Belt and road, or a Chinese dream for the return of tributary states? Sri Lanka offers a cautionary tale

Patrick Mendis and Joey Wang say Sri Lanka’s debt trap should serve as a warning on Chinese largesse, amid doubts over efficient resource allocation by China’s banks and concerns that borrowing nations may be committing to a Faustian deal

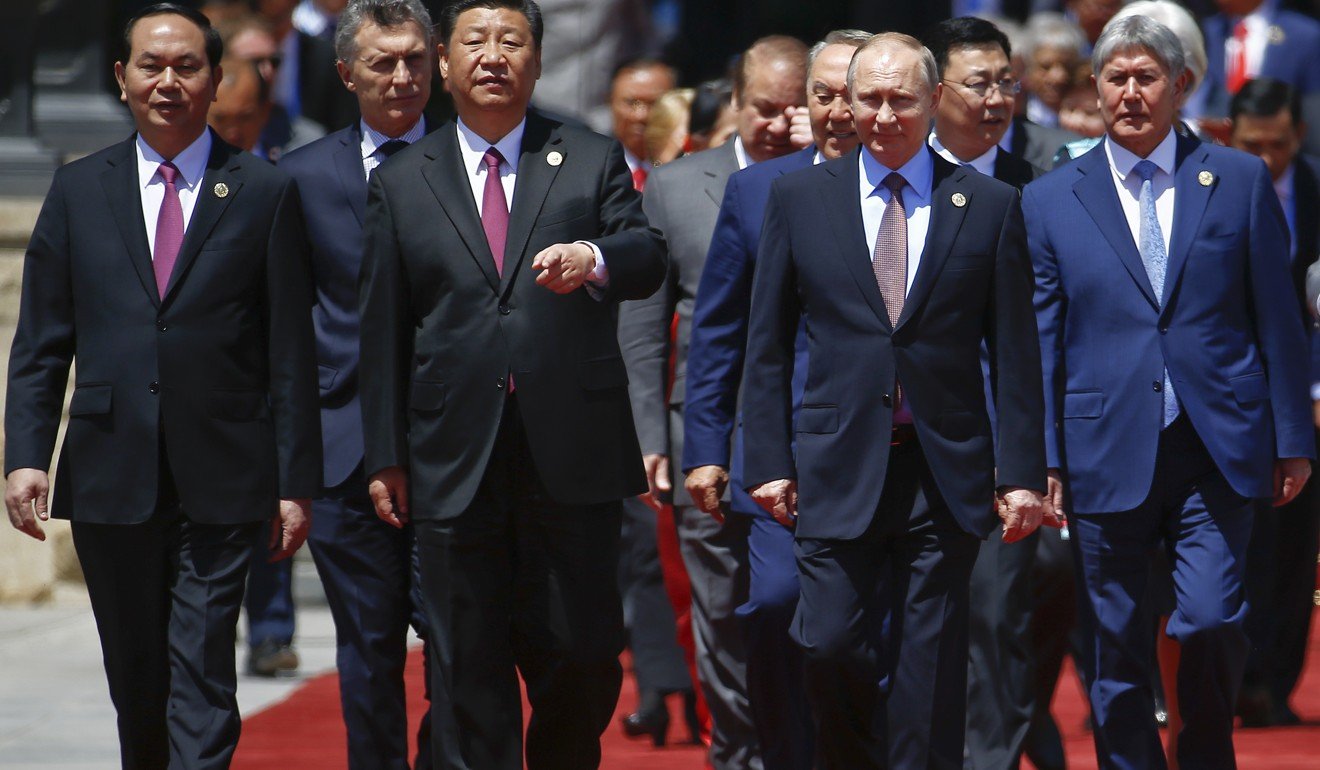

Touted as a modern-day Silk Road, the belt and road network would link China with Central Asia, South and Southeast Asia, Africa and Western Europe, through ports, roads, airports, pipelines and other infrastructure involving “65 countries, 29 per cent of global GDP, and 60 per cent of the world’s population”, as the Paulson Institute put in.

The goal, China says, is to promote efficiency in resource allocation and the “deep integration of markets”, raise standards of regional cooperation, and achieve “open, inclusive and balanced regional economic cooperation”.

Xi Jinping: Why I proposed the Belt and Road

The enormity of the undertaking, of course, gives rise to questions. While many countries along the belt and road are in desperate need of large-scale infrastructure investment, it is also true that there are a myriad other reasons for China to find these investments worth the attendant risks.

One reason is to diversify, and get better returns on China’s foreign exchange reserves, with infrastructure investments generating higher profit. Another is to provide relief for domestic overcapacity and zombie state-owned enterprises, particularly in the metals sector, as well as construction and materials.

But it is as much a matter of self-interest – part of China’s overall strategy of peripheral diplomacy – as it is about regional stability and development. As such, some argue that since these projects are motivated more by political factors than real economic rationale, there is a significant risk that they will fail to deliver the expected returns. Those concerns are not without merit.

‘Everything’s OK’: China hits back at IMF verdict on health of banking system

Ratings agency Fitch, for one, is sceptical: “Chinese banks do not have a track record of allocating resources efficiently at home, especially in relation to infrastructure projects.” As such, they are unlikely to have more success overseas. Meanwhile, local politicians, their families, and corrupt officials have an incentive to push white elephant projects, subordinating business logic to political and family agendas, and increasing the risks of unprofitable projects.

Fitch also estimates that the countries to which about US$900 billion in credit has been extended all run a high risk of default.

Belt and Road Initiative: what, when, why, how

Will Gwadar go the way of Hambantota? Why Chinese loans to Pakistan are sparking takeover fears

President Maithripala Sirisena, who unexpectedly defeated Rajapaksa in 2015, had campaigned on the promise to extricate Sri Lanka from China’s onerous debt terms. But, by then, the die had been cast. Exacerbating the issue was the fact that, having risen to middle-income status, Sri Lanka no longer qualified for concessionary loans and had to obtain commercial credit – where terms are guided by the markets.

