central government in Hong Kong since the Occupy pro-democracy protests in 2014. But frustration with the status quo and a perception that Hong Kong’s autonomy is being eroded is one of the key factors driving discontent.

The direction which the “one country, two systems” arrangement seems to be taking, with more intervention from Beijing, is causing discomfort, and not only among those inclined to resort to extreme actions. This explains the strong response to the jailing of student leaders in August for an unlawful protest, with claims from some that political motives lay behind the judgment.

Advertisement

There is, understandably, much concern that the Hong Kong judiciary should remain independent. It is the most autonomous institution under the constitutional framework put in place by the Basic Law. We rely on our judges to protect our rights and uphold the rule of law, core elements of the city’s separate system. In the absence of a democratically elected government and no independent body to rule on constitutional disputes between Hong Kong and the central government, the judiciary plays a vital role.

Hong Kong’s legal system is separate from that which exists on the mainland. But the two meet when there is a need for an interpretation of the Basic Law. The power of the National People’s Congress to issue interpretations which bind the courts provides Beijing with a means of asserting its power in Hong Kong. The question of whether there are any limits on that power is, therefore, an important one.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x