Advertisement

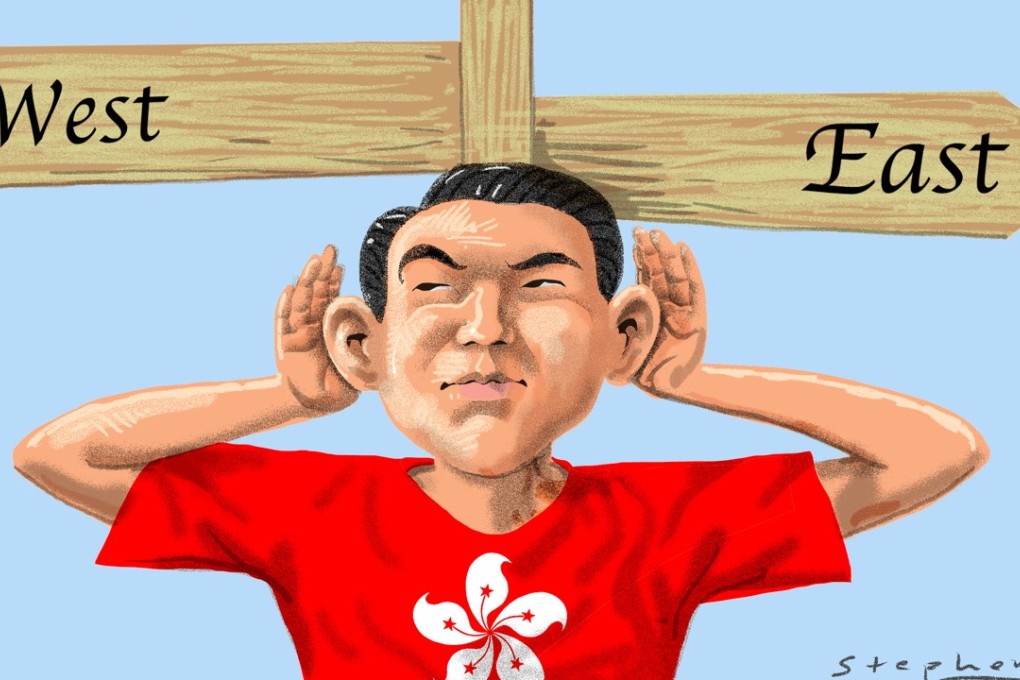

Hong Kong can best serve China through diplomacy – but first it must make its allegiances clear

Christine Loh says Hong Kong, having lived under competing ideologies for decades, is uniquely placed to serve as a mediator between China and the West

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Reassessment of Hong Kong’s relationship with the mainland is essential for the special administrative region to redefine its role at a time of seismic shifts in global affairs.

The shifts have much to do with the decision Beijing made some 40 years ago to reform and open up. China was mainly rural, among the poorest countries, technologically backward and disconnected from the world economy. Its fast-paced modernisation has become an important chapter in contemporary studies, as many countries wish to see what they can learn from it.

Hong Kong people remember many of the early reforms, the most significant of which was the setting up of special economic zones, starting with Shenzhen in 1980, the opening up of manufacturing, and China entering the World Trade Organisation in 2001. Other important changes included reforming state-owned enterprises, allowing private ownership, strengthening property rights, liberalising prices, reforming banks and taxes, etc. The 19th party congress last year announced many new reforms to expedite China’s development towards achieving “socialist modernisation” by 2035.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x