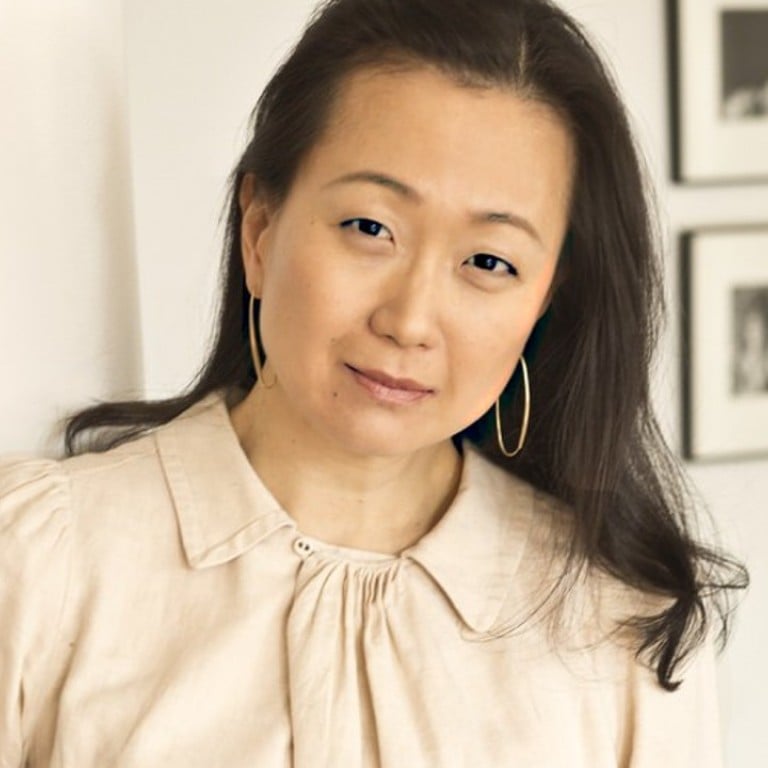

Review | Book review: Min Jin Lee’s Free Food for Millionaires, a modern-day Middlemarch but more fun, gets deserved re-release

Now-acclaimed Korean American author Min Jin Lee’s novel about the social-climbing daughter of immigrants is as relevant in the Trump era as it was when Wall Street millionaires lived high on the hog under George W. Bush

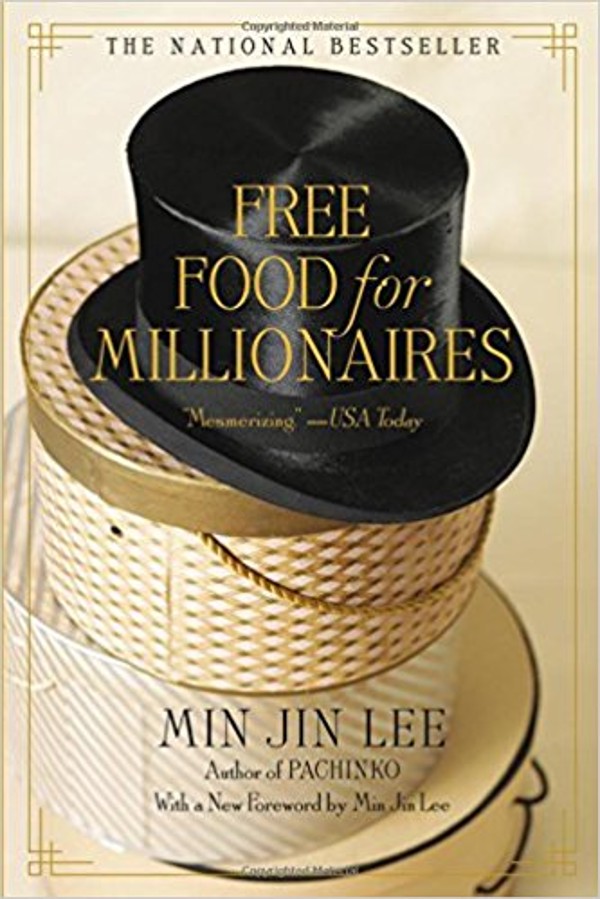

Free Food For Millionaires

by Min Jin Lee

Grand Central Publishing

4/5 stars

As befits a culture obsessed with anniversaries and recycling the not-so-distant past, Lee’s debut has now been re-released with an interesting introduction by the author herself. Here she relives her long, and relatively tortuous journey towards publication, the most important part of which was realising that her own life – a young, ambitious Korean girl growing up in the Queens borough of New York – was a worthy subject for fiction.

