Let us hope that

the problems of the MTR Corporation do not reduce reliance on rail as key to urban transport. The MTR’s difficulties stem from two issues: the

pressure to fast-track the Sha Tin-Central and express rail lines after a decade-and-a-half of dithering over the former. Secondly, the confusion created by the 2000 listing of the MTR Corporation, making

a hermaphrodite out of what should have remained a wholly government-owned system integrated into transport planning.

But the MTR’s pains are minor compared with the policy mess on road use, where vested private-sector interests continue to stymie coherence and the use of electronics to manage and price road usage.

Let’s start with the taxis. Yes, Uber and the like have been disrupters, which can make life uncomfortable for those being disrupted. But is that not what is supposed to happen in economies not run by luddites? Most other industries, not least the media, have been drastically disrupted by technological change. So what is so special about taxis?

The answer, of course, goes back well before Uber’s appearance. It is the determination of government to

protect the interests of an unworthy bunch of rentier capitalists who own the taxi (and minibus) licences. Only the government can explain why they are so influential. Scarcity has driven the price of licences up to between HK$6 million (US$760,000) and HK$7 million. Meanwhile, taxi drivers – almost all of whom rent their vehicles – have to fight hard for income. The result: antiquated vehicles and often aggressive drivers.

The answer is simple: ramp up the supply of licences. Increase the urban number by 40 per cent to 21,000 but with new ones paying an annual fee calculated as a percentage of notional income. This will open up the trade for drivers to acquire their own, new vehicles. That alone would modernise the fleet and make owner-drivers proud of their cars and service. All licensed taxis would have the choice of operating either under a fixed-rate system as currently applies, or on an Uber-type system with pricing determined on a case-by-case basis.

Any claim that more licences would lead to more road congestion is nonsense in a situation where

private-car numbers have risen from 338,000 at the end of 2003 to

618,000 today while taxi numbers have been almost static. There is no particular reason to penalise ownership of vehicles but two things do matter: the price of roads and tunnels, which reflect cost and land use, and avoidance of congestion caused by illegal stopping and parking.

The indulgent attitude of the police towards

chauffeur-driven vehicles waiting to pick up bosses says much about how Hong Kong’s elite has inherited colonialist assumptions. But police work would be a fraction less time-consuming by simply applying camera-based fines to parking, as has long been the case with speeding, and

making fines meaningful to owners of HK$1 million cars.

Hong Kong is promised a

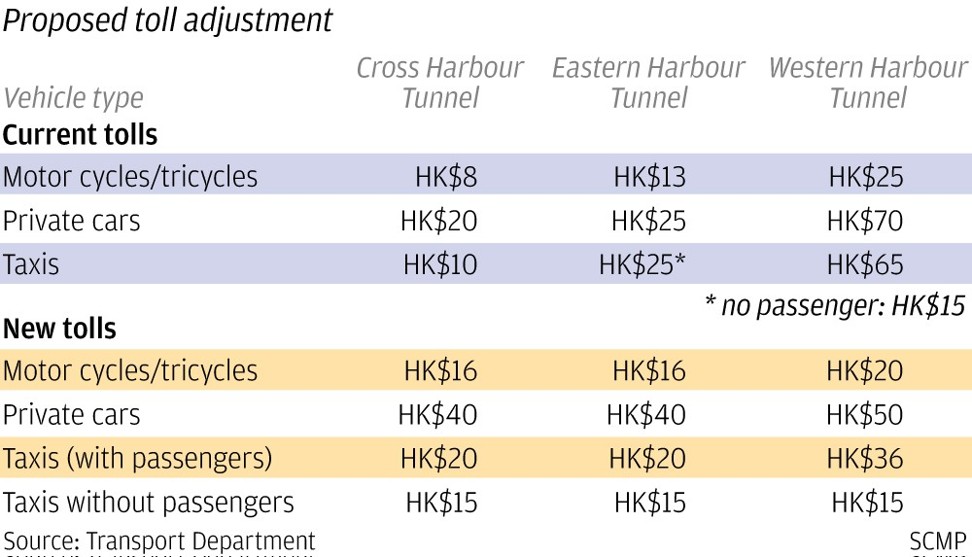

road-pricing scheme eventually but the vested interests have long resisted what would be a huge benefit to the vast majority – public transport users. Singapore has had one since 1975 and an electronic one since 1998. Tolls here are applied haphazardly to some tunnels/links but pricing is random, thanks in part to conflict between public and private interests. Why did the government, bursting with excess capital, give the Tai Lam Tunnel project to a private company, Sun Hung Kai Properties?

That tunnel, which cost

HK$7.25 billion to build, now charges

HK$48 for a car while the

HK$36 billion government-owned Central-Wan Chai tunnel costs nothing! Why? Is it so as not to inconvenience the senior civil servants and bankers who are its main beneficiaries? Toll collection is antiquated everywhere, as well as illogical, making it impossible to vary pricing according to time. Sydney, a city comparable in size and number of toll roads and tunnels, has for some years had a single electronic pricing system for them.

Here government officials give endless speeches about information and technology but do little to use them. Even parking in central Hong Kong in no way reflects land prices. Indeed, it is a steal compared with equivalents in Sydney, London, New York, etc.

It does not, of course, help that legislators, including most of the pan-democrats,

oppose toll increases for private cars even though these are regularly used by only a tiny proportion of the population.

At the root of the issue is that the upper bureaucracy is at least as addicted to private transport, preferably with a driver, as the business elite, when it should be setting an example. If the definition of a developed society is one where rich people take public transport, Hong Kong remains backward, socially as well as technologically.

Philip Bowring is a Hong Kong-based journalist and commentator