Hong Kong is stuck in a high land price trap. Qing dynasty China holds many lessons

- In the late Qing dynasty, with its highly developed farming economy, there was no incentive to innovate to meet the needs of the burgeoning population

- Hong Kong, faced with increased demand for housing, persists in pursuing a high land price policy instead of thinking out of the box

By many accounts, China’s economy during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) was the largest in the world. Political scientist Samuel Huntington estimated that China accounted for almost a third of the world’s manufacturing output in 1750, but its share then declined steadily.

China in the late imperial period was not closed to the Western world. Many Western inventions, such as cannons, handguns, clocks, telescopes and microscopes, were imported and successfully imitated. Yet the scientific and industrial revolutions which transformed the means of production in the West swept past China without creating any impetus for technological revolution.

The “great divergence” in China’s economic performance from that of its European counterparts during this period has been the subject of many scholarly inquiries. Historian Mark Elvin concluded that China missed the opportunity for an industrial revolution because it was caught in a “high-level equilibrium trap”.

By the late Qing dynasty, China’s farming economy had become highly developed. But labour had become so abundant (the population in 1850 reached over 400 million), improvements in traditional farming and transportation technologies had reached their limits, and additional resources (land and labour) were unable to support higher crop output on a per mou (0.165 acre) basis.

As a result, farmers had no incentives to adopt new, disruptive technologies to boost output. China became trapped in a pattern of “quantitative growth” but also “qualitative standstill”.

Many analogies can be drawn between the late Qing situation and Hong Kong’s predicament.

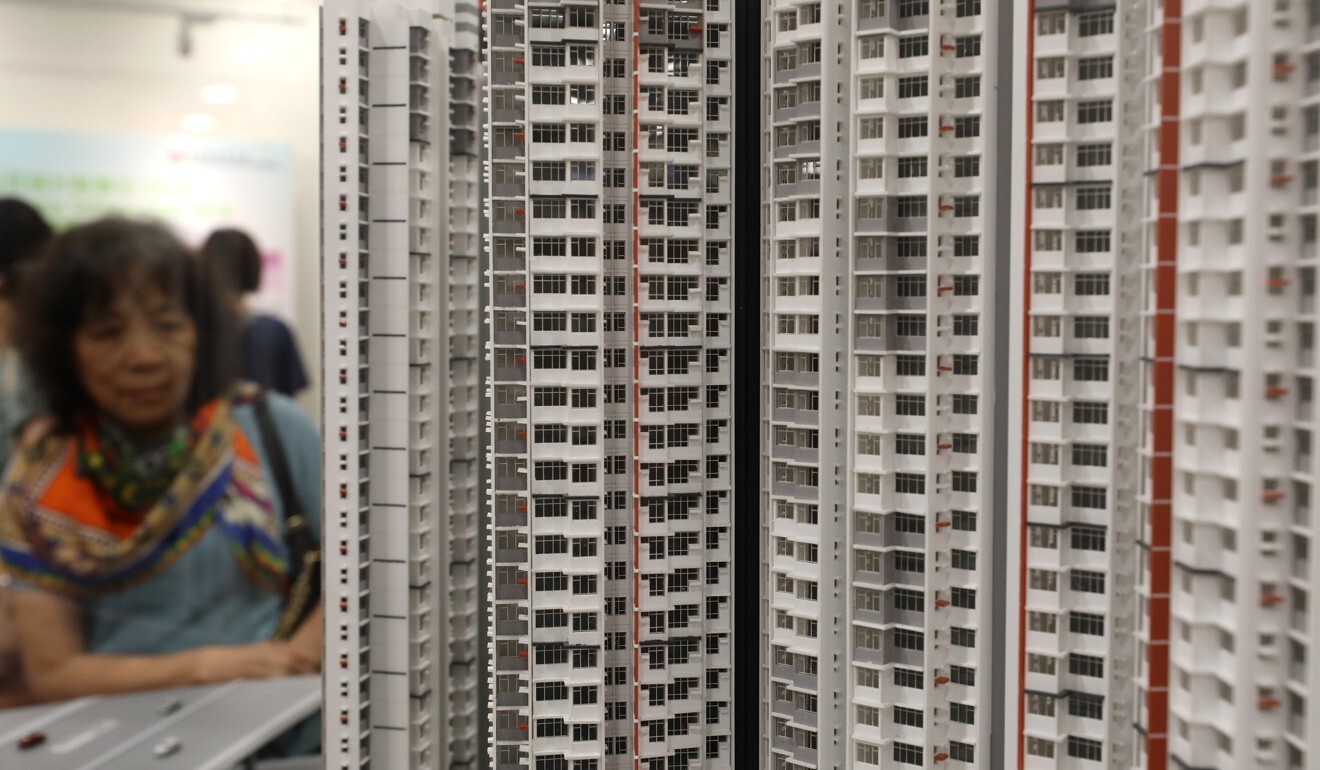

With demand rapidly outstripping supply, Hong Kong’s developers have tailored their products to meet demand from different market segments, ranging from younger, local homebuyers getting help from parents to wealthy mainland Chinese willing to spend hundreds of millions on trophy homes.

04:29

Hong Kong cage home resident finds space too small for self-quarantine amid coronavirus outbreak

Hong Kong developers cool to converting private reserves into land for housing

Despite these measures, property prices continued to hold firm and brisk transactions generated phenomenal fiscal surpluses for the government. From 2011-12 to 2018-19, the government’s cumulative fiscal surplus amounted to HK$575.2 billion (US$74.2 billion). Revenue arising from land/property sales (land premiums and stamp duties from property transactions) totalled HK$1.066 trillion, or 26 per cent of total revenue.

In so doing, Lam was following a pattern of public finance management well established by her predecessors – using land revenue to finance welfare or economic development. Colonial officials knew full well that Her Majesty’s Treasury could not come to their rescue if the colony’s budget showed any red ink.

Behind the much vaunted “small government, big market” economic doctrine was a deep-seated reluctance to rely on deficit financing or debt to boost growth or meet welfare demands. Revenue from land provided the best solution for the government’s financing needs. But it means that, for more than 170 years, the Hong Kong government, despite its denials, had to pursue a “high land price” policy.

How Hong Kong politics help fuel city’s ever-rising property prices

02:43

Why Carrie Lam’s Lantau land reclamation plan is so controversial

But that would mean Hong Kong people would forever be doomed to pay sky-high sums for tiny homes. If sizeable land supply could not be produced quickly and at a much cheaper cost, Hong Kong people would forever be caught in the “high land price” trap, and anger would boil over.

Our “high land price” policy has created a highly developed and profitable property sector, and assured the government of buoyant revenue (most of the time). But that has taken away the incentives for the government and the private sector to innovate. Hong Kong can hardly be said to be at the forefront of innovation among Asian economies.

Our future will be bleak if we cannot think out of the box, and break out of the Hong Kong version of a “high-level equilibrium trap”.

Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee is a lawmaker and chairwoman of the New People’s Party