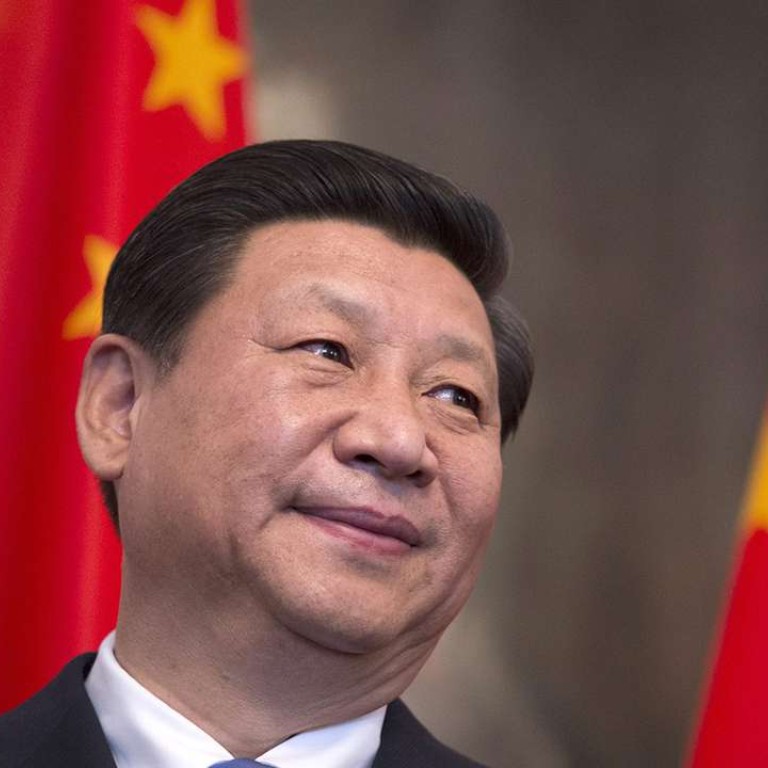

Review | Book review - CEO, China: The Rise of Xi Jinping by Kerry Brown – ‘peasant emperor’ in spotlight

China expert Kerry Brown traces the ascent of China’s president, from manure carrier to conduit of the country’s hopes in a book that’s too deferential and could have used more personal insights

CEO, China: The Rise of Xi Jinping

by Kerry Brown

I. B. Tauris

3 stars

In 1969, future Chinese president Xi Jinping was banished to the wilderness of Shaanxi province in northern China. As part of his seven-year schooling in rural life, the 15-year-old carried manure and built dams, learning two vital lessons.

“One was to let me understand what is realistic, what is the meaning of seeking truth from facts, and what the people actually are. The other was to strengthen my self-confidence. As the saying goes, a sword grows sharp when rubbed against a stone, and men grow stronger through hardship,” Xi is quoted as saying in this new account of how he became China’s chief executive.

According to China expert Kerry Brown, Xi’s stint in the wilderness was lucky. After all, Shaanxi had served as the Communist Party’s revolutionary base since 1935, when the Red Army ended its Long March retreat there.

Xi’s ties to the base would boost his image as a faithful party supporter. Starting out as a village official, he gained all-round experience at different government levels, before evolving into a “peasant emperor” untainted by revolutionary violence – or that is how his fans see him. CEO, China maps Xi’s grassroots climb to the top in March, 2013, when he succeeded the low-key Hu Jintao.

Since, through a Pope Francis-style corruption clean-up conveniently resulting in rivals’ imprisonment, Xi has bolstered his status. Armed with a diverse portfolio, he is now one of the most powerful leaders in modern Chinese history, according to Brown.

To shed more light on Xi’s rise, Brown parses his relationship with his big-shot military father purged by Mao during the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution. Plus, Brown addresses Xi’s business transactions and allegiances, casting a glance at his part in the feud between Deng Xiaoping-age dinosaurs and the new breed of mega-rich “princelings”.

Meantime, while taking a tough line on territorial disputes, the smiling strongman has curbed dissent and blocked some foreign websites. Other sites have been handled through the recruitment of thousands of vigilantes who take down “impure” pages. Still others have been handled by digital guerillas armed with aliases, who plant propaganda.

“Mao fought his battles with real troops on real battlefields. For Xi, the conflict is in virtual space. But the tactics to secure victory – concealment, subterfuge, bluff – are remarkably similar,” writes the shrewd and fluent doctor of Chinese politics with 10-plus books to his name.

Brown is particularly deft at conveying the flavour of party machinations.

“The party is a self-governing empire, and sets its own standards and objectives. In the West, those hunting for sources of power look at parliaments, courts, cabinets, armies and businesses. But there is nothing quite like the autonomy of the party, which is in ultimate control of all these entities. It is the supreme one-stop shop. And that means that as one ascends the hierarchy of the organisation, one gets increasingly giddy with the sort of authority an individual can have,” he writes.

Politburo members can do as they want: they have no terms of reference, no set aims to achieve and no other bodies to answer to, Brown adds, evoking the one that dominates George Orwell’s classic dystopian novel, 1984.

As the Orwellian organisation’s boss, Xi owes his success to that incalculably precious political asset, luck – a knack for being at the right place at the right time – and nous. He is an instinctively good reader of the party’s interests, according to Brown: a King’s College London professor of Chinese studies. With 20 years’ experience of Chinese life, he has worked in education, business and government, including a secretarial stint at the British Embassy in Beijing.

Brown’s diplomatic dimension may explain his deference towards key Xi influence Mao Zedong. Brown describes him as “contradictory and complex” – a generous take, given that Hong Kong-based historian Frank Dikötter has said that, on the genocide front, Mao was 20 times worse than Pol Pot.

Another gripe is the space given to shadowy figures on the party fringes. However hard to get, more personal insight into “the godfather” from wonks and comrades would have been good – sometimes amid a wave of white papers, Xi seems sidelined, even rusticated from the text.

Brown concludes that the future for the peasant emperor is uncertain. Under his guidance, China could become a sustainable, urban, green, high-status entity, according to Brown, who adds that, equally, Xi’s China dream could be killed by a palace coup.

Xi could also be floored by more unrest in Tibet or Xinjiang province in the northwest – or ecological trauma. “An environmental catastrophe, or a pandemic associated with it, is the most likely crisis that could end the Communist regime’s period in power and tear China apart,” Brown writes.

If Xi survives, even prospers, delivering on his programme of a bold, rich, sustainable nation by 2021, when his party role ends the next year, people may want him to stay.

In line, just like power-addicted Russian president Vladimir Putin, Xi may rewrite the constitution – extend his mandate. Not bad for a former manure carrier.