Advertisement

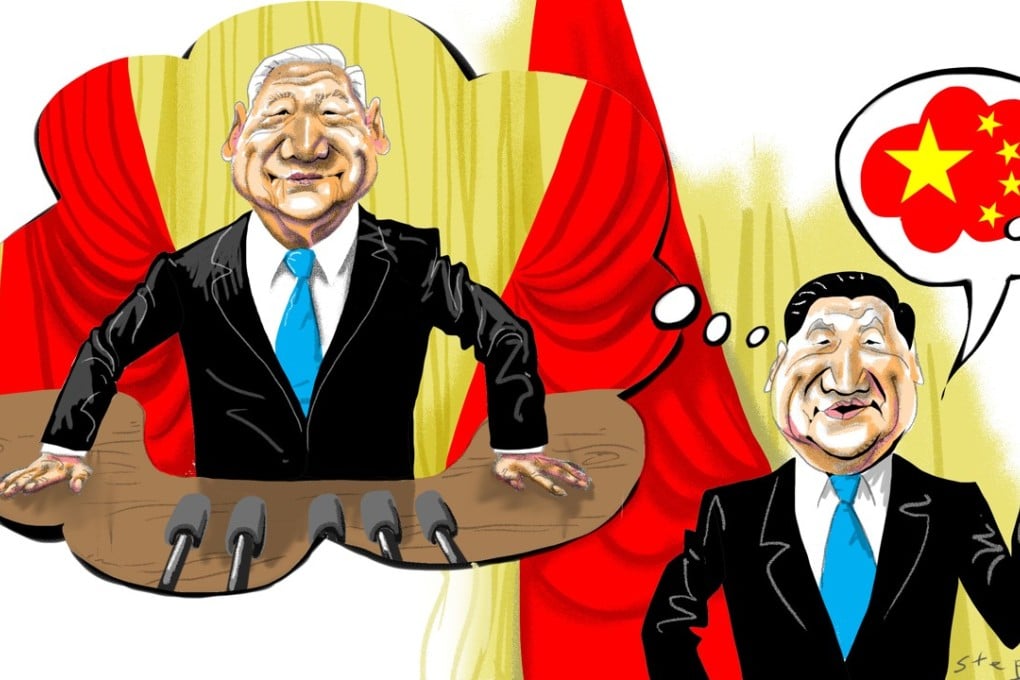

With an end to term limits, Xi can realise his Chinese dream – but will the price for China be too high?

Deng Yuwen says Xi Jinping may have good intentions for removing the rule limiting a president to two terms in office but, in the long run, society won’t be better off by overturning a decades-old institution put in place to prevent abuse of power

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Last Sunday, the Chinese Communist Party shocked the world by proposing to scrap the two-term limit for the Chinese presidency and vice-presidency, widely seen as a move to clear the way for Xi Jinping to retain power after 2023. The proposal is likely to be adopted later this month when the national legislature meets in Beijing.

Xi’s wish to stay on is no surprise – China watchers have speculated for months about his intent – but the timing of the announcement caught many off guard. Though the proposal was discussed in January at the party leaders’ second plenum, where revisions to the Chinese constitution were on the agenda, there was no word then of a discussion on term limits. The assumption was that the issue would not be raised at the “two sessions”.

More importantly, since the state presidency is more of a symbolic role in China’s political system, with real power vested in the party’s general secretary, the term limit is not considered a real obstacle had Xi wanted to remain president; he can get the relevant clause in the constitution amended at the 20th party congress in 2022.

Advertisement

Why, then, is he making the move now?

One educated guess is that it stems from his wish to realise the “Chinese dream” and bring about national rejuvenation during his term, to play a role in the history of the Communist Party – and of China – that is comparable to, and even exceeds, that of Mao Zedong’s.

Being immortal: inside Xi Jinping’s power play to reach the same status as Mao Zedong

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x