Hong Kong-bound artist Sarah Morris, showing in Beijing, talks about films and the Olympics

American artist Sarah Morris muses on the restless spirit that inspired her films and paintings ahead of her show at White Cube in Hong Kong in May

Twenty years ago, the American artist Sarah Morris shot her first film, Midtown. There’s no narrative. She went out into the streets of that particular area of Manhattan for one day, and subdivided it into visual segments. Against the specific grid of the city, unintended patterns of colour (men in shirts) and texture (fountains) reoccur.

Ten years later, in 2008, she went to Beijing to make a film of that name during the Olympics. Beijing, too, is a city that was built on a specific grid. Again, other patterns (the Bird’s Nest stadium) and textures (ducks) emerge. Once more there’s no narrative, just insistent, electronic music by Morris’ then-husband, British artist and former Turner Prize nominee, Liam Gillick.

Wong Kar Wai photographer shares dystopian vision of Hong Kong youth in the age of smartphones

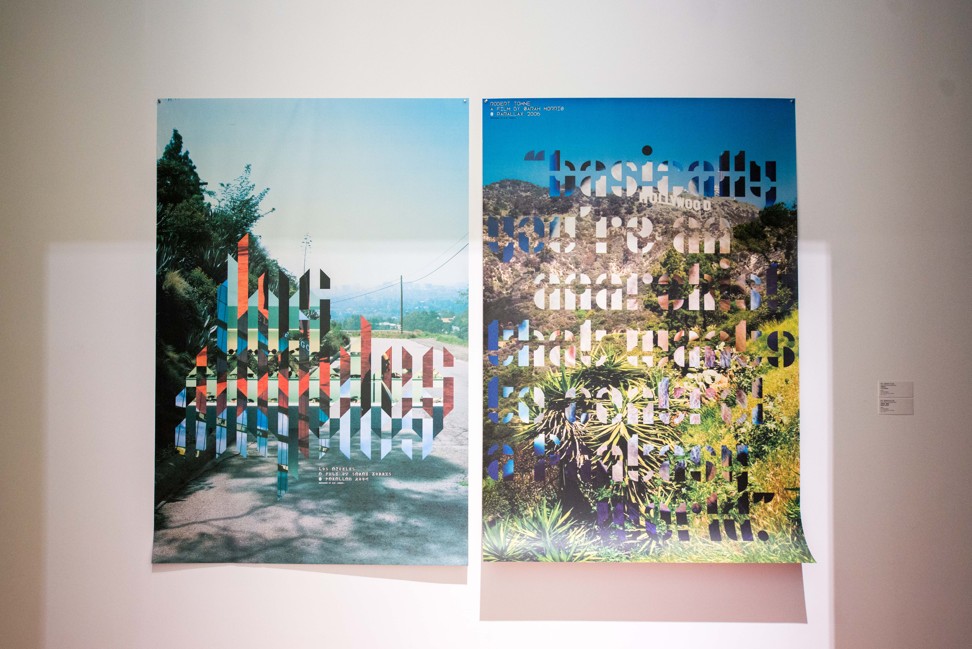

To mark both anniversaries, the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing is having a Morris exhibition. It’s the first time her entire output of 14 films are viewable in one place. Such fixity of location is unusual because Morris, who has shot in Los Angeles, Rio, Paris and Abu Dhabi, is a wanderer. The title of the show reflects the urge: “Odysseus Factor”.

“I love what [conceptual artist] Lawrence Weiner once told me – that artists are like expensive pieces of luggage,” she says in her New York studio in Long Island City.

