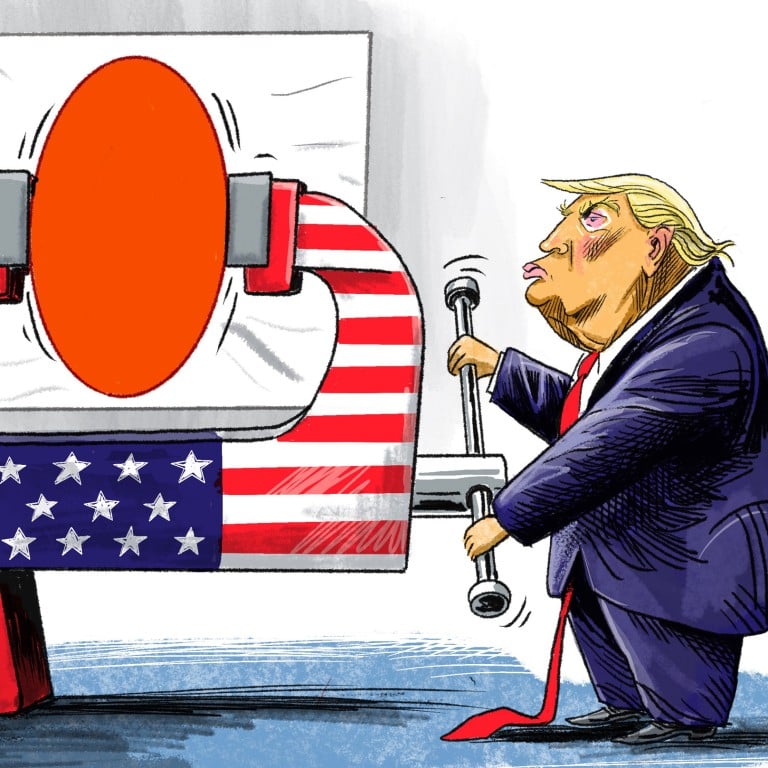

Stuck between China and the US, flailing Japan needs a grand new plan

- Faced with economic woes and geopolitical uncertainties that have left it increasingly squeezed between a resurgent China and an unpredictable ally in America, Japan needs a grand new strategy

“We will advance the fundamental reinforcement of Japan’s defence capabilities in tandem with reinforcing the Japan-US alliance and strengthening our security cooperation with other like-minded countries,” he added.

Japan’s decline is arguably more dramatic than in any other major nation in recent memory. In the 1990s, Japan’s gross domestic product represented 15 per cent of the global economy. Today, it stands at just over 4 per cent. In the same period, China’s share of global GDP has risen from 2 per cent to 18 per cent.

The picture is even more dramatic in East Asia. Between 1990 and 2014, Japan’s share of regional GDP collapsed from over 70 per cent to around 20 per cent, while its share of regional trade declined from over 45 per cent to barely 15 per cent. In contrast, China’s regional trade ballooned from under 10 per cent to more than 40 per cent, while its share of GDP rose from under 10 per cent to more than 50 per cent in the same period.

For Japan, the China challenge goes well beyond sheer numbers. In particular, senior Japanese officials are concerned about China’s rapid advancements in cutting-edge technologies, namely in artificial intelligence, quantum communications and renewable energy.

What if China declared a protectionist trade war on the US and the West?

In particular, China has the ability to restrict not only access to its massive consumer market, but also deny Japan access to its rare earths and critical minerals in the event of economic warfare. There are also growing concerns over contingencies, most notably over Taiwan.

Japan’s defence policy calculus, however, is largely shaped by its alliance with the US. And this is precisely why the Japanese strategic elite is deeply perturbed by the prospect of a second Trump administration, which could prove even more unpredictable and transactional than its first iteration.

Donald Trump as US president again would be the stuff of nightmares

But with its penchant for “America first” unilateralism, a second Trump administration is unlikely to employ a genuinely consultative and multilateral approach to its Asia strategy. This could, in turn, erode trust and undermine coordination among the US and its key allies, especially Japan.

As a result, Japan has found itself increasingly squeezed between a resurgent China and an unpredictable ally in America. It remains to be seen, however, whether a new era of geopolitical uncertainty will usher in an entirely new grand strategy for Japan, which has largely acted in America’s shadow since the end of WWII.

Richard Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author of Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China and the Struggle for Western Pacific, and the forthcoming Duterte’s Rise