US Federal Reserve must get creative and act fast to end inflation spiral

- Despite the flashing warning signs, the Fed remains wedded to a monetary policy born of the low-inflation past

- With inflationary pressures going from transitory to pervasive, the policy rate should be the first line of defence

In doing so, the Fed indicated it was prepared to forgive above-target inflation to compensate for years of below-target inflation. Little did it know what it was getting into.

In theory, average inflation targeting made sense – an arithmetic consistency of undershoots balanced by overshoots. In practice, it was an inherently backward-looking approach, conditioned by a long experience with slow growth and low inflation.

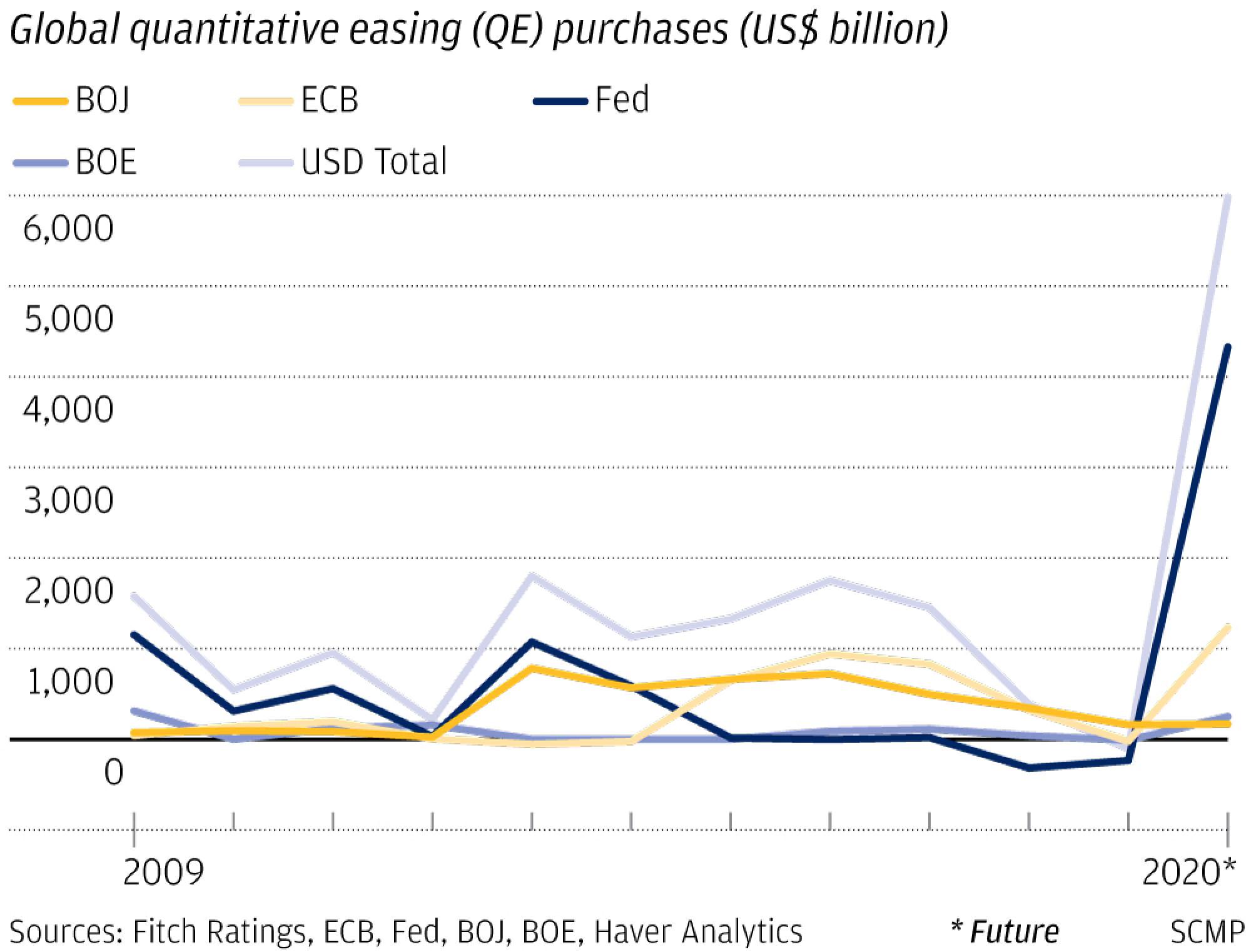

Like many, the Fed believed the pandemic shock of early 2020 was similar to the 2008 global financial crisis, underscoring the possibility of another anaemic recovery that could push already-low inflation dangerously towards deflation.

Those concerns are understandable if a crisis hits when inflation is already close to zero. But, by fixating on such risks, the Fed all but ignored the possibility of major upside inflation.

Today’s price and cost pressures are too numerous to count. Transitory one-off price adjustments became pervasive, and a major inflation shock is at hand.

But when reality came close to the hypothetical in 2009, Bernanke’s script became an action plan – as it did again during the Covid-19 shock of 2020. While out of basis points at the zero bound, the ever-creative Fed was never out of ammunition.

The Fed faces two complications. First, unwinding ultra-accommodative monetary policies is a delicate operation that raises the possibility of corrections in asset markets and the asset-dependent real economy.

Next move for China’s interest rates should be up, not down

Second, there is confusion over how long it takes to return policy to its pre-crisis settings. That is because, until now, there has never been an urgency to normalise.

While that might be appropriate in a low-inflation environment, an inflation shock makes it unworkable. The preferred first step is likely to have only a limited impact on the real economy and inflation.

The Fed needs to reassess its approach to policy sequencing. With inflationary pressures going from transitory to pervasive, the policy rate should be the first line of defence.

The federal funds rate is at minus 6 per cent in inflation-adjusted terms, deeper in negative territory than in the mid-1970s. My advice: up the ante on creative thinking. With inflation surging, stop defending a bad forecast and forget about tinkering with the balance sheet.

Get on with the heavy lifting of raising interest rates before it is too late. Independent central bankers can afford to ignore the political backlash. I only wish the rest of us could do the same.