From Candy Crush to Minecraft: the rise and rise of Sweden’s video game industry

Swedish video game makers are being courted by US giants such as Microsoft and EA Games, who pay massive sums for their hugely successful titles

Microsoft raised a few eyebrows in 2014 with the announcement it was spending a hefty US$2.5 billion to buy Mojang, the Swedish developer of world-building game Minecraft.

The reaction among the fast-growing video-game industry in Stockholm was a little different.

“For us, it was like, ‘Microsoft got a pretty sweet deal’,” says Susana Meza Graham, an executive with Swedish video-game maker Paradox.

Minecraft, by the time Microsoft came calling, was a global phenomenon. It instantly gave Microsoft a hugely popular brand with kids and gamers of all ages, as well as the US$100 million or so in profit that Mojang was then pulling in annually.

Bringing Mojang and its 35 employees under Microsoft’s umbrella also put the American company at the centre of a vibrant video-gaming cluster.

Sweden’s video-game boom in the last half decade is one of the biggest success stories in the industry, fueled by a talented and creative workforce and the fruits of years of government support for education and technology.

And an industry trade group estimates that one in every 10 people in the world has played a game developed in Sweden, from casual titles (Candy Crush) to the high-end (Battlefield) and whimsical (Goat Simulator).

Recently, many have plugged into Minecraft, an open-ended game that lets players pilot blocky characters and build elaborate universes. The game has sold more than 122 million copies, the second-biggest all-time seller behind Tetris.

Stockholm, Sweden’s largest city and home to 930,000 people, is spread across an archipelago of 14 islands and coastline where Lake Malaren meets the Baltic Sea.

Just to the south sits Sodermalm, an island primarily used for farmland until its bogs and lakes were drained and working-class housing was built in the 19th century. Today, it is Stockholm’s cultural capital, and the heart of its gaming scene.

One recent Friday, Meza Graham and most of Paradox’s 220 employees gathered on the sixth floor of their Sodermalm headquarters to toast – prosecco in hand – the simultaneous release of two updates to their games.

Avalanche, another development studio, occupies two floors of the same building. Dice, the biggest employer in Sweden’s gaming industry, is headquartered across the street.

“This would have to be the most populated game-development area in the world,” says Jacob Kroon, a spokesman with the Swedish Games Industry trade group.

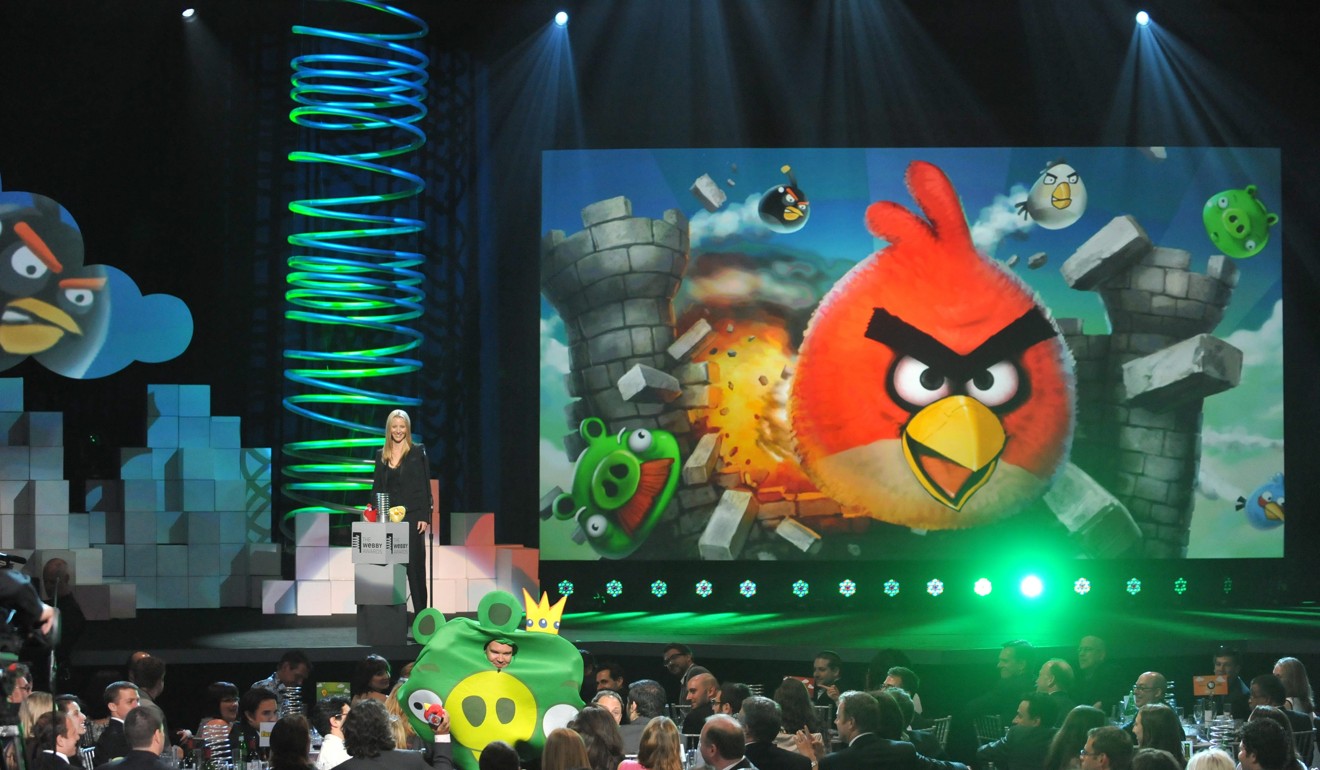

A few blocks away down a street of utilitarian-looking apartment buildings and brick-walled former factories converted into offices is a subsidiary of Rovio, the Finnish-headquartered Angry Birds builder. And around the corner from there, on the first floor of an old tobacco factory, is Mojang.

The company was founded in 2009 by Markus “Notch” Persson, who built Minecraft in his spare time.

Early on, he spurned a job offer from game publisher Valve, which wanted him to bring his game idea to the Seattle-area company.

After the sale to Microsoft closed, Persson and Mojang’s two other founders left the company.

Microsoft’s purchase of one of Sweden’s crown jewels of video gaming sparked the concerns that typically come when a big company acquires a smaller one.

New oversight and an infusion of foreign corporate culture can end what made the acquired company successful in the first place, particularly in the creative and personality-driven video-gaming industry.

There were “a lot of worries” among employees at Mojang, said Jonas Martensson, who joined the company the year before the deal and would stay on afterward as chief executive. “What would Microsoft do? Who would we work with?”

Microsoft hasn’t really shown yet what they want to do

But executives and developers in Stockholm say they haven’t seen much change in direction from Mojang in the 2½ years Microsoft has owned the studio, which now employs more than 50 people here.

From outward appearances at Mojang today, there’s little to suggest the company even belongs to Microsoft.

Much of the change has been in the Seattle area, where Microsoft has set up a studio to pilot some editions of Minecraft, and used the game prominently in marketing materials, including for the HoloLens, Xbox and the company’s education initiatives.

“Microsoft hasn’t really shown yet what they want to do,” said Patric Palm, chief executive of Hansoft, a Sweden-based game and software development toolmaker. “And since they paid such a hefty price, they obviously have a bigger game in mind here.”

Some Swedish game studios have flourished under new management.

Instead of withering, Dice has thrived. It employs more than 550 people in Sweden, including the team behind the hit Battlefield 1. Dice’s chief executive at the time of the sale, Patrick Soderlund, now runs EA’s worldwide network of studios.

Another Swedish gaming company, Massive, has kept producing hits in nearly a decade as a subsidiary of French gaming giant Ubisoft.

“If anything, [international acquisitions] have only been positive” for the local industry, said Oskar Burman, an industry veteran who has led Stockholm studios owned by EA and Rovio, among others.