Ageing Asia needs immigration reform to end care worker shortage

- Asian countries in need of long-term carers cannot meet the growing demand through domestic recruitment alone

- Multi-year visas, emigration that benefits countries of origin and regional collaboration can all help ensure proper care

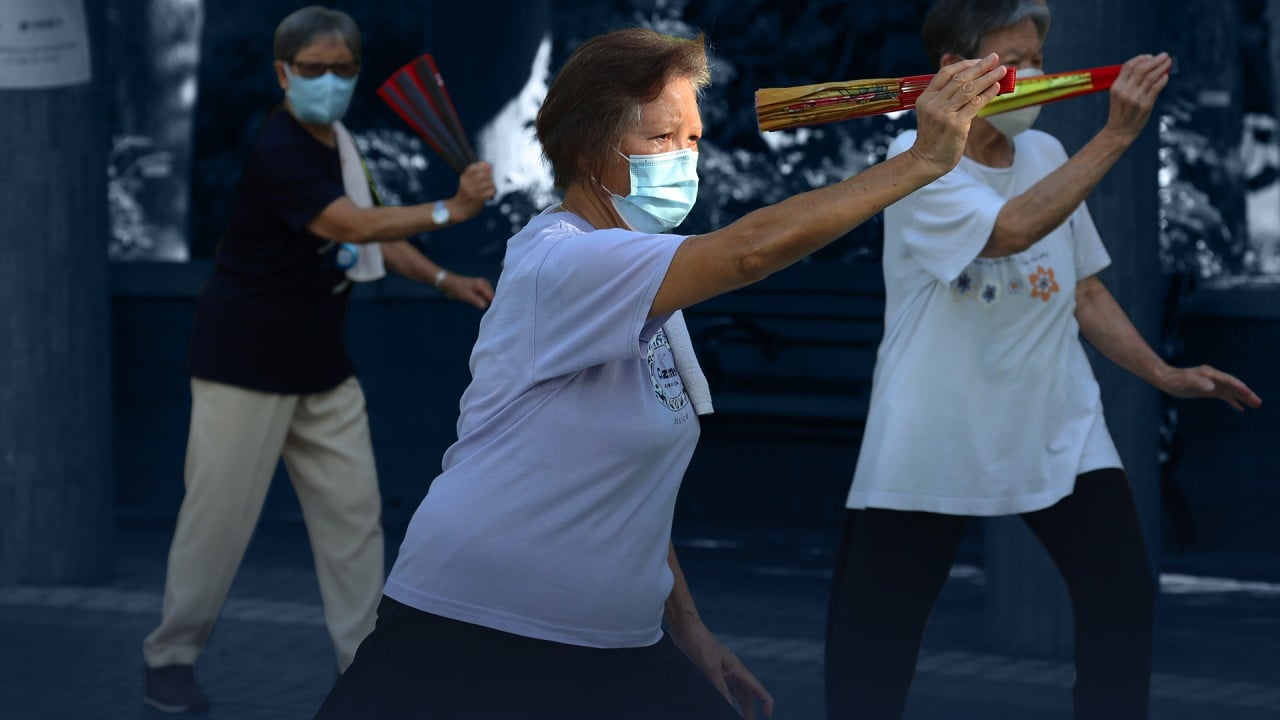

For example, in 1960, the average life expectancy in China was just 44. By 2060, it is expected to reach 83. These older people have more complex conditions, leading to a greater need for long-term care.

Today, the Asia-Pacific region lacks 8.2 million care workers. In China, it is estimated there is just one formal long-term care worker per 100 older people, compared to the global recommendation of at least four.

Whether it is because of the wages and working conditions offered, perception and status of those who work as carers or true labour scarcity, the demand for long-term care in Asia is not being met through local recruitment.

Singapore admits care workers through the work permit and S Pass schemes. Taiwan has been handing out three-year visas to live-in carers since 1992.

But these efforts are not enough to meet the vast shortages that exist now and are predicted to increase. Countries throughout the region, including China, should reform their immigration policies to make it easier for care workers to migrate.

How can this be done? First, destination countries for migrants should create multi-year visas for care work. They should not be restricted to a specific employer but could be restricted to a certain region or the healthcare sector in general.

Migrants are a help to Hong Kong’s ageing society, not a hindrance

Health ministries on both sides should work together, learning lessons from trailblazers in this field such as the Philippines.

Third, regional collaboration is key. Asian governments, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the World Health Organization and the Asian Development Bank must all work together to tackle this issue.

The entire region is ageing; countries of origin will need their own migrant care workers in the decades to come. All policy actors therefore need to come together to work on regional solutions, including recognition of skills and qualifications, and harmonisation, to ensure all Asia’s older people receive the care they need.

If Asia is to care appropriately for its millions of extra older people, it will need millions of new care workers. While countries should improve wages and working conditions to make the sector more attractive to locals, expanded immigration will also be required.

Helen Dempster is the assistant director for the Migration, Displacement, and Humanitarian Policy Programme at the Centre for Global Development