Hong Kong show of underground 1990s Chinese art offers different perspective on era

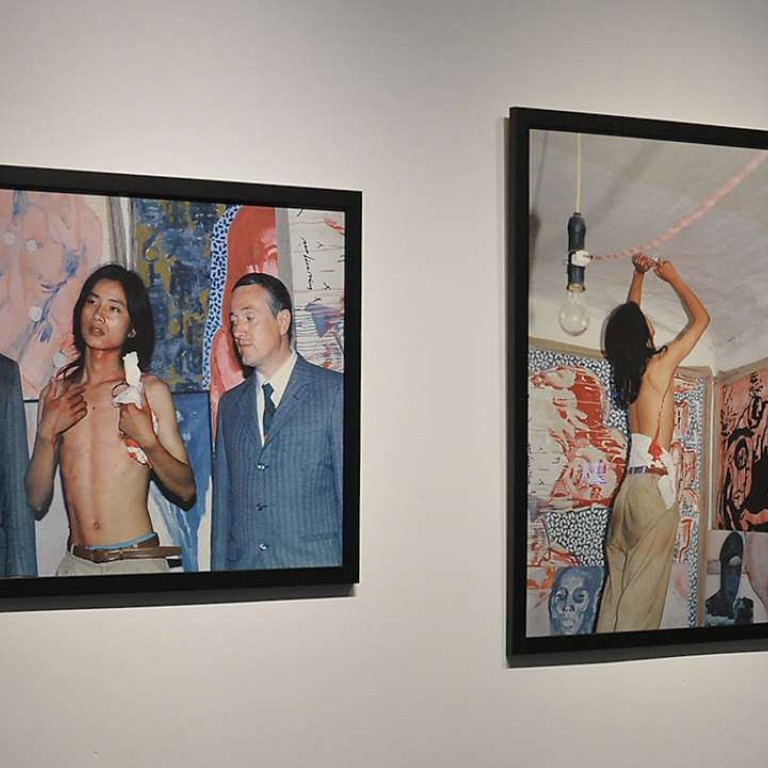

Curators at Para Site avoid works by artists usually picked to represent 1990s Chinese art, opting instead for works that, while sometimes political, focus largely on the decade’s get-rich-quick mood

A new show at Hong Kong’s Para Site exhibition space is a reminder that mainstream narratives have a tendency to obscure what artists do during periods of great political change.

Those narratives affect how we see art history. After the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, it was assumed that the restrictive environment forced artists to either go into exile or express their frustrations by painting in the style of political pop or cynical realism, styles which would meet with internationally success and make them very wealthy indeed.

As the two China-born curators of the Para Site exhibition explain, this show, “That Has Been and May Be Again”, deliberately avoids artists who have come to represent 1990s Chinese art. Instead, Leo Chen and Wu Mo have chosen underground artists who were active at the time.

“The art world was highly fractured. This exhibition is not a retrospective. We just want to tell people that Chinese contemporary art has many different layers,” says Chen.

The title – taken from Yu Dafu’s story, Sinking – refers to the many invasions, civil wars and power struggles that have plagued modern Chinese history. Artists react to external factors, of course, but each in their own way.

“We want to respect each artist’s individual voice, whether they choose to make active or passive comments. There’s no right or wrong about it,” Wu says.

The year 1989 was significant for two things: the violent crackdown on youthful, democratic aspirations, and the scaling up of China’s market economic reforms.

Zheng Bo made the only exhibit with a direct reference to June 4. Using weed, he has created a living tapestry of Liang Xiaoyan’s face. Liang was a young university lecturer who supported the protesters in Tiananmen Square, but also spoke out against protest leaders for putting the students in danger.

Since 1989, she has become an activist focusing on environmental issues and the lack of education in rural villages. For Zheng, Liang is an example of someone who does not always act as others do but who, through her own quiet persistence, has made more of an impact in China than the heroes of 1989 who were venerated by the Western press.

In 1967, as anti-colonial riots spilled onto Hong Kong’s streets, Beijing and London engaged in a war of music through public loudspeakers. The Bank of China Building would blast out Cultural Revolution songs while the British side would play songs by the Beatles, an absurd scenario captured by Leung’s installation.

A toy plane made from a 1967 Life magazine cover twirls around an axis to the rhythms of Long Live Chairman Mao and Yesterday, a playful commentary on propaganda and cultural identities. “He’s not from China but we decided to include his work because it is such a wonderful fit with our themes,” Chen says.

“That has been and may be again”, Para Site, 22/F, Wing Wah Industrial Building, 677 King’s Road, Quarry Bay. Wed to Sun 12pm-7pm, until August 21