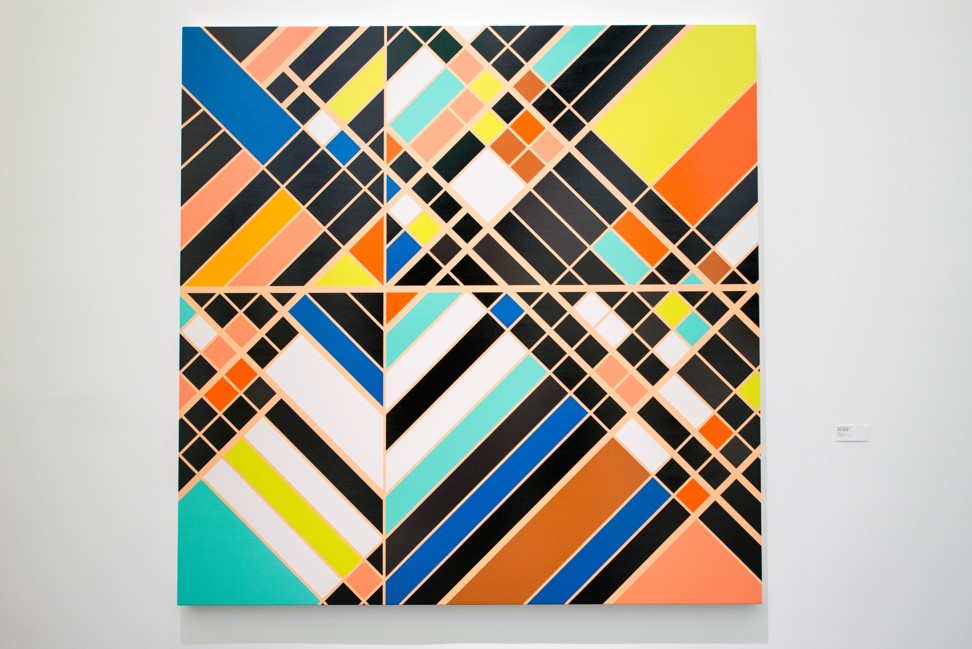

At 10,000 sq ft it’s the sort of space that can induce envy in a Hong Kong resident. Morris is also a painter of vivid geometric abstracts and the UCCA show includes what the press release refers to as some of her new “monumental” creations. On a February afternoon, she is working in her studio for a White Cube show that will open here in May. For Hong Kong, she concedes, “I want to have at least a few different elements of scale”.

Slender, dressed in black and passionately eloquent, she is like a living exclamation mark moving through the bright shapes of a kaleidoscope. Her company name, Parallax – taken from the 1974 classic conspiracy-thriller The Parallax View – refers to her desire to register how the appearance of the world shifts depending on where you’re looking at it.

“It’s not a causal, linear thing, like, I shoot a film, then I make the paintings,” she explains. “With the type of painting I do, there’s a set of coordinates, and you have to do layer after layer, it’s very slow. You can’t butt into the timing.”

Hong Kong domestic helper’s upcycled fashion collection combines empowerment and empathy

Filming, however, is all about time. Some of her exhibitions have included artworks of her shooting schedules, measured to the second: 10.06.15: McDonald’s/woman eating lunch, 10.06.45: McDonald’s/woman leaving, 10.07.07: McDonald’s/drinks/hand/manicure. Like the paintings, filming has its coordinates too, charting light and colour, but the results are speedier. She uses both to express the psychology of place.

The genesis of Midtown, nine minutes and 36 seconds of quintessential New York, began in London. Morris, 50, was born in England, to an English scientist father and an American mother. She grew up in the States, but has spent time in both places.

Distance lent, if not exactly enchantment, then an outsider’s focused eye. After seeing a 1996 White Cube show of her paintings in London, Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany, agreed to part fund a film to be shown in an exhibition it was planning called I Love New York. That became Midtown where Morris had a studio on 42nd Street. “It was loud, edgy and, in a solipsistic way, it was the middle of my universe. That is what I was starting to do – I place myself in a situation and I’m interested in capturing its momentum and adrenaline.”

As she moved into less familiar territory, the films became longer – Capital, in Washington, is 18 minutes 18 seconds, Los Angeles is 26 minutes 12 seconds and Beijing is 84 minutes 47 seconds. The progression from one to another appears to have been mapped out emotionally. While she was doing Los Angeles and dealing with the “monstrosity and corporations” of Hollywood, she decided she wanted to be in Beijing. “I was with Faye Dunaway and she wouldn’t allow me to film her without make-up or whatever, I was thinking, I’m so sick of this ego thing – I’m going to China to focus on the nation’s thinking, not the individual.”

Jeff Koons talks ‘plastic art’, selfies and Art Basel

In 2008, of course, Beijing was putting on its own make-up, ready for its close-up. “I wanted to be there not only for the spectacle but – and this was an important thing – to ignore the spectacle. I was politically taken to task by friends of mine, this question of whether you should be engaged with things that are problematic, contemptible, repulsive. I would always say as an artist, yes, you should be.”

By this, she doesn’t mean the Chinese government (“They weren’t involved, they were no problem whatsoever!”) but the International Olympic Committee who, for a fortnight that August had, as she puts it “sovereignty over the capital”. What would her friends say about their attitude now? “They’d laugh. It looks silly and pedantic not to engage with forms that are possibly bigger than ourselves.”

Along the way, she has learned “a certain way of approaching things”. She is a persuasive character, disinclined to hear the word “no” when there’s a possibility of “yes”. You see that bold tenacity in her art. “You’re working, of course, for yourself but also, in some ways, you become part of your work. You’re navigating something and you don’t know where it’s going to take you, and to me that is the pleasure.”

She hasn’t been back to Beijing since that summer a decade ago, and she is never been to Hong Kong. Trips to both places, as well as to Japan where she is involved in a museum project, will be part of what she is calling her “Asian spring”.

At the White Cube show in May, she’ll be showing her film on Abu Dhabi, commissioned by Nancy Spector, artistic director of the Guggenheim. That museum’s plans to open an outpost in the United Arab Emirates may have been much delayed but, for Morris, an artistic creation is still possible.

That viral Hong Kong miniatures artist, Joshua Smith, is coming at last to see city for real, and show new stuff in street art exhibition

“It relates on so many levels to where we’re at now in issues of energy, oil, landscapes,” she says of her film. These days, the Odysseus factor goes beyond mere human wanderings. “What the whole globalisation means is that art is moving around.”

Odysseus Factor is on at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art, Beijing until June 17;

Sarah Morris, White Cube (Hong Kong), May 24 to July 7