South China Sea: If US spy planes were posing as airliners, it must explain why

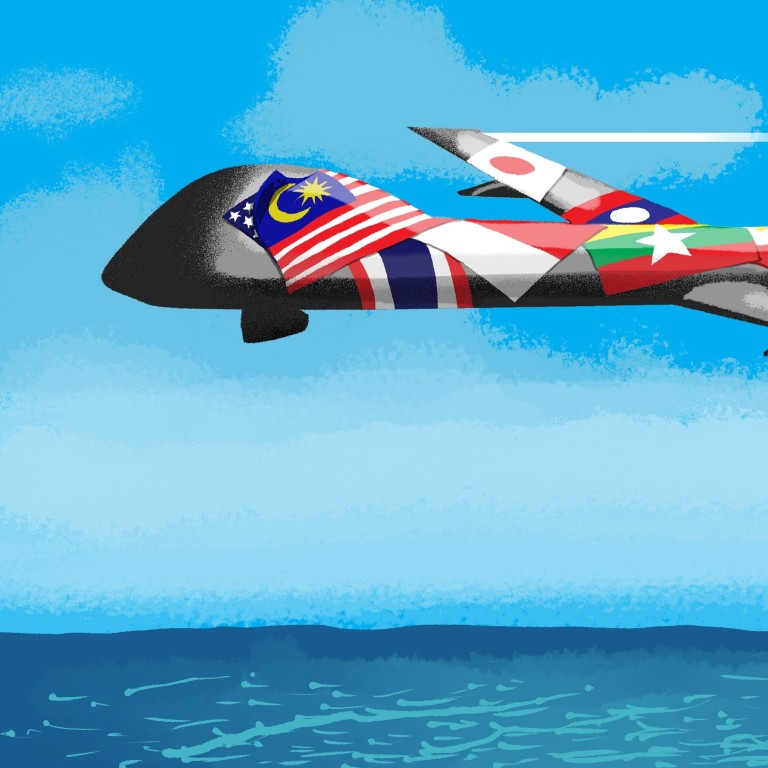

- Using a false civilian cover for spy planes may not be illegal but is dangerous and risks a major international incident. On this and undersea drones, the US owes the world more than studied silence

Some allege that such purposeful impersonation violates the Convention on International Civil Aviation. All planes registered with the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) are assigned a unique six-digit code which is automatically transmitted by their transponders when interrogated by air traffic control radar. This mainly ensures that planes maintain minimum separation.

In response to the allegation, General Kenneth Wilsbach, head of Pacific Air Forces, said: “I know we follow the rules for international airspace.”

02:32

Washington’s hardened position on Beijing’s claims in South China Sea heightens US-China tensions

US Air Force Boeing RC-135W and E-8C intelligence collection planes have frames similar to the Boeing 707-200 civilian airliner, and sometimes follow commercial air routes. Their identification code is what helps to distinguish them on remote sensors.

When China spots a spy plane, its military assets probably go silent. But with a “false flag”, the spy plane may deceive them into continuing activity and communications can be monitored. Under international norms, civilian aircraft should not be shot. The US may be betting on this, ironically taking advantage of China’s adherence to international norms.

South China Sea: the dispute that could start a military conflict

The US response is to prepare to cripple China’s command, control, communications and computers, and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) systems. This means ISR is the “tip of the spear” and both sides are trying to dominate this sphere over, on and under China’s near seas.

00:47

A rare at-sea look at China’s aircraft carrier the Liaoning and fighter jet training

China has long disagreed with US ISR probes in the South China Sea. Both countries also disagree over the regime of prior permission for marine scientific research in China’s exclusive economic zone as stipulated in UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

China accuses the US of violating that regime by deploying instruments without its consent to search for and track submarines in its exclusive economic zone. But the US holds that such activities are military surveys and thus exempt from consent.

Critics also claim this practice is an “abuse of rights” prohibited by UNCLOS. In sum, these US actions constitute a violation of the UNCLOS-mandated duty to pay due regard to the rights of coastal states.

The US places a heavy emphasis on developing aerial, surface and underwater drones for missions that include ISR. Years ago, it was already deploying in the South China Sea “new undersea drones in multiple sizes and diverse payloads that can, importantly, operate in shallow water, where manned submersibles cannot”, according to then defence secretary Ashton Carter.

How the US, not China, is endangering peace in the South China Sea

But UNCLOS requires that submarines – presumably including drones – operating within 12 nautical miles of a coastal state must surface and show their flag. Little detail is publicly known of the capabilities, missions and deployment of these drones and their adherence to international law and norms is questionable.

Rather than the studied silence from the US, the world needs a full explanation of these practices and how they do not infringe upon international laws and norms.

Until then, US demands that China uphold the international order ring hollow. Indeed, the US may not only be violating international norms but also setting the stage for a major international incident.

Mark J. Valencia is an adjunct senior scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou, China