Akram Khan mines Indian spiritual soap in Hong Kong-bound Until the Lions

Dancer and choreographer made his name in Peter Brook’s adaptation of the Mahabharata, and returns to the Sanskrit epic for New Vision Arts Festival production about love, revenge and betrayal

Akram Khan is a busy man. In the four months leading up to his performance in Hong Kong in November, he had only one time slot available for this interview. And during our 20-minute talk, Khan managed to drive to work, park his car, walk into the English National Ballet in central London, where he is choreographing Giselle, and order breakfast from the canteen.

One of the many things Khan has been busy with is a show called Until the Lions, which premiered in January at the Roundhouse in London, and will make its Asian debut in Hong Kong as part of the biannual New Vision Arts Festival. This year’s edition will run from October 21 to November 20.

It is based on one story from the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata, about Princess Amba, who is abducted by her fiance’s enemy, Prince Bheeshma. Despite being released later, Amba is rejected by her family and by the King of Shalva. She has no one left, so she turns to the gods.

“The story is about love, betrayal and revenge,” says Khan.

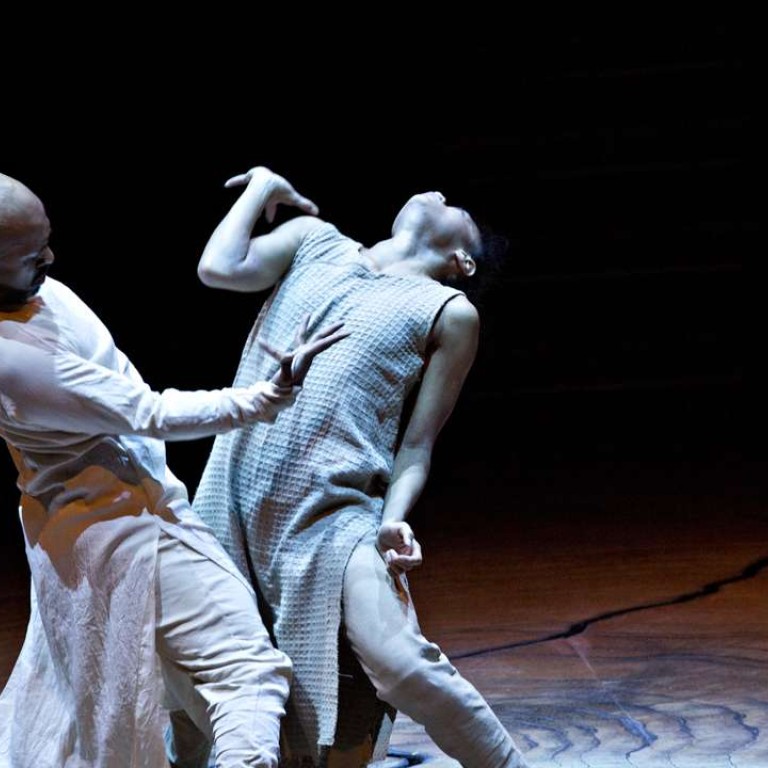

Not only is Khan directing and choreographing, he stars as Bheeshma. Taiwanese-born Chien Ching-ying is Amba, and Filipino-American dancer Christine Joy Ritter plays Shikhandi, the male version of Amba.

“Until the Lions was supposed to be my last solo and then I realised I had just made a solo a few years back and I was pretty bored and lonely up there on my own,” Khan says.

“I felt it wasn’t the right time and I wanted to work with Ching-ying and Christine – they are special dancers and I felt they had the capacity to embrace such a responsibility and take the space [on stage] with these huge characters and they did so eloquently and powerfully.”

It was inspired by a book of poet Karthika Nair, who has worked with Khan on several previous choreographies, and it reflects their shared interest in how often women’s stories are lost in these great epic histories – and yet how often they have, within them, the nubs of greater human truths.

It is, by all accounts, very beautiful.

It could, in a way, be seen as inevitable that Khan should do something about the Mahabharata because, of all the great spiritual classics of the Indian subcontinent, this was the one that changed his life. At the age of 13, having trained in Kathak (a form of Indian classical dance), Khan was recruited by the avant-garde theatre director Peter Brook to be the youngest performer in his epic version of the Mahabharata.

“I was very close to the Mahabharata because it was a big chunk of my childhood acting in it,” Khan says. “But at the same time Peter Brook had a huge influence on me with his way of storytelling. The simplicity and pedestrianness in the manner he tells stories always inspired me.”

In Brook’s version he stripped everything back to the bare bones, he adds. “We Indians have a tendency to decorate everything but he reduced the story back to the absolute essence of what it is about, particularly about human relationships.”

The Mahabharata, Khan says, is “a spiritual story in a soap form. Like episodes on TV … the difference is that it has gods and humans. It’s there to teach us about ourselves and to reflect on ourselves.

“All great mythologies have a wide spectrum of human emotions and narratives. There’s good and bad and there’s what’s in between. There’s a betrayal, there’s love, there’s anger, there’s cheating. It reflects so much of civilisation really.”

All great mythologies have a wide spectrum of human emotions and narratives. There’s good and bad and there’s what’s in between.

The story of Giselle is not unlike the Amba tragedy in some of its elements, but with very different decisions and resolutions. They are both epic stories of female characters who are brought back to life in order to deal with the cosmic motifs of love, betrayal, and – in the case of Giselle, if not of Amba – forgiveness.

“It’s a huge challenge,” Khan says, as he walks through the corridors of the English National Ballet, greeting his fellow collaborators. “It’s quite frightening because with Amba and Shikhandi, it’s not a choreography that people have done so much. But with Giselle it’s been done so many times and in so many versions, and it’s quite epic, with more than 40 dancers and more than 60 musicians.

Khan began the creative process of Giselle by looking carefully at the original version, and the original story, before simplifying it.

“I wanted to relate to who is Giselle in this time and space, and strip it back from the decoration [of the 19th and 20th century versions] to the essence of it and to this one woman’s journey.”

Working with classically trained ballet dancers involves a huge adaptation for Khan’s own process. “It’s an extremely different body and a different technique and that’s what is exciting to me. I’m exploring new ways ... I’m learning a lot,” he says.

And then he is off, to begin a new day of doing what he likes best – exploring huge, cosmic, universal themes through the sometimes small, sometimes frail and always very human form of physical dance movement.

Until the Lions, Akram Khan Company, November 19, 8pm and November 20, 3pm. Hong Kong Cultural Centre Grand Theatre, HK$140 to HK$480. Inquiries: 2370 1044