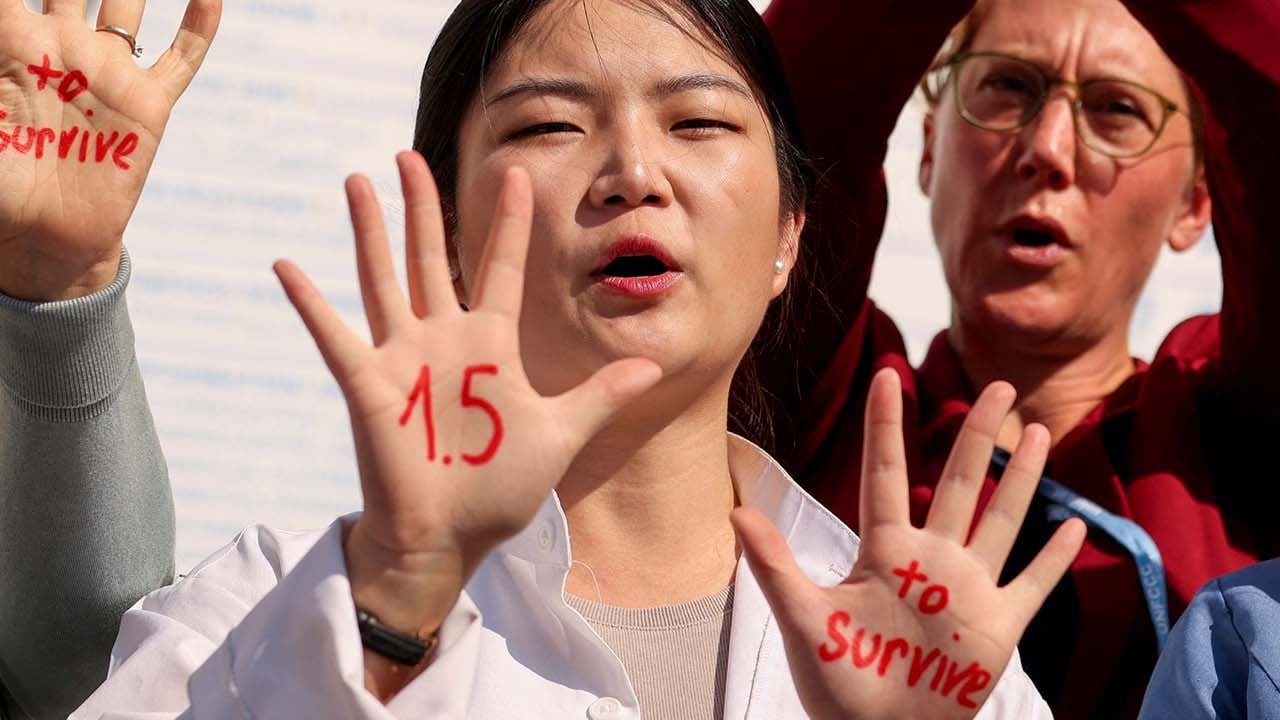

COP28: Companies’ embrace of carbon credits puts to shame countries’ climate backsliding

- Governments are not on track to meet the target of limiting global warming, and some, particularly in the Global North, are retreating from measures to combat climate change

- However, more firms are offsetting emissions with carbon credits – and research shows such companies decarbonise faster

But instead of inspiring extra effort, the risk is that governments will attempt to backslide on their carbon commitments, judging that politically, a weak promise kept is better than a bold promise broken. This risk is underlined by wavering support for climate policies in some rich countries.

The consequences of a global backslide on carbon commitment on the safety of everyone on Earth are considerable. Worryingly, it may usher in a period of conflict between wealthy Global North nations and developing Global South states.

These projects could help countries without sufficient government funding to transition away from fossil fuel-powered grids to renewable energy, to protect and restore forests, and reduce waste going into landfill. When you consider that investments in these three solutions could eradicate nearly three-quarters of harmful emissions, it seems a case of cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face.

The stasis is driving a wedge between the Global North and South when all nations need to work together.

While the situation is dire, there is hope, albeit from an unlikely direction: the private sector.

This market allows businesses to offset any carbon emissions they cannot eradicate from their operations. In effect, it means businesses pay compensation to the planet for the carbon they emit.

This compensation, in the form of carbon credits, is directed to projects – usually in developing countries – that are proven to avoid or remove carbon emissions. These credits are bought and retired by companies, at which time they are called a carbon offset.

Fight climate change by funding concrete projects, not pious hopes

Despite driving finance to where it can have the biggest effect on mitigating climate change the fastest, the voluntary carbon market has experienced headwinds in the past 12 months. Critics in the European media have sought to deter the use of carbon offsetting, claiming the voluntary carbon market slows direct decarbonisation.

The reality is that we cannot address climate change without a massive increase in corporate emissions offsetting. This explains the growth of carbon offsetting as a climate solution.

Analysis by market research firm Allied Offsets shows an over 50 per cent increase in companies retiring credits this year compared to 2022. Of those, nearly two-thirds (63 per cent) had retired more credits in the first nine months of the year compared to the same period last year.

At least eight of the world’s 10 most valuable brands, including Amazon, Alphabet (Google), Apple and ByteDance (TikTok), use carbon credits – they know they can protect brand value by taking climate action.

Carbon credits amount to more than greenwashing

Not ones to fall behind, South Korea and Japan are also putting in place carbon trading systems.

To stay on track for the 1.5 degree target, carbon credit projects need an estimated US$90 billion more in finance by 2030; if we are to keep the global temperature increase within safe levels, many more private businesses will need to take the plunge and offset their emissions.

Relying solely on governments in the rich countries of Europe and North America – who have shown willingness to stall and backslide at the first opportunity – is a path to climate purgatory.

Rich Gilmore is CEO of Carbon Growth Partners