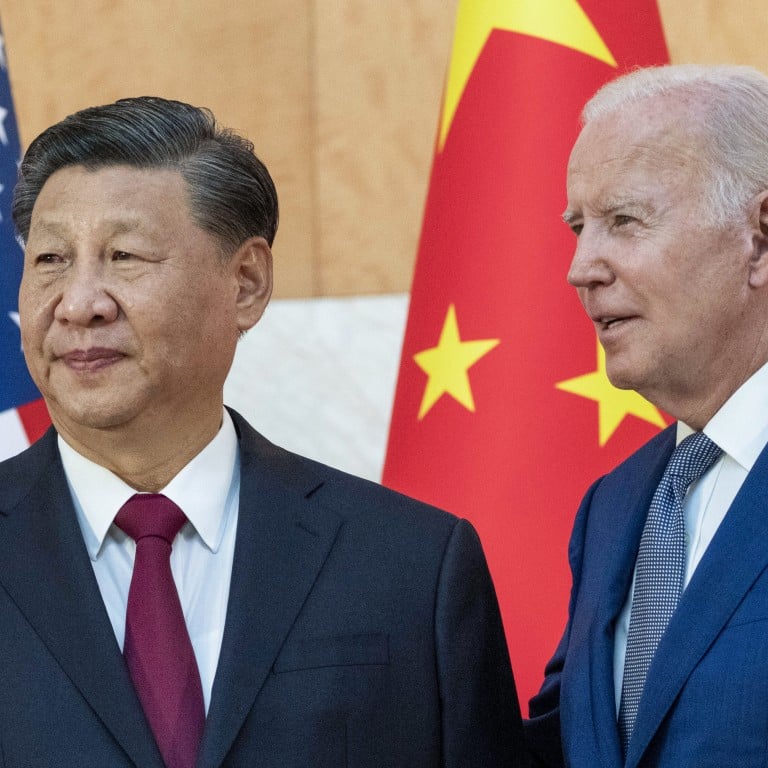

Using theory to guide US-China relations could be a recipe for disaster

- If policymakers in Washington and Beijing are overreliant on theory, and if their theories are predicated on seeing the other system as inherently evil, then the result could be war in East Asia

At the end of the semester, for me – a typical worn-out university professor – a measure of peace and tranquillity against the raging insanities of our time can be found in a little quiet time in my library. It’s almost a ritual now: holding a sort of seance with my books, huddling with these silent but highly informative old pals, maybe opening marked pages, reading aloud a little, but always underneath weighing which ones to put into the next China course I will teach.

A theory-based approach offers up the alluring notion that one or another theoretical system of ideas has the ability to scope out the current reality based on well-chosen interlocking principles, perceived laws or even mathematical formulas. And, once a given theory is in the air, it can shape how we perceive the world.

I worry I have been late to understand the evil that some theories can do. Instead of illuminating, they can blind. So, on the visit to my library the other day, I reached right for the top shelf and Richard Bookstaber’s acclaimed 2017 book The End of Theory. This is the kind of literary resident your library must have if you are, like me, a theory-sceptic.

His honest, minimalist message is that whenever “there is a high degree of complexity’, the best you can do is “figure it out as you go along”, adding that the probability of an economic theory proving definitive in a current crisis, or predictive of a future one, is inherently low.

Some people find this hard to believe. Policymakers who are wedded to theory will have none of this, of course, and there are armies of them in Washington, well armed with foundation and government grants, as there presumably are in Beijing. Alas, the theory crowd talks and thinks and even socialises in its own world. That world is theoretical.

Through continuous usage, the bikes become more than cheap transit; slowly but remorselessly, these simple machines grind away at the souls of their riders and begin to cohabit them. The good people become so psychologically dependent on these common conveyances that humans and machines start to identify as one. The novelist even has the main character get turned on by a “female” bicycle offering an exceptional saddle.

The situation is no laughing matter, but a cautionary tale. A police officer in the novel warns that these machine-persons are “a phenomenon of great charm and intensity and a very dangerous article”. They meld so smoothly into machine-age mechanical personages that you might miss the transformation – until you talk to them and with a jolt realise you are engaging with a half human, half machine and your former self is but half the conversation.

Yes, they come to share a single nature and, over time, become but half human, or rather, bicycle-humans. Despite the author’s artistry, don’t worry about them, they are make-believe. I only wonder about today’s theory-people.

That, perhaps as much as anything, might well trigger the outbreak of war in East Asia. Yes, they come to share a common nature and, over time, become bicycle-persons, no longer pure human beings. No disrespect intended: some of our theory-people are among our best and brightest, both in the US and China, but they in effect think more or less the same way. More and more, they let machines do crucial thinking for them.

Nuclear war is no laughing matter, but there is at least one arguably funny thing about this whole potential nightmare – that a mathematically computational possibility where one side could survive is conceivable. Perhaps such a morally questionable calculation should be laid at the feet of theory-people.

Tom Plate, Pacific Century Institute’s vice-president, is LMU’s Distinguished Scholar of Asian and Pacific Affairs in Los Angeles; prior to that he taught at UCLA. A Phi Beta Kappa member (Amherst College), he holds a masters in public affairs from Princeton. He is the author of the four-book “Giants of Asia” series