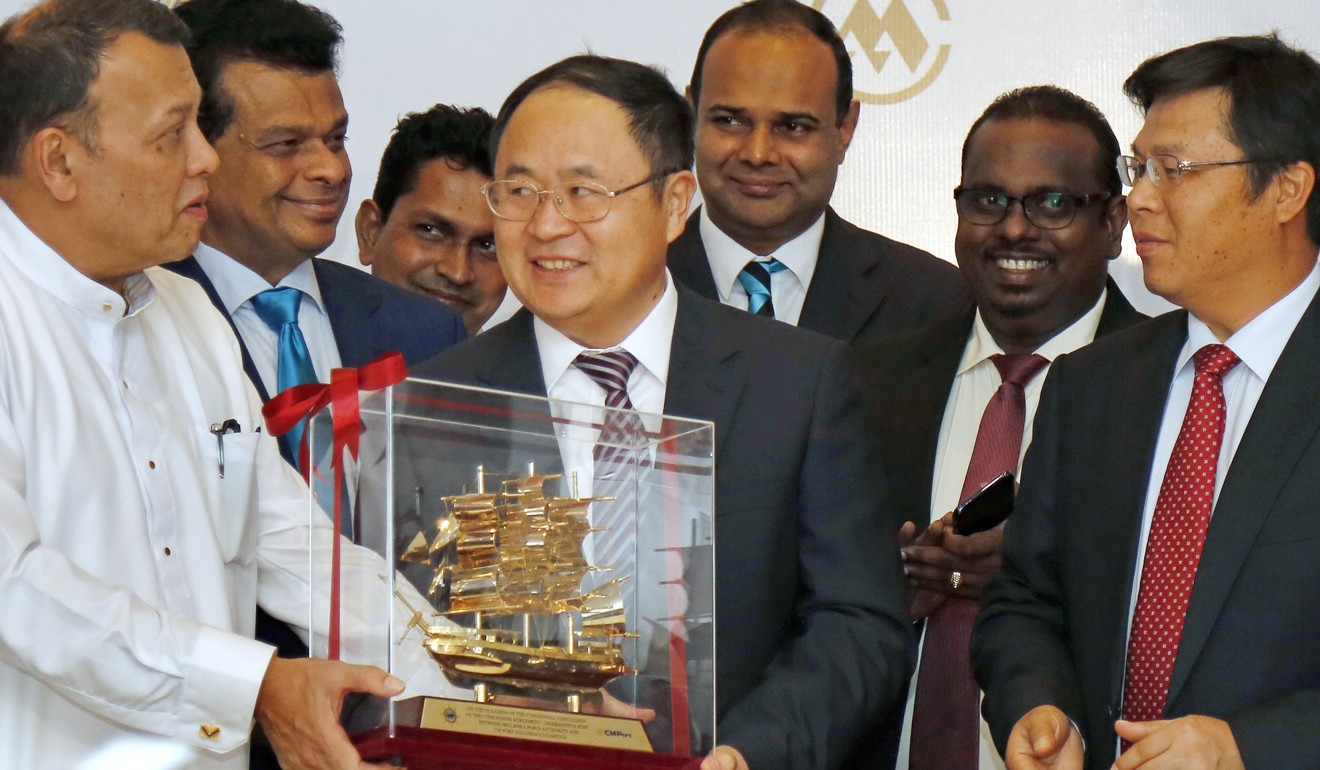

After suspending projects like the Colombo Port City, the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe coalition government tried to renegotiate the terms of servicing its debt, but was told unequivocally that the debt would not be written off. “But if you can’t pay,” the Chinese told Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, “we are ready to swap debt for equity.”

China to build Colombo CBD under ‘Belt and Road Initiative’

It’s no surprise that some observers call the belt and road ‘one road, one trap’

Many nations in the region are somewhere on the slope of a similar debt trap. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), Malaysia’s Forest City, Cambodia’s Sambor Dam and other projects, as well as countries like Bangladesh, Nepal, Indonesia and the Maldives, along with Ethiopia, Kenya and Venezuela, are all vulnerable to significant economic, political and environmental risks when they too readily accept Chinese money.

These moves suggest some of these countries are waking up to the fact that what appears to be Chinese largesse must be subjected to much greater scrutiny, lest they commit themselves to a Faustian deal.

Is an all-powerful Xi Jinping and an emboldened China good for Southeast Asia?

On the face of it, China does appear to be the lender of choice over multilateral institutions such as the IMF, World Bank or ADB – for not interfering in the domestic affairs of recipient countries, and a no-strings-attached approach. But there are, in fact, many unwritten but implied strings attached. And, as Sri Lanka has learnt, the consequences can be costly.

A Chinese flag flies over Sri Lanka as China extends its reach into India’s backyard

However, China views the situation quite differently. Liu Xiaoxu of the China Academy of Social Sciences writes, “China has no strategic illusion about Sri Lanka, which is too close to India geographically to resist any influence from its powerful northern neighbour, neither is there any deliberate or insidious plan to trick Sri Lanka into a debt trap. Nor is it economically naive to squander money building the largest swimming pool in a tiny island which is thousands of miles away.”

This clearly reveals the working of invisible hands by a very visible statecraft with a mission to create a “pacific” new world order mirroring the old tributary system.

Patrick Mendis, an associate-in-research at the Fairbank Centre for Chinese Studies, Harvard University, is the author of Peaceful War: How the Chinese Dream and the American Destiny Create a Pacific New World Order. Joey Wang is a defence analyst. Both are alumni of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard