In a valiant attempt to assert the viability of the

“Lantau Tomorrow Vision” project, Development Secretary Michael Wong Wai-lun finally

divulged some numbers on March 19. The problem is that they don’t add up, or are based on dubious assumptions. And that’s extremely worrying for a project that’s the most expensive, complicated and risky in Hong Kong’s history.

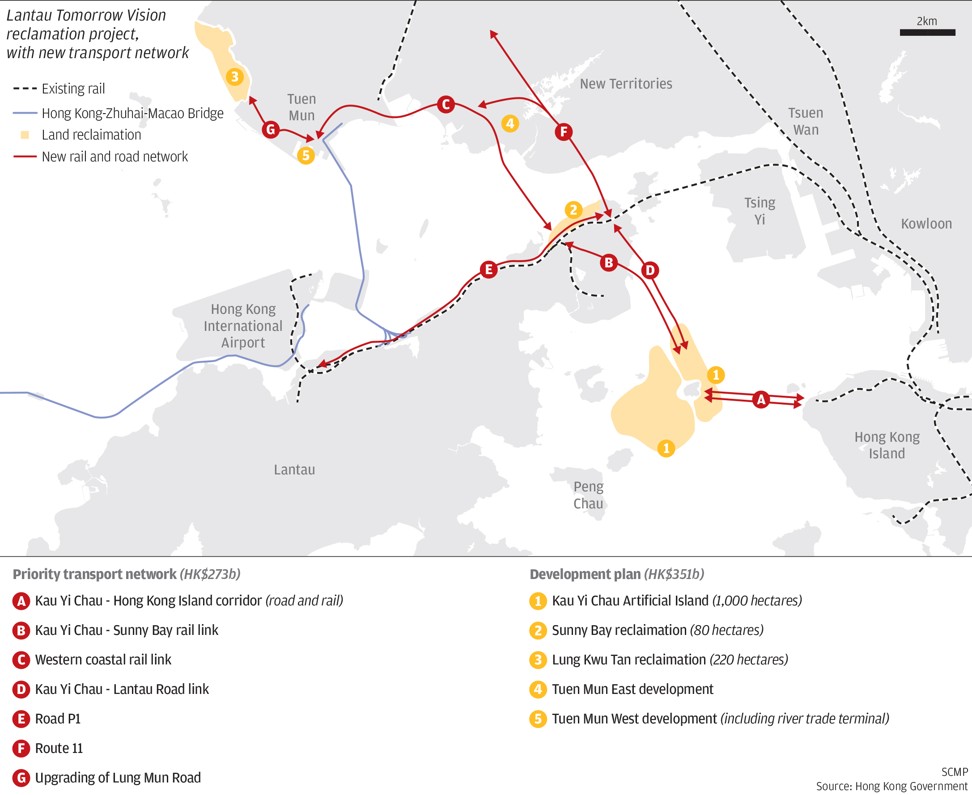

The initial phase of Lantau Tomorrow consists of creating 1,000 hectares of land around the island of Kau Yi Chau in the central waterway east of Lantau. On this reclaimed land will live 400,000 to 700,000 people, in 150,000 to 260,000 homes, 70 per cent of which will be public housing and 30 per cent private. It will also have a business district.

Wong said that, based on September 2018 cost data, the project, along with several smaller near-shore reclamation sites, will cost HK$624 billion (US$79.5 billion). Land designated for private housing and commercial development will be sold to developers,

yielding income of between HK$980 billion and HK$1.14 trillion, according to estimates by the Hong Kong Institute of Surveyors.

On the cost side, using the September 2018 cost data as a reference is misleading. Financing of infrastructure projects uses money-of-the-day methodology to reflect the actual cost incurred during the construction period, taking future inflation into account. (For example, the Shek Kwu Chau incinerator

approved in 2015 had a cost estimate of

HK$12.7 billion based on

September 2013 data but funding of

HK$19.2 billion was requested in 2014.)

The increase in construction costs over the past 10 years has averaged 4.7 per cent per year, according to the index published by the Civil Engineering and Development Department. So, using money-of-the-day methodology, the actual funding required in 2025, when construction is to begin, will be HK$1.1 trillion, not HK$624 billion.

On the income side, the government has adopted the Hong Kong Institute of Surveyors’

recommended sale price to developers of HK$10,000 to HK$12,000 per square foot for private housing units, the so-called accommodation value. The institute assumed the size of a private flat at 75 square metres (800 sq ft). Adding typical construction costs of HK$5,000 per sq ft, the cost alone to the developers for an 800 sq ft flat would be about HK$13 million. Adding 20 per cent profit would peg the price to about HK$15 million.

So Hongkongers who cannot afford a private flat now will find it even more unaffordable in Lantau Tomorrow. The government’s dilemma: either it sells the land at a high enough price to offset the cost of building Lantau Tomorrow, resulting in unaffordable housing, or it sells the land at a lower price, losing money but making housing more affordable.

Notice that the government is using as a benchmark a larger private flat size than the current average to boost the projected income from selling private land to developers. Similarly, it has inflated the area of land allocated for commercial development to boost income figures. Despite a shortfall of only

1 million sq m of Grade A office space, as forecast in the Hong Kong 2030+ plan, the government has used

4 million sq m to forecast the revenue from sale of land allocated for commercial development.

The 2030+ forecast was based on an annual gross domestic product growth rate of 2.5 per cent for Hong Kong and 4.5 per cent for Guangdong. Suggesting a fourfold increase in demand for commercial land is tantamount to assuming annual GDP growth of 10 per cent for Hong Kong and 18 per cent for Guangdong. While increasing the baseline to reflect a future economic upturn is reasonable, a fourfold increase is clearly contrived to enhance income figures.

Wong said that relocating residents from congested districts to Lantau Tomorrow will improve their quality of life. But 700,000 people living on 1,000 hectares equates to 70,000 people per sq km, making the new town more congested than Hong Kong’s most congested district, Kwun Tong, which has

57,000 people per sq km.

What’s more, these 700,000 people on Lantau Tomorrow will have only one tunnel connection to Hong Kong island. This lone tunnel will also handle the traffic from the northwest New Territories via a connection with the planned Route 11. For comparison, Sha Tin, with 660,000 people, has four major roads and three tunnels linking it to neighbouring communities. Whether the tunnel can carry such heavy traffic, how this traffic will affect Kennedy Town, where the tunnel will emerge and be directed to the rest of Hong Kong, is highly problematic.

Wong also claimed that Lantau Tomorrow would add

HK$141 billion per year to the Hong Kong economy, amounting to 5 per cent of current GDP. Given the 700,000 population, the per capita GDP of Lantau Tomorrow would be about HK$200,000. For the whole of Hong Kong, GDP per capita in 2018 was

HK$357,584, based on census data. So this game changer of a new town, costing HK$1.1 trillion, will be performing worse, economically, than Hong Kong at large now.

With Lantau Tomorrow, Hong Kong will have housing capacity for 9 million people. But the population will peak at

8.22 million in 2043, and decline to

7.72 million by 2066, according to the Census and Statistics Department. With the project, we will have excessive housing capacity, more unaffordable housing, and live in a more congested environment facing rising sea levels and traffic congestion. All for HK$1.1 trillion. Now that is an offer Hongkongers cannot refuse!

Tom Yam is a member of the Citizens Task Force on Land Resources, a group of professionals dedicated to broadening and facilitating the debate on critical issues including sustainable development, the optimal uses of land, and the conservation of resources