Hong Kong’s lost youth need help to see themselves in China’s future

Regina Ip says the generations of young people born of a hybrid East-West culture are now suffering an identity crisis that cannot be solved by simply mandating respect for the nation by law

Recent statements by Beijing officials on Hong Kong’s need to fulfil its constitutional obligation to protect national security and enhance national identity clearly show that the central authorities are losing patience with the SAR government’s inability to enhance greater acceptance of the nation.

National flags, emblems and anthems are rightly regarded by most countries as inviolable symbols of the nation. They represent the state, and the obligations the state expects of its people in reciprocation of the state’s protection.

Hong Kong youth dream of democracy, fairness and a greener world. So does China

In the past 20 years, the SAR government has lost every battle to protect national security and enhance national identity. That is not because Hong Kong people are unappreciative of the tremendous achievement of China’s leaders in modernising the country and catapulting it to a leading position in the global community, or ungrateful for the help Beijing has given Hong Kong whenever its small but open economy is mired in crisis.

The reasons for Hong Kong people’s resistance to fulfilling its responsibilities towards the state are rooted in a combination of historical, political, ideological and cultural factors. Where Hong Kong youth are concerned, the cultural factor deserves closer scrutiny.

According to acclaimed Hong Kong author Chan Koon-chung, who now lives in Beijing, Hong Kong people’s sense of identity has been shaped by eight cultural systems – traditional Chinese culture, the traditional local culture of the Guangdong province, the traditional local culture of Chinese provinces outside Guangdong, the culture of “new China” in the Republican era, the British colonial culture, the nationalist and party-centred culture of China after the Communist takeover (which is being increasingly felt in Hong Kong), the Anglo-American-based Western culture, and, in recent years, a strong Cantonese-based local culture.

It would be futile for localists to use Cantonese as a cultural and linguistic barrier to segregate Hong Kong from the rest of the nation, but a unique Cantonese-based Hong Kong lingo permeates local life, rendering Hongkongers, especially young people who grew up after the reunification, almost a different people with their own values, predilections and habits of mind.

While the older Chinese in Hong Kong – the immigrants from mainland China and the baby boomers – are far more attached to the mainland and comfortable with their Chinese cultural heritage, the younger generations were brought up in a hybrid culture which renders them emotionally and linguistically neither part of China nor part of the Western world.

Hong Kong soccer fans boo the national anthem at a match in October 2017

Young Hong Kong Chinese born out of this hybrid culture have an identity crisis. They are unable to connect with people from the mainland, unwilling to come out of their shell, and unsure of who they are and what they might become. Their insistence that they are Hongkongers, not Chinese, betrays a deep crisis of confidence. Their refusal to be assimilated is rooted in fear – fear that they will be overwhelmed and lost in the great melting pot of the Chinese nation.

Despite efforts by universities to provide more dormitories on campus to give students a more rounded college experience, the tendency of local students to stick with fellow locals and live separate from mainland or international students speaks volumes about the average Hong Kong youth’s unwillingness to cross cultural borders.

Hong Kong’s youth must stop demonising China to have a brighter future

What’s the Greater Bay Area plan? Hong Kong’s young people don’t know either

The nation has work to do as well. It must try to sell itself to young people in a more fun and light-hearted way. It should also offer a more expansive concept of Chinese citizenship – encompassing not only people’s duties and responsibilities, but also a more divergent set of beliefs, convictions and aspirations.

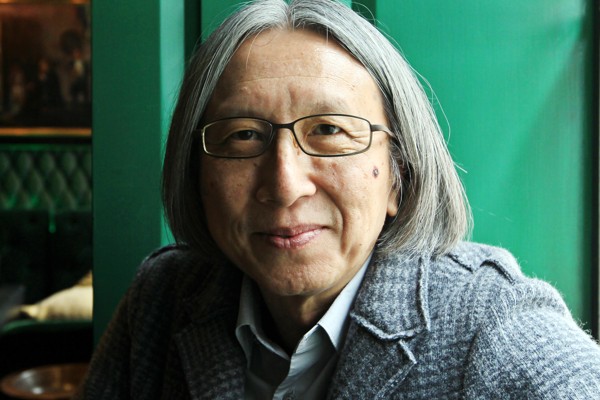

Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee is a lawmaker and chairwoman of the New People’s Party