China is risking economic stagnation with its half-hearted stimulus measures

- China must not allow its GDP growth rate to fall below 6 per cent, or the economy may be stuck on a low-growth track

- Policymakers should step up investments, splash out on needed infrastructure and be generous with both fiscal spending and monetary easing

If policymakers do not implement the necessary countermeasures now, the economy could get stuck on a track of lower growth.

What kind of policy measures could help China stabilise its economic growth at 6 per cent or above for a few years from 2020? In another words, how could we prevent China’s L-shaped slowdown from declining further?

Clearly, investment has played an essential role in developing China’s economy, and it should continue to do so, not necessarily in real estate, but in infrastructure and other sectors that need a boost.

Second, China’s infrastructure is far from mature. For example, the tap water in many areas, even in major cities, still does not meet the drinkable water standards recognised by the World Health Organisation.

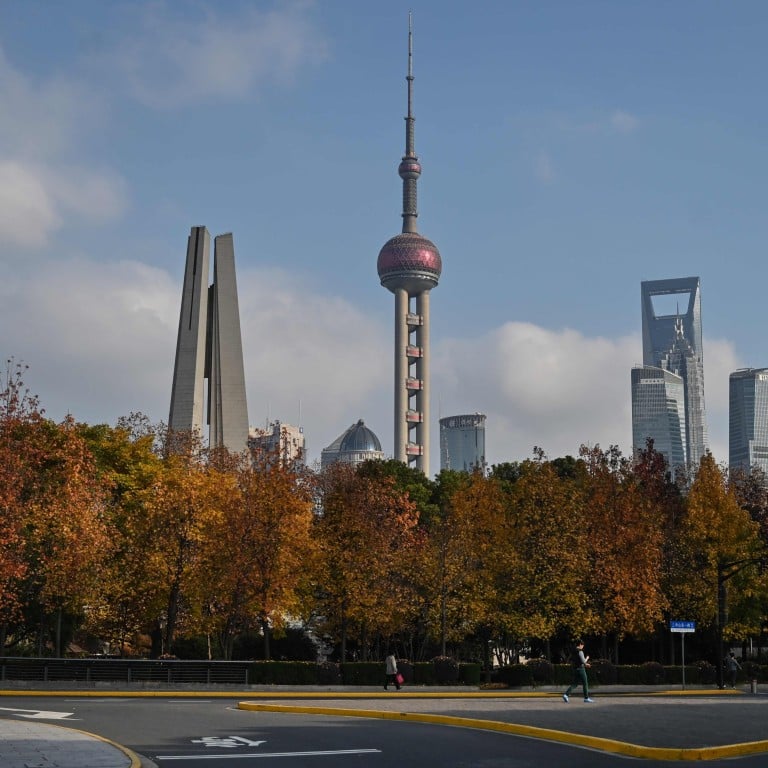

Shanghai, which plans to complete the reconstruction and repair of its water pipe network by 2030 to raise the quality of its tap water, has invested about 15 billion yuan (US$2.14 billion) this year alone on major water supply projects. If the central government sets a goal for the whole country to have drinkable tap water, this would probably require 1 trillion yuan in investment, as shown by the experience of Shanghai.

Third, China can continue to increase fiscal spending. One reason for the slower investments, especially infrastructure investment, is that some local governments lack funds. The central government should further increase fiscal spending.

Is China serious about cracking down on its mountain of debt?

As Professor Yu Yongding of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences pointed out, past experience shows that a better way to deleverage is to raise the GDP growth rate, rather than to cut loans to enterprises, which may cause more problems than it solves. Therefore, increasing government debt and expanding fiscal spending at both the local and central levels would be a safe option to further stimulate the economy.

Lastly, China can adopt ultra-low interest rates and more quantitative easing when needed. After the global financial crisis in 2008, the US, the EU and Japan implemented ultra-low rates and QE, which has lasted nearly a decade. Comparatively, during the same period, China’s interest rates were much higher, so enterprises and households were bearing higher costs.

To conclude, taking serious policy action once economic growth declines to 5 per cent might be a poor choice for China. What would happen if policy measures do not work effectively at that time? Would that lead to an even lower growth rate? If so, many financial indicators would worsen, and the economic situation might be difficult to control.

China should not allow its growth to slow to below 6 per cent in 2020 and perhaps into the next few years.

G. Bin Zhao is a senior economist at PricewaterhouseCoopers China and he also leads the firm’s China Strategic Research. This article was inspired by a seminar discussion with Professor Yu Yongding. The opinions expressed here are the author’s own