How chasing the sugar rush of monetary infusions gave us high inflation

- The world’s top leaders are responsible for this biggest misstep in our recent economic history

- The authorities blame rising food and oil prices or war – when the real cause is poor monetary and fiscal policymaking

These are embarrassing admissions by our economic leaders to the blindingly obvious.

This was done to resist the onset of recession, but slowdowns are part of a successful economic system, which eventually runs ahead of itself and then needs time to catch up, unclog, reset and renew. Economies are living and dynamic, they do not stay static and cannot be managed as if they do – an assumption that consigned the Soviet Union to history.

Indeed, today’s megalithic technology companies demonstrate that a disorganised and messy economy provides opportunities for renewal – as many emerged from a garage or a college dorm.

There has been no expression of regret or shame from experts who admit to having wrongly forecast inflation levels. Even teenage economic scribblers know that inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods”. It is often joked that economists make policy by looking in the rear-view mirror, but the targeting of inflation levels rather than worrying about money supply, was an example of putting the cart before the horse.

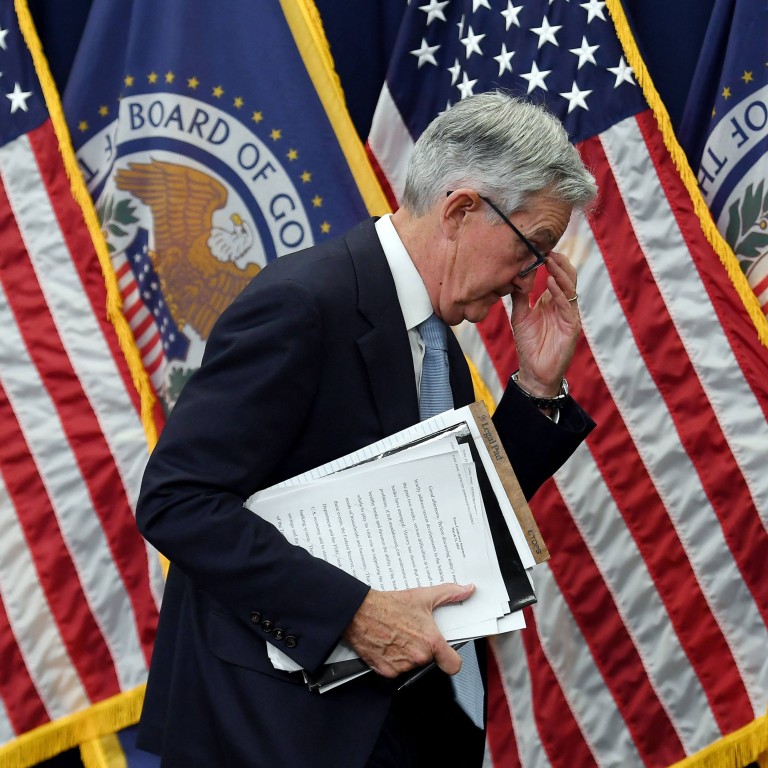

Schoolboy errors by these grizzled central bankers resulted from oversheltered groupthink, mutual self-satisfaction, political pressure or an emphasis of hope over reality. They convinced themselves, despite their experience, that printing money was not going to lead to a significant increase in prices. Their forecasters failed to realise that modelling economies on periods without shocks fails to pick up extreme shocks that periodically emerge.

Inflation as a concept is well understood by economists. There is no shortage of nomenclature, such as stagflation and hyperinflation or galloping, walking, headline and creeping inflation, or deflation, reflation, disinflation, falling inflation or built-in inflation. The latest buzzword is “greedflation” – where companies take advantage of the inflation narrative to put up prices and fatten profits.

Government-derived inflation rates are used to index a wide range of metrics, from wage rises and gross domestic product measurements to capital gains tax calculations. It is oh-so tempting to be economical with the truth. Inflation indices vary – from retail price indices to consumer price indices, from definitions such as factory gate and core, to fringe and with or without oil, housing or food. Such indices can and are manipulated by adding or dropping various components and promoting them as “headline”.

This can only go on for so long. The general population doesn’t care if the official inflation rate is 2.5 per cent if their lifestyle is inhibited by having to spend 20 per cent more on food.

Inflation supports the skilled and the already rich with rising wages, higher nominal profits and better investment returns. Companies save costs by getting rid of labour through mechanisation, adding stress to already pressurised government budgets. Policymakers remove moral hazard by subsidising inflated costs.

The only person in authority to come clean is British finance minister Jeremy Hunt, who said last week that he would be “comfortable” if further interest rate rises precipitated a recession, because “inflation is a source of instability”. Hunt showed great honesty, despite it being politically unhelpful. Across London, the fact that the Bank of England, well endowed with economics PhDs, still has “very big lessons to learn” about inflation indicates that the future of economic mismanagement is secure.

Richard Harris is chief executive of Port Shelter Investment and is a veteran investment manager, banker, writer and broadcaster, and financial expert witness