Advertisement

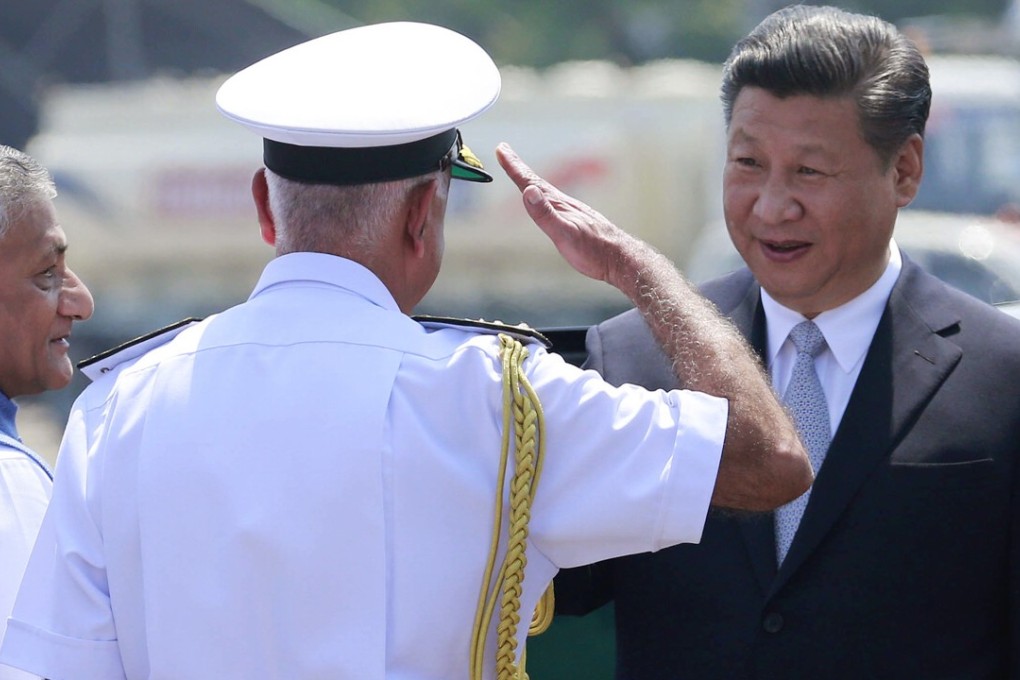

The ‘Indo-Pacific’ has always been about containing the rise of China

Abhijit Singh says that the use of the term to describe an emerging India-Japan-US-Australia alliance as a balance against Beijing is not a distortion of the term’s original meaning; it is the fulfilment of it

4-MIN READ4-MIN

Since US President Donald Trump repeatedly used the “Indo-Pacific” term during his first tour of Asia, there has been much hairsplitting over the term’s geopolitical implications. There has also been analysis of its implications for the maritime strategies of the United States, Japan, Australia and India, who have revived their Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.

In a recent Washington Post article, Indian naval captain Gurpreet Khurana railed against Trump’s distortion of the “Indo-Pacific”, a term Khurana is credited with coining. He lamented Trump’s use of the term to isolate China, saying this departs significantly from its original purpose, to highlight a cooperative dynamic from the Indian Ocean and the Pacific.

Khurana represents a section of South Asian analysts who harbour utopian notions of congeniality, with a vision of an egalitarian security order spanning the “entire maritime underbelly of Asia”. The problem with the idealist illusion of a peaceful Indo-Pacific is its underlying premise that security cooperation across distant oceanic spaces is driven by converging values, not the core national interests of participants.

‘Indo-Pacific’: containment ploy or new label for region beyond China’s backyard?

The truth is the Indo-Pacific has always been about balancing the rise of China. By 2006, Japan had shifted away from the “friendship diplomacy paradigm” with China to a mixed strategy involving elements of realistic balancing as a hedge against future threats posed by China. A majority of Japanese observers then predicted a China-Japan arms race in East Asia. Tokyo needed a framework to draw in more partners to balance China, and the Indo-Pacific was a way of underlining the challenge posed by the Chinese military to maritime powers in Asia.

Xi Jinping and Shinzo Abe can lead the ‘Asian century’, if China and Japan are able to bury the past

India, meanwhile, had its own worries. Since the early 2000s, Beijing’s rising power in Asia had caused nervousness in New Delhi, where disquiet over rapid Chinese military modernisation led to intensification of defence engagement with member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. It was a period that saw many bilateral agreements signed and a visit in July 2005 by INS Viraat – then India’s only aircraft carrier – to three Southeast Asian states. India moved with urgency to build on a defence assistance agreement with Vietnam, committing to assist Hanoi in repairing Russian-made fighters and providing training to Vietnamese pilots. A military cooperation pact with Singapore allowed the latter’s air force to use Indian airbases to conduct military exercises. In 2007, India, Japan, Australia and the US held their first and only Quad naval exercises in the Indian Ocean, inviting the Singapore Navy to join the engagement.

Advertisement

US, Japan, India, Australia ... Is Quad the first step to an Asian Nato?

None of these events occurred in a geopolitical vacuum. Delhi didn’t claim its maritime cooperation with Asean states and Pacific naval powers was driven solely by the need to secure sea lines of communication or fight pirates, gun-runners and smugglers. Underlying India’s maritime moves in Southeast Asia was the need to contain China.

The US objective of securing strategic balance in Asia is to the region’s wider benefit

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x