In Hong Kong, the alarm bells are ringing for children’s mental health

- Child abuse is on the rise, alongside mental disorders and suicides among youngsters, with too many still not getting the help and treatment they need

It’s not hard to identify youngsters needing help; the telltale signs are obvious. If a child or adolescent is depressed for long periods, exhibits confused thinking, worries excessively about things, experiences mood swings, withdraws from friends and activities, or exhibits significant tiredness and low energy, the alarm bells should be ringing.

The researchers, between 2019 and 2023, interviewed 6,082 children and adolescents, as well as their parents, and found that one in 10 children and adolescents suffered from significant sleeping problems. The most common condition was ADHD, which afflicted 10.2 per cent.

The study also found that almost 50 per cent of carers, despite observing mental health problems in their children, were unwilling to seek professional help for them. This was mind-boggling, and points to a system in need of overhauling.

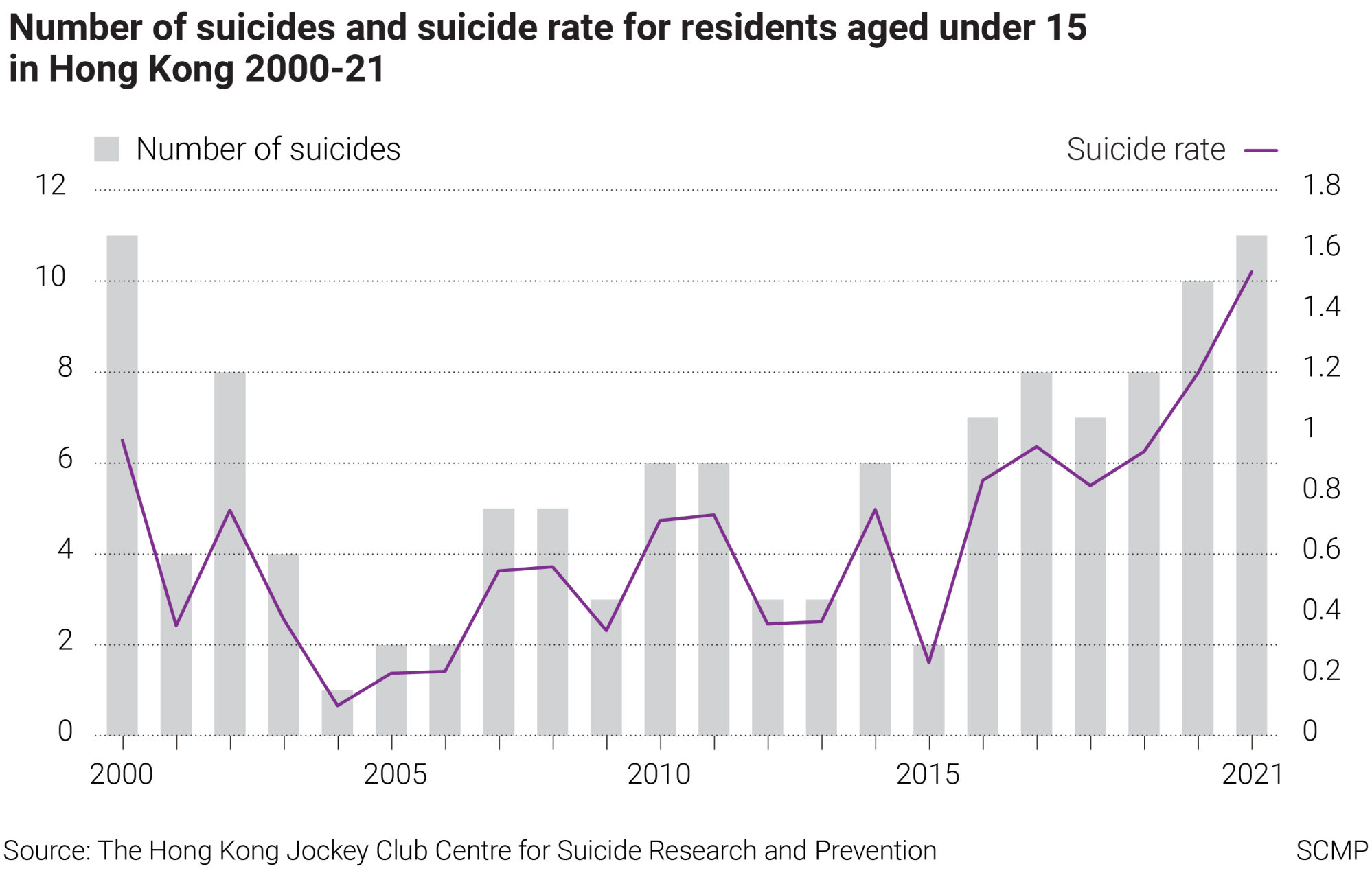

Moreover, the Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention at the University of Hong Kong announced last month that 37 students had taken their own lives since January, with 269 students known to have attempted suicide this year. It noted that school-related matters, family issues and mental health problems were the main contributory factors.

What was particularly disturbing was the disclosure that, out of the 306 students who attempted or died by suicide, over 55 per cent had reported their mental problems but fewer than 40 per cent had received treatment from welfare professionals.

Regrettably, the community’s capacity to respond to this troubling situation is questionable. The founder of HKU’s Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention, Paul Yip Siu-fai, said last month it was “impossible to deal with all the children and adolescents with mental disorders with our medical system as we do not have the manpower” – which comes as a surprise.

After all, since 2019-2020, the Social Welfare Department has set aside an annual provision of around HK$56 million (US$7.2 million) for its integrated community mental health centres, and this should have helped. The sum was to enable the centres to extend their service targets to secondary school students with mental health needs, and strengthening support for them, their parents and their carers.

Although the centres provide such things as public education on mental health, clinical psychiatric services and community outreach, they depend on referrals from doctors, social worker and others, and the system is not working as intended.

Last month, five NGOs, including Caritas Hong Kong, exhorted schools to provide more mental health support for students, and urged parents and the public to be on the alert for “warning signs”.

Hong Kong must not fail pupils in need of mental health support

On November 22, Secretary for Education Choi Yuk-lin told the Legislative Council that the government would be establishing “a three-tier school-based emergency mechanism”, which sounds promising.

It would involve the early identification of adolescents with mental health needs, an “off-campus support” network, and the direct referral by school principals of students with severe problems to Hospital Authority psychiatrists. The aim was the promotion of “students’ physical and mental well-being”; the proof of the pudding will now be in the eating.

Although fine words and good intentions have never been in short supply, they alone cannot suffice. With more enlightened attitudes and greater resolve, the case for the prioritisation of the mental wellness of children and adolescents is now overwhelming. In 2024, the authorities must implement clear strategies that will realistically promote the mental health of young people, whatever their age.

Grenville Cross SC is the patron of Against Child Abuse