Lee’s decade-long apprenticeship culminated in the story of Casey, essentially a young, ambitious Korean girl who had grown up in Queens. Thanks to the tireless efforts of her parents, Joseph and Leah, who run a dry-cleaning business, she studied at Princeton, where she had her first brushes with the high life.

Casey learned what to wear, how to speak and who to date. Her ambitions are embodied by Jay, a clever, but shallow English major who, as the action starts, slaves away as an investment banker at Kearns Davis. Jay is the personification of Casey’s secret American self: his existence and their relationship are utterly unsuspected by Joseph and Leah.

Despite learning valuable lessons in couture and deportment, Casey’s clamber up New York’s slippery pole was never likely to be frictionless: her cultural background and innate volatility ensure that. But two traumatic events sink her choppy progress, and start the tsunami that is Lee’s large, winding novel.

Firstly, she is punched in the face by her father, who feels his suffering in Korea and America has been disrespected by his self-centred daughter, whose fundamental aimlessness he takes as a personal insult. Bruised, distraught and effectively disowned, Casey picks herself up, and heads for the sanctuary of Jay’s Manhattan apartment, only to walk in as he completes the erotic triangle of a ménage à trois. Trauma number two.

Ella is not only Casey’s short-term saviour; she is the second of Lee’s heroines. Raised by her widowed father, Douglas Shim, Ella is denied a mother’s love, but granted material comforts that Casey slowly learns to accept. Ella has her own beau to be, Ted, a Korean from Alaska who treats Ella like a valuable porcelain asset, drives himself to succeed also at Kearns Davis, and finds Casey a job, with a mixture of motives (power, condescension, sexual curiosity) that make you suspect something is not entirely right in his character. And so it eventually proves, but not before he marries Ella and gets her pregnant with a daughter, Irene.

Free Food for Millionaires is ageing remarkably well. The title’s sharp joke is as telling in Trump’s America as it was at the tail end of George W. Bush’s. The millionaire bankers on Kearns Davis’ Asia desk earn a free lunch (a pointed Indian meal, in this instance) after a lucrative deal. If you needed an image for the ever-widening divides separating rich and poor, this is one.

Casey’s leap across this economic chasm is also that of Joseph and Leah who go from Korean poverty to working-class American aspiration. Lee’s thematic acuity is matched by her gifts for dialogue, and creating constant interest with plot hooks that would not be out of place on a box-set binger: infidelity, financial irresponsibility, secret longing, sudden despair, moments of warm-hearted triumph against the odds.

One’s passionate engagement with Lee’s cast owes much to a narrative method that allows constant access to each character’s thoughts within a single scene. The technique is like a film cut that not only shows you another visual point of view, but an existential point of view. Granted, it is a little disorienting, and even overwhelming in the early chapters.

Before Joseph strikes his daughter, we shuttle from Casey’s entitled rage to his entitled self-pity, from his wife Leah’s impotent desolation to Tina’s melancholy resignation. The physical blow is genuinely shocking, and not just for the violence itself. You feel over half a century of unhappy striving (Joseph), two decades of resentment as Casey strives to fulfil her parents’ hopes, which, ironically, only create fresh points of conflict.

Late in the action, Casey finds herself reading George Eliot’s seminal Victorian masterpiece Middlemarch, which exerts an unmistakable influence on Lee’s own story: an epic sweep of economics, medicine, overspending, social mobility, transgression, comedy and tragedy. Lee reconfigures the original material to her own ends.