Southeast Asia’s businesses can embrace social responsibility now – or learn the hard way

- European laws such as carbon taxes and on supply chain due diligence are set to disrupt how business is conducted in Asia

- Importantly, research shows customers, investors and capital markets reward companies that materially improve the world

The case is clear – we must fix the pressing issues of pollution and social inequality that threaten our world. But who’s best positioned to make a positive and lasting social impact?

Traditionally, the role of implementing change has fallen to governments and charities. But these issues are far too complex and multifaceted for just those two stakeholder groups to address. There is a third player that can, and must, fill in the gap.

That outlines the stick that companies need to worry about. But what about the carrot?

There is also measurable impact – for consumer goods companies, the top decile of ESG performers attain stock market valuations that are 11 per cent higher, command price premiums that boost their gross margins by 4.8 per cent higher, and access one of the fastest-growing segments of the market.

Companies with material ESG programmes are also able to better attract and retain talent. Nearly two-thirds of millennials say they will not work for companies that are not socially responsible. Forward-thinking companies are evolving from regulatory compliance and charity, to creating real business value. It is a shift in corporate mindset from compliance to contribution.

When it comes to making a real impact, I believe, if done right, the private sector has a huge potential to improve the world. Aligning business goals to create social impact will give rise to socially transformative businesses that will be rewarded by customers, employees and investors. The key, however, is defining goals that are core to a company’s basic business with measurable achievements.

Plenty of CEOs tout their commitment to making a social impact. But too often, that amounts to little more than an annual corporate beach clean-up, a visit to a hospital or charitable donations. Such actions may be well-meaning but do not really amount to much. Instead, companies need to make it a core part of their business, and not just window dressing.

‘There is no escape’ from EU ESG disclosures, says global trade body head

One example is Ola. The Indian ride-hailing giant has built an electric scooter factory in Tamil Nadu that its CEO Bhavish Aggarwal has pledged to staff entirely with women.

Ola’s Futurefactory will be the world’s biggest two-wheeler factory when it hits its annual output of 10 million units, with one out of every seven two-wheelers in the world coming from the women-only plant. This is a great example of how a company can create real business value by incorporating social impact as a core part of the business, instead of as an afterthought.

In the food and drink sector, Starbucks is a great example of a socially transformative business, with social goals built right into their supply chain: 99 per cent of the global coffee chain’s coffee is ethically sourced – and given its huge demand, this can alter the entire industry’s profile.

More companies across industries in this region should take a page from Ola, Patagonia and Starbucks.

There are three ways to move forward – our analysis shows the most effective plans fall into three broad categories: an inclusive supply chain, an inclusive organisation, and inclusive products and services. Ultimately, every company must figure out its path. Done right, it will be rewarded by customers, employees, and shareholders.

It is no longer enough to follow the clichés of corporate social responsibility. Southeast Asia’s companies must be socially transformative, changing their operations from the core, from their suppliers to who they employ and promote, and who they ultimately service.

This is not a nice-to-have, but a must-have. Taking the right action will deliver true return on investment for companies, generate value across operations and drive positive impact for all.

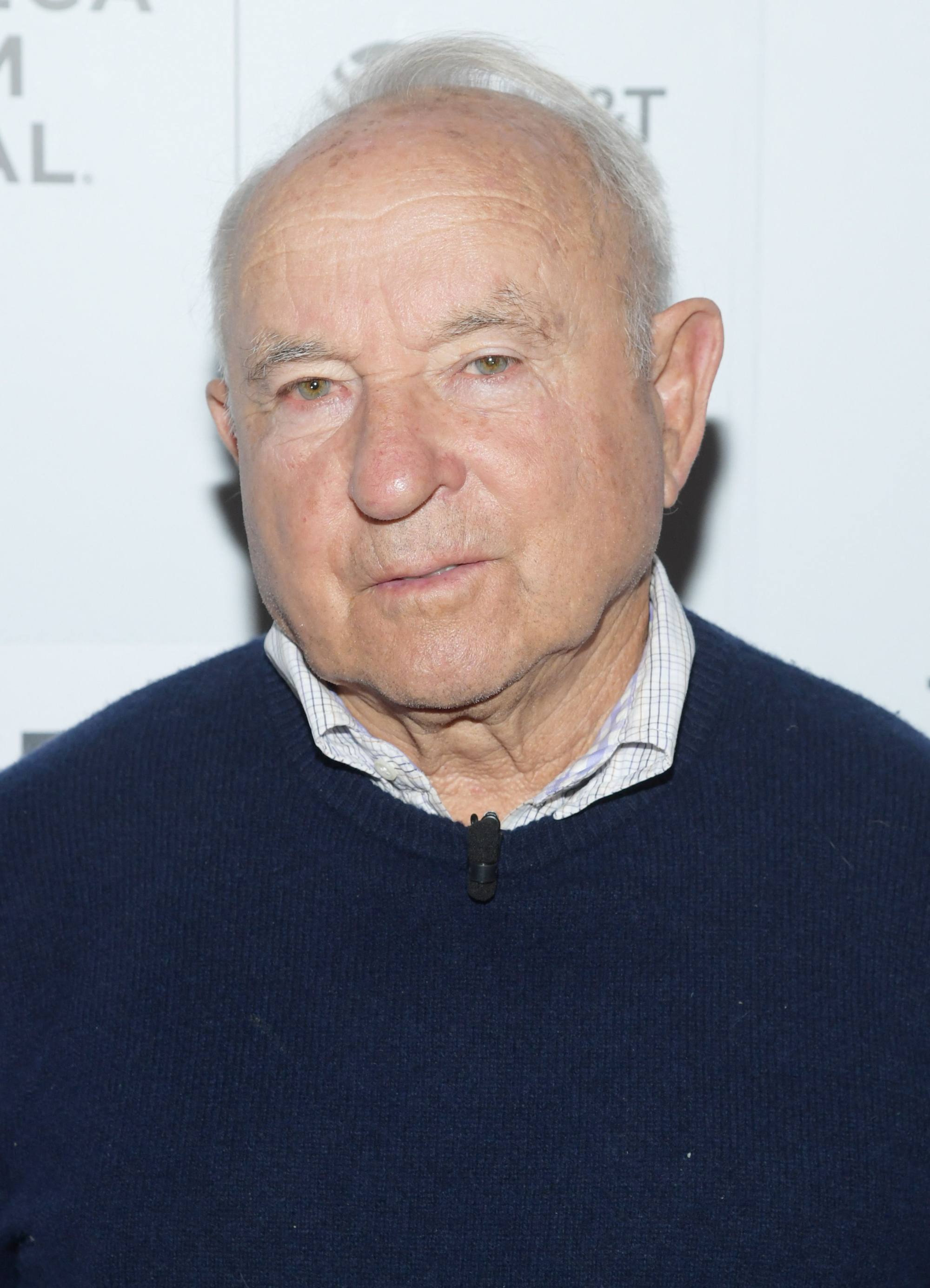

Vincent Chin is the vice-chair of Boston Consulting Group’s Public Sector practice globally and also leads the firm’s Social Impact practice in Asia-Pacific