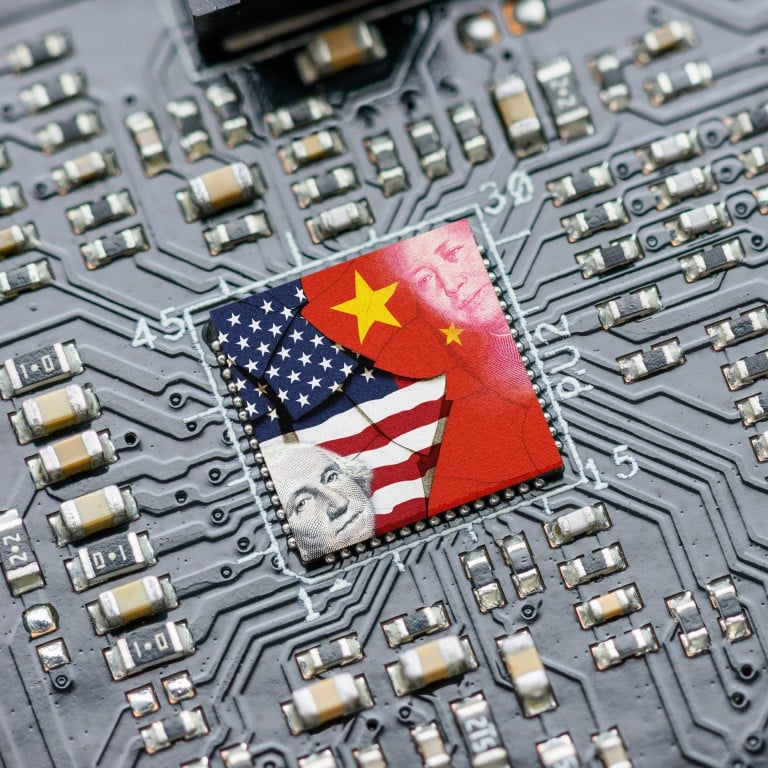

Why an accelerated US-China tech decoupling is truly worrying

- A blanket ban on products that use US technology being sold to China would not just affect China’s tech development and hurt US companies with Chinese business

- It would also rip up global tech supply chains, leaving the world economy with higher inflation and slower growth

The stated US intention is to prevent sensitive technology with military applications from being acquired by China. However, the latest move – which US officials said was necessary to stop China from becoming an economic and military menace – threatens a significant spillover into non-military applications.

Much uncertainty still surrounds the scale of implementation, but if strictly followed through, the announced measures could effectively sanction China’s access to critical inputs for its technological, economic and social development, with far-reaching ramifications.

For example, would other countries be liable if their products sold to China involve US technology? A blanket ban, enforced on a global scale, would have a significant impact on China’s tech development, with material ripple effects on its manufacturing and export sectors.

The latest developments will also affect the global production of and trade in tech products. The proliferation of global tech supply chains has been the backbone of globalisation, manifested in the creation of multi-country production networks and increased international trade cooperation.

For the US itself, the implementation will not come without economic costs. Home to some of the world’s largest chip makers, the US is the world’s pre-eminent source of advanced semiconductor technology, even though production of these chips has long shifted offshore (to Taiwan, South Korea and Japan).

Semiconductors now at the heart of US-China power struggle

China is the biggest customer of US chips, and sales to China can amount to up to 60 per cent of revenues for companies such as Qualcomm, Texas Instruments and Intel Corp. Strictly enforcing the chip ban could, therefore, inflict pain back on the US by inhibiting the growth of its own companies.

Furthermore, for those who make consumer products that rely on US technology (for example, smartphones, electric vehicles and sophisticated electronics), moving operations out of China – if that is ultimately required – would take time and incur costs. The latter would eventually be passed on to consumers, adding to inflation pressures. Higher inflation and slower growth could be the general consequence of a fragmenting global economy in the years ahead.

The ramifications of an accelerated tech decoupling between China and the US are truly worrying. While the scale of implementation of the ban remains unknown, it’s fair to say that markets are not yet pricing in a worst-case scenario of a strict and blanket ban, enforced on a global scale.

As we move into US election season with the impending midterm elections, commentary could escalate further – although over the longer term, there remains scope for resistance from Silicon Valley to temper implementation.

However, this remains a further ratcheting higher of US-China tensions in what is already a geopolitically and economically unsettling world. It serves as a reminder that, besides the Ukraine war, there are plenty of other geopolitical risks for the global economy and financial markets to consider.

Aidan Yao is senior emerging Asia economist at AXA Investment Managers