What the South China Sea code of conduct talks should focus on instead of dispute resolution

- Better to let states resolve things bilaterally, given the complexity of the disputes and Asean’s traditional approach

- Instead, the code of conduct should bind China and Asean into good behaviours: respecting the status quo and refraining from military activity

A successful code of conduct would legally bind each party, halting China’s aggressive military posture against Asean members’ economic activity in the South China Sea, while regional states refrain from inviting or supporting US military intervention. It would ensure water disputes do not hinder economic development and maritime cooperation between China and Asean.

But the code of conduct should not govern dispute resolution. This is despite criticism that China prefers to resolve its disputes bilaterally and separately from code of conduct discussions because it would grant it greater leverage. Or that, unless Asean can establish a consensus in resolving maritime disputes with China, Beijing will be able to continue to offer economic benefits in exchange for shelving the disputes.

Indeed, China employs a “dual track” approach in the South China Sea: aiming to negotiate directly with claimant states while working with Asean to maintain peace and stability.

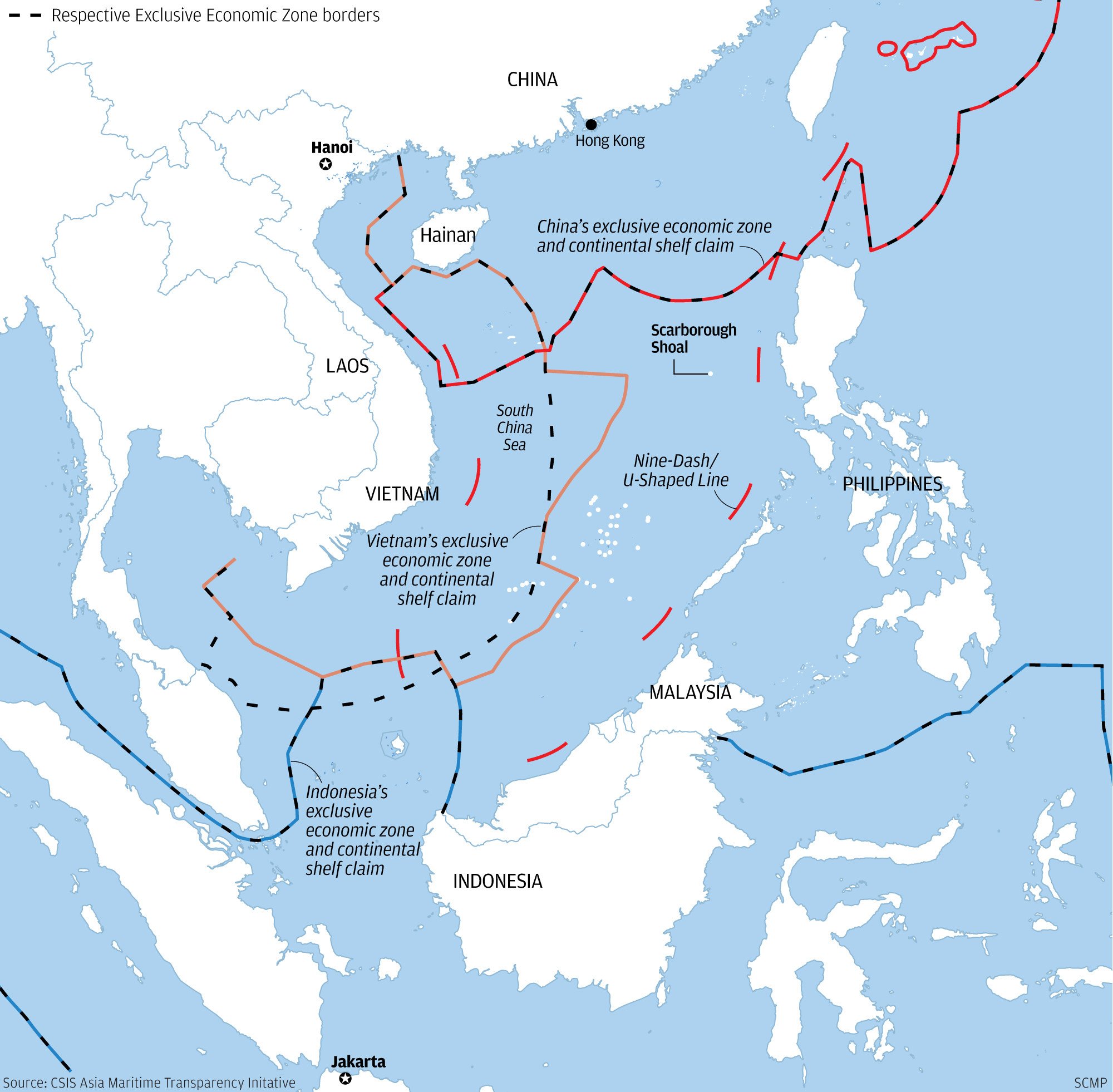

There are two key reasons the bilateral resolution of disputes is important. Firstly, the complexity of the disputes makes collective negotiations with China challenging.

Each country has its rationale for its claims. Moreover, some Southeast Asian countries have disputes with each other over areas also claimed by China, further complicating the resolution process.

Critics point out that many Asean members are China’s close economic partners, some have no disputes with China, and there are conflicting maritime boundaries among members. This lack of consensus hinders a collective approach.

That is true. But that premise also lends stronger support to pursuing the bilateral resolution of disputes. Given Asean’s inability to reach a consensus on regional disputes, discussing the matter within the bloc is futile.

Instead, Asean provides a framework to manage and address common challenges. In essence, regional countries show commitment to Asean by upholding its principles and pursuing the common goals of regional peace and stability. Other countries, in interacting with Asean, are also expected to consider the bloc’s principles. Asean values efforts by regional states to prevent, manage and ultimately resolve such issues.

To prevent the South China Sea disputes from escalating into conflict, one crucial step is to establish a legally binding code of conduct that explicitly addresses two key behaviours.

On Cuba or South China Sea, why has Beijing failed to rally support against US?

Secondly, the parties should abstain from military activity within disputed areas. China must be legally restricted from using military vessels to intimidate when other regional countries are carrying out economic activities in their exclusive economic zones or territorial seas. Likewise, Asean members should be prohibited from conducting military exercises, especially with external powers, or permitting their military vessels and aircraft to navigate in disputed areas.

Should any party breach these commitments, the opposing party would be authorised to pursue actions that align with its national interests. For instance, if China threatens the fishing and energy exploration of Asean members, they would be permitted to conduct military activities alongside the US and other nations within the disputed regions. They could also seek international intervention to hold China accountable. Conversely, if any Asean member violates the commitments, China would have the licence to respond militarily.

A binding code of conduct with these principles would pave the way for countries to peacefully pursue maritime cooperation, including joint economic development and fishing and energy exploration, in the South China Sea.

Riaz Khokhar is a research analyst on geopolitics and security of the Indo-Pacific region and a former Asia studies visiting fellow at East-West Center in Washington