Mao Zedong thought Japan did the Communist Party a great favour by invading China. Can Hong Kong agree with that?

- The Chinese leader believed his party could not have come to power if the Japanese had not invaded. Hong Kong’s education secretary, in framing the issue about the DSE exam question as one of political correctness, is missing the point

Surprisingly, Mao told him there was no need to apologise. Japan, Mao said, had done the Communist Party a great favour.

“We must express our gratitude to Japan,” Mao said. “If Japan didn’t invade China, we could have never achieved the cooperation between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party. We could have never developed and eventually taken political power for ourselves. It is due to Japan’s help that we are able to meet here in Beijing.”

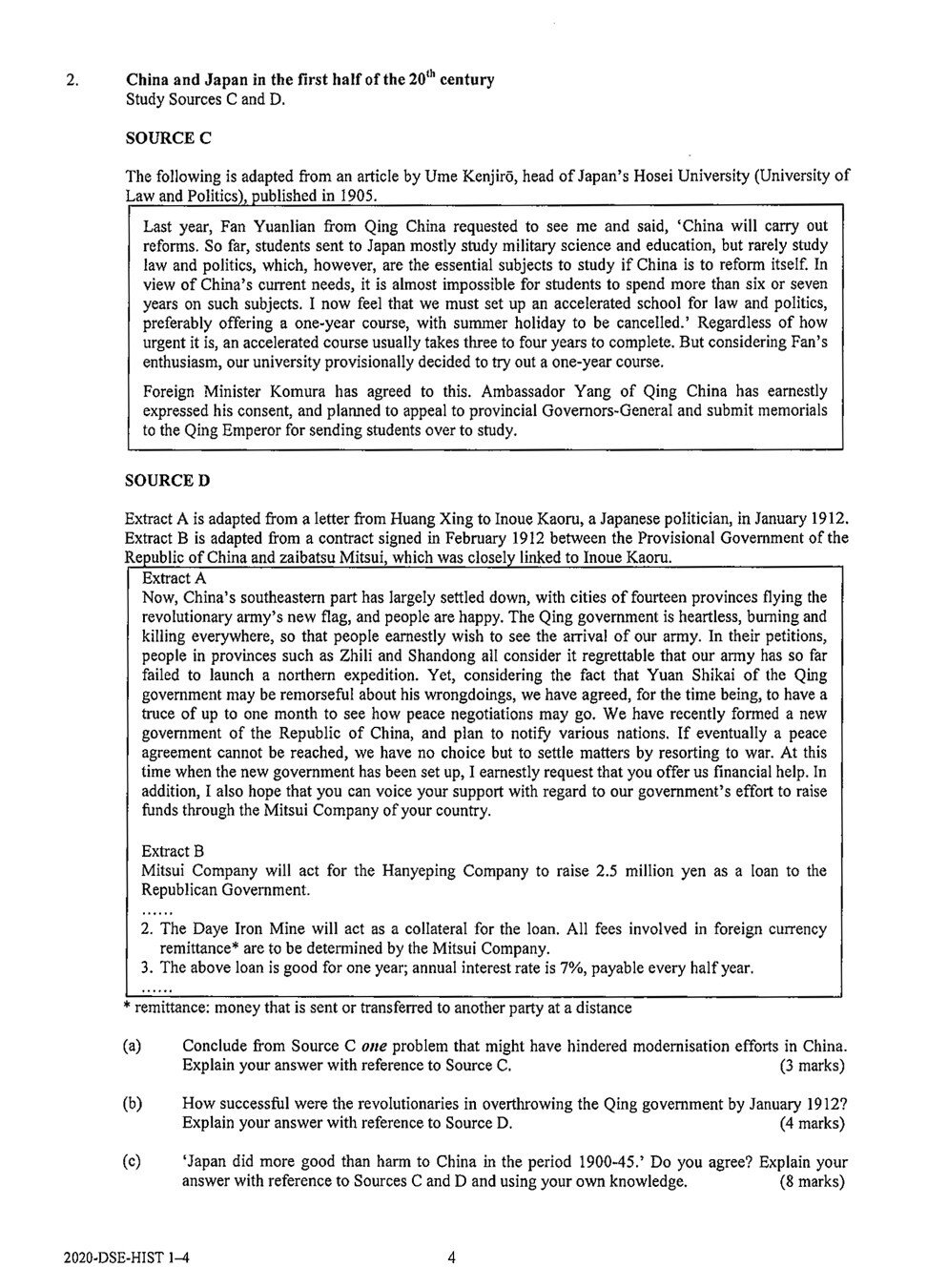

How a Hong Kong history exam question stirred up controversy

All these were consequences of Japan’s invasion. Whether communist control of the mainland is good or bad is another issue but, according to Hong Kong’s secretary for education, what Japan did was harmful, with no redeeming quality.

Mao’s analysis has been confirmed by one of the foremost historians today, Steve Tsang, director of SOAS China Institute, who wrote in 2015 that Chiang’s decision to confront Japanese aggression “dramatically changed the fortune of the exhausted and heavily depleted CCP (Chinese Communist Party) struggling to survive in the poor northwest of China”. It was a “turning point” for the communist forces.

Tsang said: “Whether the CCP could otherwise have survived Chiang’s ‘final push’ in his extermination campaign cannot be known.” But Mao evidently believed that the communists would have lost and, as he put it, would not have been in power in 1972.

Surely, in view of Mao’s analysis, Yeung’s stance – that no good has come of the Japanese aggression – suggests it is a bad thing for the communists to have won the civil war, established the People’s Republic of China, and to be controlling China today, since all these flow from the Japanese invasion.

It may well be argued that the history question was too sophisticated for secondary school students, though not university students. But this is not the argument the secretary for education made. He seems to see the issue as one of political correctness, which surely is not what education should be about.

When the Cultural Revolution spilled over into riots in Hong Kong – and changed lives forever

There is no reason to think that just because students were provided with passages from the early 20th century, they would forget what they knew about the Japanese invasion in the later decades. The question was clearly designed to test students, and a sampling of answers would reveal whether they applied critical thinking and assessed both the positive and negative aspects of the Japanese actions.

A check will show whether Hong Kong students are capable of independent thinking or whether they are gullible, believing whatever they are told, regardless of what they know to be true.

Frank Ching is a Hong Kong-based writer and commentator. Follow him on Twitter

Help us understand what you are interested in so that we can improve SCMP and provide a better experience for you. We would like to invite you to take this five-minute survey on how you engage with SCMP and the news.